Partner Institution: University of Warsaw, Institute of Political Science

The System of Local Government in Poland

Andżelika Mirska, University of Warsaw

Types of Local Governments

Poland is a unitary state without any autonomous entities. As a consequence, a uniform system of territorial self-government exists throughout Poland. The traditions of territorial self‑government date back to 1918 when, after 123 years of political oblivion, the Polish state was established. After World War II, Poland was an undemocratic and centralized state which led to, among other things, the liquidation of territorial self-government. The reconstruction of territorial self-government began in Poland with the political transformation after 1989. The first stage was the restoration of territorial self-government in communes (gmina) in 1990, then in 1999 the self-government in counties (powiat) and in voivodeships (województwo) was introduced.

The current Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 1997 introduces two types of territorial self-government, namely local self-government and regional self-government (Article 164). Currently in Poland (since 1999), territorial self-government is three-tier and it is structured as follows:

- self‑government in communes as the basic level of local self-government;

- self-government in counties the second level of local self-government;

- self-government in voivodeships as regional self-government.

In addition, large municipalities (over 100,000 residents) may be granted the status and tasks of a counties (city with powiat rights/cities with powiat status).

Therefore, there are four levels of political representation in Poland: the state and three levels of territorial self-government.

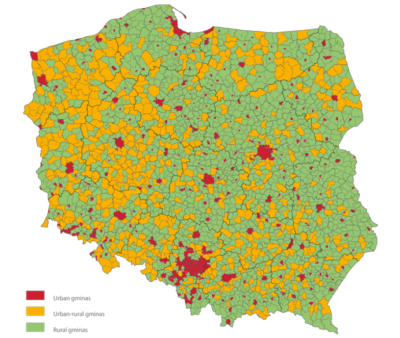

At present (2020), there are 2,477 communes (gmina), including 1,555 rural gminas, 621 urban-rural gminas and 302 urban gminas. The population of gminas ranges from 1.7 million (the Capital City of Warsaw) to 1,300, and the average population of a Polish gmina amounts to 15,000. It means that in the comparison to other European countries, Poland’s gminas are relatively large. If we take into account only urban gminas, the average population is 61,000, whereas in rural gminas the average population amounts to approximately 7,000. At the beginning of the political transformation in Poland in 1990, there were 2,383 gminas. It means that modifications introduced in the division into gminas have been rather minor.

Figure 1: Spatial delimitation of gminas in Poland[1]

Figure 1: Spatial delimitation of gminas in Poland[1]

The second tier of the local government, i.e. the level of counties (powiat), was established in Poland in 1999. At present, there are 314 powiats and 66 cities with powiat status. The population of powiats range from 21,500 to 373,500. The average population of a Polish powiat amounts to 82,000, whereas cities with powiat status have on average 191,000 inhabitants. When the territorial reform was being prepared in 1999, it was the establishment of powiats (as intermediate units between gmina and voivodeship) which gave rise to the greatest controversies. Dissenting voices against the introduction of an additional level of territorial structure (and, in consequence, a local government unit) were not rare. Even now the issue of powiats is under public debate, mainly due to the problem of the financing of powiat local government as well as functional weakness of smaller powiats (Polish powiats are small units in comparison to their counterparts in other European countries). The formation of seven new powiats in 2002 was the last major modification in the map of powiats.

The third level of territorial structure applies to voivodeships (województwo). The voivodeships correspond to the NUTS-2 regions (according to the European Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics),[2] which are the basis for regional operational programs co-financed by the European Union. They year 1999 marked a crucial point in shaping the territory and political system of voivodeships. After lengthy preparations accompanied by political disputes, it was decided to form 16 voivodeships. It meant a departure from territorial fragmentation on a regional level (in the years 1975-1999 there were as many as 49 voivodeships in Poland). As a result of an enlarged territory, voivodeships as regions gained the right to self-government– thus, another stage of decentralization of Poland was reached. So far, the number of voivodeships has not been changed.[3]

Legal Status of Local Governments

The inclusion of the principle of subsidiarity[4] in the preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 1997 and the principle of decentralization[5] in the first chapter of the Constitution is of key importance for the legal status of self-government in Poland. Article 16 provides legal guarantees for local authorities: ‘(i) The inhabitants of the units of basic territorial division shall form a self-governing community in accordance with law. (ii) Local government shall participate in the exercise of public power. The substantial part of public duties which local government is empowered to discharge by statute shall be done in its own name and under its own responsibility.’

A comprehensive regulation concerning territorial self-government is contained in Chapter VII (‘Local government’) of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 1997.

Territorial self-government is based on democratic legitimacy. At each level, residents elect a representative body (the number of councilors currently ranges from 15 to 51, with the exception of Warsaw with 60 councilors). In addition, the head of the executive body (mayor) has been elected directly by the residents at the gmina level since 2002. Moreover, the Constitution of Poland guarantees residents of gminas, powiats and voivodeships the right to directly settle matters through the institution of a local referendum. A referendum on self-taxation of residents for public purposes is a special type of the local referendum. However, such a referendum can only be held at the gmina level.

Local government shall perform public tasks not reserved by the Constitution or statutes to the organs of other public authorities (Article 163 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 1997). Gmina self-government, which has been granted the presumption of competence in matters of territorial self-government, is of fundamental importance. Article 164 establishes the following: ‘(i) The commune (gmina) shall be the basic unit of local government. (ii) Other units of regional and/or local government shall be specified by statute. (iii) The commune shall perform all tasks of local government not reserved to other units of local government.’

Territorial self-government units are subject to the Constitution of the Republic of Poland and the Acts of the Polish State. Three system acts are of fundamental importance:

- the Act of 8 March 1990 on Gmina Self-Government,

- the Act of 5 June 1998 on Powiat Self-Government,

- the Act of 5 June 1998 on Voivodeship Self-Government.

The only criterion of supervision over the activity of self-government is the criterion of legality, supervision is exercised by government administration authorities (the Prime Minister, voivodes[6] and regarding financial matters – regional audit chambers). However, any disputes between the government administration and territorial self-government shall be settled by an administrative court. There are no authoritative interrelations between the tiers of territorial self-government – only voluntary cooperation is possible.

The Constitution divides public tasks performed by self-government into own tasks (financed from the budget of a self-government unit) and commissioned tasks (financed from the state budget).

Gmina self-government performs a wide range of public tasks which include, among others, issues related to local technical infrastructure, social infrastructure, education, health and order protection and safety. In accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, the powiat self‑government ‘assists’ gmina in performing local tasks that exceed the capacity of a gmina (‘supra-communal’ local tasks). While the self-government of gmina and powiat implements a number of public services for local communities on an ongoing basis, the main role of voivodeship self-government is to facilitate economic development of regions. Among other things, the task of the voivodeship self-government is to manage EU structural funds.

(A)Symmetry of the Local Government System

There are three types of gminas:

- urban gminas (their boundaries correspond with the boundaries of the city forming the municipality);

- urban-rural gminas, which include both cities within administrative boundaries and areas outside city boundaries;

- rural gminas without cities within their territory.

Cities in Poland are towns and cities with city rights (granted by the central government). However, it is a formal classification based solely on an administrative criterion. The Act on Gmina Self-Government does not differentiate the tasks of according to this classification – all gminas have the same scope of activity. The exceptions are large urban gminas which also have the status of powiat (city with powiat rights). They carry out the tasks of both gmina and powiat. Currently, there are 66 of them and the general criterion for their establishment is a population over 100,000. However, some local government politicians claim that this threshold should be reduced to 50,000[7].

On the other hand, the need is recognized to merge the cities with the powiat rights and powiats whose authorities are seated in the said cities due to significant disproportions in the institutional potential of powiats. Government analyses indicated a significantly higher potential of cities with powiat rights and a particularly low potential of powiats without large urban centers. The data show that powiats without large cities have significantly scarcer resources allocated to the fulfilment of public tasks of powiats[8].

Public tasks may be performed by individual self-government units independently or by way of cooperation with other self-government units (inter-municipal cooperatives). Self-governments of a given level may cooperate with each other (cooperation between gminas, between powiats, between voivodeships). Moreover, cooperation between the levels is also possible: since 2016, unions of powiats and gminas may be established. The form of the powiat–gmina union is intended for the implementation of tasks that exceed the competence of one tier of self-government. The aim was to enhance the independence and operational flexibility of territorial self-government units. It can also be interpreted as an attempt to address the problems occurring mainly in metropolitan areas.

The legal form of the union of gminas (union of powiats, union of gmina and powiat) requires the establishment of a new legal person to perform part of the tasks of the self-government. Unions of gminas are a very popular form of performing self-government tasks (currently there are 313 of them in Poland and they include from 2 to 49 gminas). There are 7 powiat unions and 8 powiat–gmina unions. Their tasks involve mainly the organization of common local public transport. The same applies to education as only a uniform system of education from primary schools (which is the responsibility of gminas) to secondary schools (which are subject to powiats) can resolve demographic problems or fulfil the expectations of the local labor market.

The performed public tasks may also be modified through ‘delegating’ public tasks by a territorial self-government unit to another territorial self-government unit. This is done by way of a voluntary agreement.

‘Commissioning’ tasks to the self-government by the government administration is a different matter – if they are commissioned by virtue of the law, they are imposed on the self-government ‘from the top’ (together, of course, with financial resources from the Polish state budget). Polish self-governments indicate that those funds are often insufficient.

Political and Social Context in Poland

Compared to other countries, the national political parties are in Poland not very strongly represented at the local government level.[9] To gain a stronger voice, self-governments attempted to create a nationwide political movement of mayors of large cities. For example, in 2011 Union of Mayors – Citizens to the Senate[10] (Unia Prezydentów – Obywatele do Senatu) was established and it put forward its candidates in the elections to the upper house of the Polish Parliament – Senate (majority voting system applies). The Local Government Movement ‘Non-Partisans’ (Ruch Samorządowy ‘Bezpartyjni’) was also established, consisting of mayors and councilors. The purpose of the movement is to be an alternative to political parties in local government elections (primarily at the level of the voivodeship self-government).

However, if we analyze the results of local government elections, the influence of national political parties clearly diminishes, the lower the level of government. Starting from the highest level, i.e. the 16 voivodeship self-governments, it is basically political parties that dominate the elections to the voivodeship assemblies. In the local government elections of 2018, candidates of national parties received a total of 89.4 per cent of votes. The Local Government Movement ‘Non-Partisans’ gained 5.28 per cent of the country’s vote. Regional groupings received marginal support, except for three voivodeships. In the Opolskie Voivodeship, ‘The German Minority Electoral Committee’ traditionally receives strong support (in 2018 – 14.64 per cent). In two other voivodships, regional movements concentrated around local politicians obtained: 8.29 per cent of votes (the Lower Silesian Voivodeship: Electoral Committee of Voters ‘With Dutkiewicz for Lower Silesia’[11]) and 5.26 per cent of votes (the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship: Electoral Committee of Voters ‘Wenta[12]‘s Świętokrzyskie Project’.

At the powiat level, the presence of parties in the elections is weaker, in the 2018 elections the national parties won about 62 per cent of votes. At the level of gminas, the parties have obviously the smallest influence – local election initiatives prevail. In gminas with up to 20,000 inhabitants (single-mandate constituencies) national parties won about 27 per cent of votes. In gminas with over 20 000 inhabitants the figure was approx. 50 per cent.[13] In rural gminas, traditionally, the peasants’ party – the Polish People’s Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe) – has played an important role. In the last elections, the importance of the Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość) has increased, reflecting the situation at the national government level.

The number and share of rural population in the total population of the country is declining. At the end of 2017, the rural population accounted for 39.9 per cent (in 1950 over 63 per cent)[14]. The gminas’ population forecasts of the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) for 2017-2030 indicate, above all, a strong development of major urban agglomerations with adjacent areas. They will continue to attract people from more peripheral areas. At the same time, a continuation of the suburbanization process should be expected, which will lead to a significant increase in population in the gminas adjacent to big cities.[15] These changes are caused by lower prices of flats or house building costs and reflect the growing economic status which enables inhabitants to move to an area more beneficial in terms of being a ‘greener environment’.[16] In 2018, 55 cities with powiat rights (there are 66 cities of this type in total) recorded a decrease in population compared to the previous year. These included cities that aspire to play the role of a metropolis (Poznań, Łódź, Bydgoszcz). Warsaw, the capital city of Poland recorded an increase. The number of gminas with less than 5,000 inhabitants is steadily growing. There are already approx. 800 of them.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

The Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2 April 1997 <https://www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/angielski/kon1.htm>

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Biegańska J, ‘Rural Areas in Poland from a Demographic Perspective’ (2013) 20 Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series 7

Committee on the Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Member States of the European Charter of Local Self-Government (Monitoring Committee), ‘Local and Regional Democracy in Poland’ (Report CG36(2019)13 final, Congress of Local and Regional Authorities 2019) <https://rm.coe.int/local-and-regional-democracy-in-poland-monitoring-committee-rapporteur/1680939003>

Jurgilewicz O, ‘The Importance of Local Government in Poland – General Issues’ (2015) 22 Humanities and Social Sciences 47

Kulesza M and Sześciło D, ‘Local Government in Poland’ in Angel-Manuel Moreno (ed), Local Government in the Member States of the European Union: A Comparative Legal Perspective (INAP 2012)

Levitas A, ‘Local Government Reform as State Building: What the Polish Case Says About “Decentralisation”’ (2018) 45 Zarządzanie Publiczne/Public Governance 5

Mirska A, ‘State policy on the formation and modernisation of Polish territorial structure’ in Europäisches Zentrum für Föderalismus-Forschung Tübingen EZFF (ed), Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2018: Föderalismus, Subsidiarität und Regionen in Europa (Nomos 2018)

Regulski J, ‘Local Government Reform in Poland: An Insider’s Story’ (Local Government and Public Service Reform Initiative 2003) <http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/untc/unpan012822.pdf>

Sulowski S (ed), The Political System of Poland (Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa 2007)

Local Responsibilities and Public Services in Poland: An Introduction

Andżelika Mirska, University of Warsaw

The Polish local self-government provides mainly a wide range of public services. Decentralization was a fundamental element of the Polish transformation and is a fundamental principle of the Polish political system. The self-government is responsible for satisfying the needs of the residents on an ongoing basis, including taking care of safety and public order. These tasks are allocated in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity. For example, as regards road maintenance: certain roads are the responsibility of the gmina, others of the powiat, then there are regional roads and finally roads for which the Polish State assumes responsibility. The same applies to tasks related to education, health care and social care. Moreover, it is very common to delegate state tasks to be performed by self-governments (so that they are performed as close to the citizens as possible).

In the years 1990-1999, there was a simple scheme of performing public tasks in Poland: responsibility was taken over either by the gmina self-government or by the Polish state (bodies and offices of delegated government administration). However, during political transformation further decentralization was given priority, so works on support for gminas in performing local tasks were in progress. In 1999, the powiat self-government was established (which includes several gminas in its territory). The powiat, as a larger self-government unit, took over the local tasks of a higher level (e.g. the gmina is responsible for primary schools, while the powiat is responsible for secondary schools). The number of gminas in one powiat ranges from 3 to 19.[1]

The exceptions are large urban gminas which due to their population and financial potential are able to handle higher-level tasks. They were granted the status of cities with powiat rights (one urban gmina (one city) corresponds to one powiat).

Therefore, gmina and powiat complement each other in order to provide services to the residents on an ongoing basis. However, the voivodeship self-government, established in 1999, is to play the role of a regional self-government, which has assumed some of the responsibility for the economic development of the regions from the state.

From the legal point of view, self-government units are to perform public tasks on their own behalf and on their own responsibility. Importantly, the law does not distinguish categories of tasks for urban or rural gminas. Self-governments may carry out these tasks independently, entrusting tasks to other self-governments, cooperating with other self-governments. They can also privatize tasks or use the instrument of a public-private partnership.

As far as cooperation in performing tasks is concerned, there are 313 inter-communal unions in Poland. Common waste management is very popular – there are 70 such communal unions. The largest union consists of 27 gminas. In total, 683 gminas are members of a union whose objective is the common waste management, which accounts for 27.5 per cent of gminas in Poland[2].

Another practice is to delegate local government tasks to other entities. The differences in operating strategies between urban and rural gminas can also be observed in this area.

A gmina self-government may assign the management of a small school (up to 70 students) under an agreement to a legal entity that is not a self-government unit (e.g. an association, a foundation) or to a natural person. This solution protects small rural communities against the liquidation of schools.

Tasks may be also carried out under a public-private partnership (e.g. running a sewage treatment plant (Konstancin-Jeziorna, Osina), building a local road (Łazy), building a school and a sports hall (Piastów)).

In Poland, PPPs are established very carefully. In the history of Poland, 135 such partnerships have been recorded to date. The majority of the partnerships involve gminas which entered into 84 such agreements in total (urban gminas 39, rural gminas 25, urban and rural gminas 20). However, due to the fact that some gminas entered into more than one partnership, only 57 gminas in Poland have experience with such a form of public service provision. It accounts for 2.3 per cent of all gminas[3].

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

The Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2 April 1997 <https://www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/angielski/kon1.htm>

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Szymańska D and Biegańska J, ‘Infrastructure’s and Housing’s Development in the Rural Areas in Poland – Some Problems’ (2012) 4 Journal of Infrastructure Development 1

Zyzda B, ‘Selected Issues Concerning Public Tasks of the Communes in Poland and Germany’ (2017) 7 Wroclaw Review of Law, Administration & Economics 30

[1] Rady Ministrów, ‘Obwieszczenie Prezesa Rady Ministrów z dnia 23 sierpnia 2017 r. w sprawie wykazu gmin i powiatów wchodzących w skład województw’ (ISAP M.P. 2017 poz. 853, 7 September 2017) <http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WMP20170000853> accessed 1 July 2019.

[2] Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration, ‘Zarejestruj, zmień statut lub wyrejestruj związek międzygminny, związek powiatów, związek powiatowo-gminny’ (Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, 2 July 2019) <https://www.gov.pl/web/mswia/zarejestruj-zmien-statut-lub-wyrejestruj-zwiazek-miedzygminny-zwiazek-powiatow-zwiazek-powiatowo-gminny> accessed 10 July 2019.

[3] ‘Bazy projektów PPP’ (Platforma Partnerstwa Publiczno-Prywatnego, 7 August 2019) <http://www.ppp.gov.pl/baza/Strony/baza_projektow_ppp.aspx> accessed 4 July 2019.

Local Financial Arrangements in Poland: An Introduction

Andżelika Mirska, University of Warsaw

Legal Basis

The issue of financing the activities of local government in Poland was addressed in Article 167 of the Polish Constitution: ‘Units of local government shall be assured public funds adequate for the performance of the duties assigned to them. Alterations to the scope of duties and authorities of units of local government shall be made in conjunction with appropriate alterations to their share of public revenues. The revenues of units of local government shall consist of their own revenues as well as general subvention and specific (targeted) grants from the State Budget of Poland. The sources of revenues for units of local government shall be specified by act.’

Since the reactivation of local government in 1990, the fourth act in this respect has been in force. Currently, it is the Act of 13 November 2003 on the Revenues of Local Government Units. It introduces a separate system of financing of gminas [communes, municipalities] (including cities with powiat rights), powiats [counties], voivodships and regulates the mechanism for the elimination of income disparities between local government units.

General Structure of Public Finances

In Poland, the ratio of revenues and expenditures of local governments (gmina, powiat and voivodeship self-governments) to GDP is fairly high. In 2018, the revenue of all local government units calculated according to the methodology adopted by the European Union amounted to PLN 251.8 billion, which corresponded to 11.9 per cent of GDP (in 2008 – 13.9 per cent, in 2015 – 12.7 per cent, in 2016 – 11.5 per cent, in 2017 – 11.6 per cent)[1]. This clear downward trend in the years 2008-2017 was primarily attributable to the effects of the global economic crisis. The Polish local government sub-sector is also characterized by an expenditure-to-GDP ratio higher than the EU average. Again, there is a downward trend in the value of the ratio (from 14.1 per cent in 2009 to 12.7 per cent in 2015).[2]

In comparison to other EU countries, in Poland the ratio of local government units’ revenues to GDP is higher than the EU average. Out of the 21 EU unitary states with a significant range of local government activities[3], Poland ranks sixth in terms of local government’s revenues in relation to GDP. However, this does not mean that public finances in Poland have been decentralized. Despite relatively high income of the local government, it is still mostly derived from the transfer of funds from the Polish state budget.[4]

The financial situation of local government units varies depending on the type of local government (gmina, powiat or voivodship). Cities with powiat rights take a special position. In addition, we observe spatial diversity in the prosperity of gminas attributed to local conditions (e.g. the location of industrial plants which pay part of CIT to gminas‘ budgets). The financial situation of the local government in Poland is also significantly influenced by access to financial resources from the European Union. At present, the financial condition of local governments is strongly affected by the state policy in terms of determining tasks and public finances. Moreover, changes in the financial situation of local governments in metropolitan areas (regions) may be observed.

Revenue Structure of Local Government

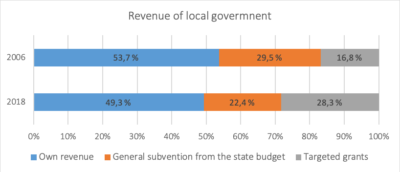

Figure 2: Structure of local government revenue (gmina, powiat and voivodship) in 2006 and 2018.

The largest category in the structure of revenue of local governments in Poland is own revenues which in 2018 constituted 49.3 per cent of total revenues. The remaining funds are transferred from the state budget: the share of general subvention in the revenue of the local government amounted to 22.4 per cent, while targeted grants – 28.3 per cent.[5]

In the structure of own revenue of local government units, in 2018, the largest share was represented by income from the share in personal income tax (PIT) revenues – 41.0 per cent, property tax – 18.2 per cent, from the share in corporate income tax (CIT) revenues – 7.8 per cent.

Local government units in Poland are, next to enterprises, the most important category of beneficiaries of funds from the European Union. In 2007-2013, approximately 25 per cent of all funds from the EU budget allocated to Poland were used by local governments.[6] In 2018, EU funds constituted 6.7 per cent of total revenue of local government (they are classified as subsidies). In relation to the total revenue of particular types of local government units, income from the EU constituted: in gminas – 5.1 per cent, in cities with powiat rights – 5.0 per cent, in powiats – 6.4 per cent, in voivodships – 26.9 per cent. It should be emphasized that the absorption capacity of local government remains in close correlation with the financial standing and state of local finances.

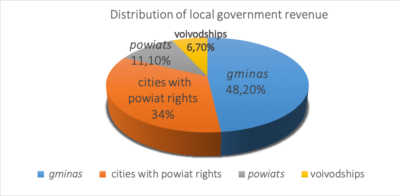

Figure 3: Distribution of local government revenue among gminas, cities with powiat rights, powiats and voivodeships.

Figure 3: Distribution of local government revenue among gminas, cities with powiat rights, powiats and voivodeships.

In the structure of revenue of all three tiers of local government (gminas, powiats and voivodships), the highest income is allocated to the first tier of local government, i.e. gminas and cities with powiat rights – 82.2 per cent in total[7].

Gminas and cities with powiat rights are and will continue to be the key to achieving such objectives as equalizing the standard of living in different regions of Poland and creating conditions for local development. For this reason, the next part of the study will examine the basic level of local government in Poland, i.e. the financial situation of gminas (including cities with powiat rights).

Structure of Gminas’ Revenue

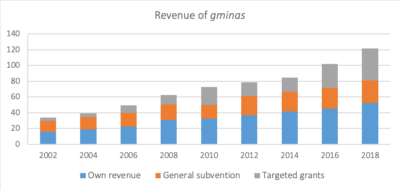

The changes in the state of the gmina’s finances indicate that the revenue of gminas is increasing annually, in 2018 it reached the level of PLN 121.4 billion. Compared to 2002, when the total revenue of gminas amounted to PLN 37.3 billion, this means an increase of 225 per cent over 16 years.

Figure 4: Revenue of gminas 2002-2018.

Figure 4: Revenue of gminas 2002-2018.

The 2018 revenue structure of all gminas and cities with powiat rights was as follows: own revenues 43.2 per cent, general subvention 23.4 per cent, targeted grants for commissioned tasks – 33.4 per cent.

If we divide gminas into rural gminas, urban and rural gminas, urban gminas and separately cities with powiat rights, the following picture emerges.

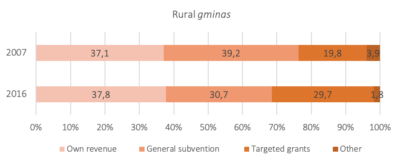

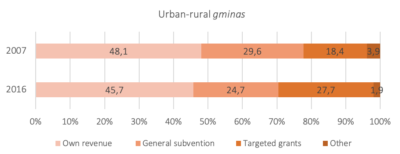

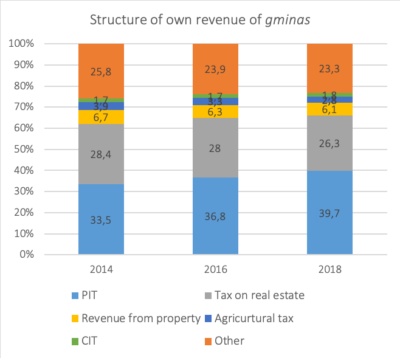

Figure 5: Structure of revenue of gminas (rural, urban-rural and urban) in 2007 and 2016.

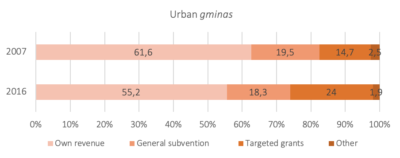

Figure 6: Structure of revenue of cities with powiat rights in 2007 and 2016.

The general trend concerning the sources of financing of gminas suggests an increase in financial transfers from the state budget. In particular, the amount of targeted grants related to the social policy of the state has increased (e.g. the government program ‘Family 500 plus’, introduced on 1 April 2016, which involves financial benefits for families with children). In 2018, the grant for the ‘Family 500 plus’ program accounted for 13.8 per cent of the gminas‘ revenue (targeted grants in total constituted 24 per cent of the gminas‘ revenue).

The second noticeable tendency is greater dependence of rural gminas on financial transfers from the state budget. It pertains to general subvention intended to support gminas with low own revenue. Its purpose is to eliminate disproportions in the distribution of own revenue of the local government.

Categories of Gminas‘ own Revenue

Gminas‘ own revenue includes: local taxes (mainly: agricultural tax, forestry tax, tax on real estate, tax on means of transport). Gminas enjoy financial autonomy in this respect – they can set tax rates on their territory (within the limits set by law). Additionally, a part of the income from PIT[8] and CIT[9] is transferred to the gmina’s budget. PIT and tax on real estate are of fundamental importance in financing the gmina’s budget. The basis for taxation of real estate in Poland is its area and not its value. This has been a matter of dispute – the proposal to introduce a real estate cadaster and a cadastral tax has long been under discussion.

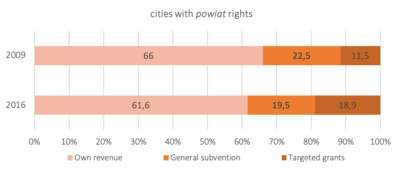

Figure 7: Structure of own revenue of gminas.

Figure 7: Structure of own revenue of gminas.

The main problem in the area of gmina’s revenue from PIT is the introduction of a number of tax reliefs in recent years which cause a decrease in the gmina‘s income from this source. These are decisions taken by the government and the parliament – without the participation of gminas. This causes great dissatisfaction and protests of local governments.

General Subvention for Gminas

A general subvention is a form of non-refundable financing of the local government budgets by the state budget. These are funds transferred to equalize the level of own revenue of local governments. The subvention is an instrument for eliminating income disparities between local governments. The funds from the subvention may be disbursed by the local authorities at their own discretion.

The general subvention for gminas consists of three parts: education, compensatory and offsetting part. In 2019, the educational part (for running schools) accounted for 77.2 per cent of the total subvention. One of the factors used for the determination of the compensatory part (apart from the amount of tax revenue per capita) is the population density in a gmina which is lower than the Polish average. It is an aid for rural gminas – sparsely populated.

The funds which are transferred to poorer gminas in the form of a general subvention are derived from the state budget but also from payments made by wealthy gminas with high income from local taxes. Such a system of redistribution of gminas’ revenue has been objected by wealthy gminas for a long time. In 2011, a citizen bill (‘citizens’ legislative initiative’)[10] was prepared the aim of which was to reduce the amount of payments made by wealthy gminas to the general subvention. The bill was not seconded in parliament. In 2018, 88 gminas made payments to the state budget for the benefit of poorer ones (in Poland there are 2477 gminas in total). This means that 3.5 per cent of gminas in Poland participate in the system of co-financing poorer gminas.[11]

The subvention is certainly a more predictable source of finance than other types of own revenue which are tax-related and thus largely determined by the dynamics of economic growth. During the economic slowdown, the general subvention is therefore intended to stabilize the income situation of the local government. However, its critics claim that the general subvention decreases the motivation of the gmina’s self-government to rationalize expenditures.

Targeted Grants for Gminas

Targeted grants are granted gminas from the state budget for the execution of additional tasks (unused grants must be returned to the budget). Local government units do not have any actual influence on the grant amount. For several years, local governments have been suggesting that targeted grants are insufficient to fulfil the commissioned tasks. As a result, in order to ensure the performance of these tasks, local governments finance them from their own resources.

In recent years, the local governments of large cities have decided to file claims in civil courts against the Polish State Treasury for payment of the missing funds for the performance of commissioned tasks (the funds are primarily needed for the tasks related to keeping population registers, issuing identity cards, adjudicating in registration cases and keeping vital records). These are long and costly proceedings, however, more and more large cities are deciding to go to court. The precursor of such an action was Cracow[12] which after 5 years obtained a court judgement ordering the Polish State Treasury to return the funds that Cracow allocated for co-financing of commissioned tasks.[13] The increasing number of court cases may possibly result in a change in the methods of determining the costs of tasks commissioned by the Polish Government and Parliament.

Expenses of Gminas

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in local government expenditure, both in the group of current and capital expenditure.[14] On the one hand, it results from an increase in the scope of tasks and the realization of local government investments, however, on the other hand, it is an effect of a significant increase in the costs of performing public tasks.

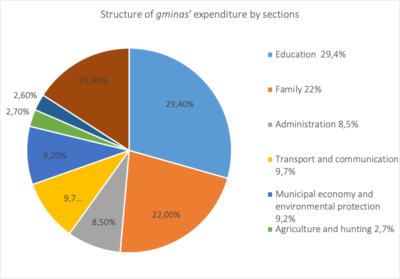

The most important items of the gminas’ expenditure include ‘education and upbringing’ and ‘family’ – in total they constitute over half of the gminas’ budget expenditure (51.4 per cent). The budget of gminas also disburses funds for agriculture and hunting – 2.7 per cent. Compared to 2017, expenditure on agriculture and hunting increased by 48.8 per cent. It resulted from, inter alia, the implementation of the sub-measure ‘Support for investments in agricultural holdings’ under the Rural Development Program for 2014-2020 financed from the EU.

Figure 8: Gminas’ expenditure.

Figure 8: Gminas’ expenditure.

Salaries for employees, including teachers (approx. 34 per cent of gmina’s expenditure) constitute a relatively considerable part of expenditures. Considering that between 2015 and 2018 salaries in the local government increased by 15.8 per cent, this places a heavy burden on the local government budget. This is a particularly difficult problem for small rural gminas which experience financial difficulties and propose that the financing of teachers’ salaries should be assumed by the Polish state.

Capital Expenditures of Gminas

The main determinant of the state of local government finances, related to its role in the development policy, is the investments made. The increase in PIT revenues contributed to the achievement of an operating surplus[15] in 2018 in the local government budgets which was entirely allocated to development – i.e. investments. It was also possible thanks to subsidies of 21.5 billion from the European Union and incurring new liabilities (mainly loans) for a total amount of approx. PLN 16.2 billion. Even more investments were planned for 2019.

Investment priorities have evolved over the years. In the 1990s particular importance was attached to the provision of telecommunications infrastructure and development of gas network. Then there was the period of water supply and sewage investments. For some time, transport investments, including road and purchase of rolling stock have been high in the hierarchy of needs. However for over a decade, more and more local governments have been focusing on cultural, sporting and recreational activities.[16]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Jarosiński K, Maśloch G, Opałka B and Grzymała Z, Financing and Management of Public Sector Investments on Local and Regional Levels (PWN SA 2015)

Galiński P, ‘Determinants of Debt Limits in Local Governments: Case of Poland’ (2013) 213 Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 376

[1] All statistical data prepared by the author on the basis of official documents of state authorities: Annual ‘State Budget Execution Analysis’ prepared by the Supreme Audit Office, <https://www.nik.gov.pl/kontrole/analiza-budzetu-panstwa >; Annual reports of the Statistics Poland (the Central Statistical Office), ‘Financial Economy of Local Government Units’, <https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/national-accounts/general-government-statistics/financial-economy-of-local-government-units-2018,2,15.html >; Annual reports of the Ministry of Finance, <https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/sprawozdania-roczne > and Annual reports of Regional Accounting Chambers, <https://www.rio.gov.pl/modules.php?op=modload&name=HTML&file=index&page=publ_sprawozdania> accessed 1 December 2019.

[2] Poniatowicz Marzanna, ‘Stabilność finansowa jednostek samorządu terytorialnego w aspekcie nowej perspektywy finansowej Unii Europejskiej i zmian w systemie dochodów samorządowych’ (2016) 125 Ekonomiczne Problemy Usług 7 <https://wnus.edu.pl/epu/file/article/view/2740.pdf > accessed 1 December 2019.

[3] Excluding Cyprus, Malta and Luxembourg, where the scope of local government activity is fairly limited.

[4] College of the Supreme Audit Office, ‘Analysis of State Budget Execution and Monetary Policy Objectives in 2015’ (Supreme Audit Office 2016) 260 <https://www.nik.gov.pl/plik/id,11415,vp,13764.pdf> accessed 1 December 2019.

[5] Mirosław Błażej and others, ‘Financial Economy of Local Government Units 2018’ (Statistics Poland 2019) 33 <https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rachunki-narodowe/statystyka-sektora-instytucji-rzadowych-i-samorzadowych/gospodarka-finansowa-jednostek-samorzadu-terytorialnego-2018,5,15.html> accessed 1 December 2019.

[6] Patrycja Chrzanowska, ‘Wykorzystanie funduszy europejskich przez samorządy terytorialne w kontekście rozwoju ekonomiczno-gospodarczego gminy [Use of European Funds by Local Authorities in Economic Development Context’ (2015) 106 Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczo-Humanistycznego w Siedlcach 23 <https://repozytorium.uph.edu.pl/bitstream/handle/11331/535/Chrzanowska.P_Wykorzystanie_funduszy_europejskich_przez_samorzady_terytorialne.pdf?sequence=1 > accessed 15 October 2020.

[7] Ministry of Finance, ‘Report on the Execution of the State Budget for the Period from 1 January to 31 December 2018. Information on the Execution of Budgets of Local Government Units’ (Council of Ministers 2019) 11 <https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/zestawienia-zbiorcze > accessed 2 November 2019.

[8] Revenue from PIT contributes towards the budgets of gminas (39.34%), powiat budgets (10.25%), voivodship budgets (1.60%) and the state budget (49.81%).

[9] Revenue from CIT contributes towards the budgets of gminas (6.71%), powiat budgets (1.4%), voivodship budgets (14.75%) and state budget (77.14%).

[10] The right to submit a bill is granted in Poland to a group of at least 100 000 citizens having the right to vote in elections to the Sejm (Art 118(2) of the Polish Constitution 1997).

[11]A similar mechanism of revenues redistribution applies at the level of powiats and voivodeships.

[12] Cracow (Kraków) – the second largest city in Poland.

[13] Weber Maria, ‘Miasta w sądzie walczą o pieniądze z rządem [Cities fight in court with the government for money]’ (Rzeczpospolita, 22 October 2019) <https://regiony.rp.pl/prawo/22244-zadania-trafiaja-do-sadu > accessed 1 December 2019.

[14] In the structure of gminas‘ expenditures in 2018, current expenditures constituted 79.4% whereas capital expenditures 20.6%. If we consider rural gminas separately, current expenditure amounts to 78.3% and capital expenditure to 21.7%.

[15] The operating surplus is the positive difference between current revenue and current expenditure. Accordingly, the negative result between current revenue and current expenditure represents an operating deficit.

[16] Swianiewicz Paweł and Łukomska Julita, ‘Liderzy inwestycji. Ranking wydatków inwestycyjnych samorządów 2015-2017’ (Wspólnota, 20 January 2020) <https://www.wspolnota.org.pl/fileadmin/user_upload/Andrzej/11_2017/Nr_19_Ranking_-_Wydatki_inwestycyjne_2015-2017.pdf > accessed 2 November 2019.

The Structure of Local Government in Poland: An Introduction

Andżelika Mirska, University of Warsaw

The number of local government units in Poland is relatively stable. As far as the number of gminas [communes, municipalities] is concerned, there were 2,383 at the time of the restoration of local government in 1990. Currently, there are 2,477 of them. This means an increase in the number of gminas by 3.9 per cent. Between 1990 and 2018, the number of gminas with less than 2,000 inhabitants increased from 15 to 40, while the number of gminas with less than 5,000 inhabitants increased from 654 to 794[1]. The number of cities with powiat rights remains unchanged and currently stands at 66.

The number of powiats [counties], that were established in 1999 was 308, currently there are 314. The structure of voivodeships (16 units) did not change.

However, this does not mean that the problem of the territorial structure in Poland does not provoke disputes and political discussion. On the one hand, local communities are active and take initiatives to establish separate smaller territorial units. On the other hand, the central government, which has authority to introduce changes in the territorial structure of the country, proposes solutions aimed at consolidating small gminas and powiats. Moreover, a discussion is taking place among experts about dysfunctions in the territorial division and the desirable changes. The discussion about metropolitanization processes is especially important. It entails the determination of the development strategy for Poland (polarization-diffusion model versus sustainable development model)[2].

Thus, territorial units in Poland have not been consolidated, which has been a dominant trend in the last few decades in European countries (e.g. Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, the Netherlands).

The numerous causes for the process opposite to consolidation, i.e. fragmentation of the gmina structure in Poland, include inter alia:

- the establishment of new gminas was a manifestation of grassroots social movements in the process of democratization and restoration of self-government after 1990. Local government in localities was often considered an important value;

- the lack of statutory provisions on the criteria for the establishment of new gminas resulted in spontaneous and uncontrolled division.

It was only in 2015 that a legal provision was introduced to counteract the fragmentation of the territorial structure in Poland. The criterion of gmina revenue and population size was adopted.

The above provision prohibits the establishment of gminas in which:

- the revenue would be lower than the lowest tax revenues per capita provided for individual gminas in the Act of 13 November 2003 on Revenue of Local Government Units;

- the population of the newly established gmina would be lower than that in the gmina with the smallest population in Poland.[3]

On the other hand, incentives for voluntary mergers of gminas and powiats are offered. They include financial incentives which were first introduced in Poland in 2003. Gmina or powiat established as a result of voluntary consolidation is provided with additional funds from the state budget for 5 years (increased share in PIT revenues for a new gmina or powiat).[4] Even so, there had not been a single consolidation of territorial units in Poland until 2015.[5] For this reason, the financial incentive was increased in 2015. The first voluntary merger took place in 2015. Two territorial units were consolidated: the city with powiat rights (Zielona Góra) was merged with the surrounding rural gmina (under the same name: Zielona Góra). The initiative was undertaken by the city which conducted an intensive promotional campaign for the merger. The authorities of the rural gmina were rather reluctant and sceptical. Eventually, in a local referendum, which took place only in the rural gmina, 53.4 per cent of the inhabitants voted in favor of the merger. Accordingly, the Polish government decided to merge the two gminas. As a result, Zielona Góra (city with powiat rights) increased its area from 58.34 sq m to 278.79 sq m, becoming the sixth largest city in Poland. The population has increased by about 20,000 and is now 140,000 inhabitants.

The financial incentives are crucial in joining local government units on the example of Zielona Góra issue. What is more, residents of the village were allowed by the authorities of Zielona Góra to decide (during the village meetings) about the allocation of additional funds from the state budget on the investments. As announced by the Mayor of Zielona Góra, the money was divided among the village councils in proportion to the number of individual villages’ residents. The infrastructure investment extending and the areas increase intended for investment were the most expected benefits during the information campaign for the connection of the City of Zielona Góra and the rural Commune of Zielona Góra. Conversely, the local taxes raise and the cost of living increases for rural areas residents could be the main threats to the rural communities.[6]

All adjustments to the territorial structure of gminas, powiats and voivodships are made by the central government in Poland. It is mandatory for the government to consult the local authorities affected by these changes. Both representative bodies and residents are consulted (a local referendum may be carried out). However, the outcome of the consultations is not binding on the government. The residents also have the right to take the initiative to establish, merge, divide and liquidate a gmina and establish the borders of the territorial unit. It is implemented in the form of a local referendum.

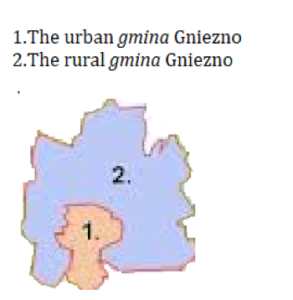

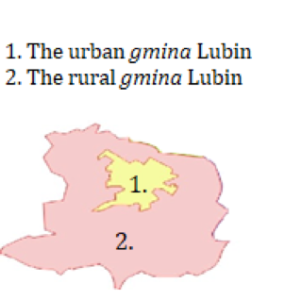

As regard the aforementioned issue of consolidation of territorial units, the above example of Zielona Góra draws attention to a wider problem of territorial structure in Poland, namely the so-called ‘bagel’-gminas [gminy obwarzankowe] (Figure below). This means that in the vicinity of a rural gmina there is a separate city (urban gmina or city with powiat rights) – often with the same name. As there is no administrative center in a rural gmina, the authorities and administration of that rural gmina are based in a neighboring city (which is a separate gmina with its own authorities and administration). It is often the case that the rural and municipal authorities are based in the same building.

Figure 9: Examples of the shape of ‘bagel’-gminas..[7]

In Poland there are 144 urban gminas (and 14 cities with powiat rights) surrounded by rural gminas –‘bagels’. According to some experts, a systemic solution is needed – i.e. a merger of all ‘bagel’-gminas with cities. The authorities of individual cities and the Association of Polish Cities (Związek Miast Polskich) also propose such a solution.[8] They claim that the inhabitants move from the city to the suburbs, i.e. to the area of the rural gmina (where they also pay PIT which contributes towards the budget of the rural gmina), and work in the city and use the local infrastructure (the free-rider problem). It is also argued that cities need land for urban investments. However, the ‘bagel’-gminas are reluctant to hold negotiations about consolidation with the city and are concerned about a loss of identity, independence and, of course, financial independence. It is argued that the indebted cities want to repair their finances through a merger with a rural gminas (bonus from the central budget). The 2013 report of the Minister of Administration and Digitization states that the government does not plan systemic solutions and top-down liquidation of all the ‘bagel’ gminas but only expects voluntary mergers.[9]

In recent years, the conflict between urban and rural gminas in Poland has been aggravating. Cities are attempting to take over some of the rural areas (officially: adjustment of borders between territorial units). The parties to the conflict are represented by local government organizations: the Association of Rural Communes (Związek Gmin Wiejskich) and Association of Polish Cities. Both parties present conflicting demands and they seek to win over the Polish government. Rural gminas demand a guarantee of inviolability of their borders,[10] while cities postulate that the government should issue permits to increase their area at the expense of neighboring gminas, as they need land for investments.[11] In each case, the government decides on the adjustment of the borders between the territorial units – considering the requests of the cities to take over a part of the area of the neighboring gmina.

Since the territorial reform of 1999, metropolitan areas have not been regulated. The government proposed various top-down solutions – however, none of them eventually was adopted. The dispute concerned, among other things, the question of which cities in Poland can be considered as ‘metropolises’. Government documents from 2011 referred to 10 metropolitan areas, identified on the basis of a number of criteria, including the population over 30 000.[12] However, no new territorial units have been created. The progress was made in 2017, when the first metropolitan territorial unit in Poland was established. Under an act, the Upper Silesian and Zagłębie Metropolis [Górnośląsko-Zagłębiowska Metropolia], i.e. the metropolitan union for the metropolitan area of the Upper Silesian conurbation, was established. To date, no other metropolitan union has been established by a top-down decision.

For years, however, very large cities with their surrounding gminas and powiats have been establishing grassroots associations and arrangements to jointly carry out tasks in functional areas (e.g. a joint metropolitan ticket for public transport).

Examples of voluntary cooperation in the functional areas of the largest cities in Poland include:

- Gdańsk-Gdynia-Sopot Metropolitan Area[13] (2011), an association of 57 local governments, an area of 5.500 sq km with 1.5 million inhabitants;

- Metropolis of Poznań[14] (2007), an association of 23 local governments, 3,000 sq km, 1 million inhabitants.

However, this was not a common practice in large Polish cities. One method of encouraging or even forcing cooperation between large cities and their functional areas involved a financial incentive from the European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Fund. It involves an instrument implemented in Poland to support cities, namely the Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI). Large cities and surrounding gminas, in order to cooperate under the ITI model, establish a partnership (e.g. an association or an inter-gmina union) or enter into an agreement and prepare a joint ITI strategy. It should include objectives and projects to be implemented.

Thus, the largest cities were ‘forced’ to cooperate in exchange for additional funding. This resulted in the cooperation between local governments, e.g.

- Cracow Metropolis[15] (2014), 15 local governments, 1.2 million inhabitants, 1,275 sq m;

- Warsaw Functional Area[16] (2014), Warsaw and 39 gminas surrounding Warsaw, 2.7 million inhabitants, area of 2,932 sq km.

Moreover, the EU funds allow the implementation of cross-border cooperation programs. These programs are open to participation, alongside other entities, of cross-border local governments from Poland and neighboring countries. Programs carried out currently (2014-2020): ‘Poland-Slovakia’, ‘Poland-Czech Republic’, ‘Poland-Saxony’, ‘Poland-Brandenburg’, ‘Poland-Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania-Brandenburg’, ‘Poland-Lithuania’, ‘Poland-Belarus-Ukraine’, ‘Poland-Russia’, ‘South Baltic’ (Denmark, Lithuania, Germany, Poland and Sweden), ‘Baltic Sea Region’ (Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, selected regions of North-East Germany, non-EU countries): Norway, Belarus, Russia).[17]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Kaczmarek T, ‘Functional Urban Areas as the Focus of Development Policy in Poland’ (2015) 29 Rozwój Regionalny i Polityka Regionalna 9 <http://obserwatorium.miasta.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/RR29_009-019.pdf>

Swianiewicz P, ‘If Territorial Fragmentation is a Problem, is Amalgamation a Solution? An East European Perspective’ (2010) 36 Local Government Studies 183 <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03003930903560547>

Mirska A, ‘State policy on the formation and modernisation of Polish territorial structure’ in Europäisches Zentrum für Föderalismus-Forschung Tübingen EZFF (ed), Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2018: Föderalismus, Subsidiarität und Regionen in Europa (Nomos 2018)

[1] Katarzyna Ciesielska, Ewa Kacperczyk, Krystyna Korczak-Żydaczewska and Mirosława Zagrodzka, ‘Demographic Yearbook of Poland’ (Statistics Poland 2019) <https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/powierzchnia-i-ludnosc-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-w-2019-roku,7,16.html> accessed 22 November 2019.

[2] Andżelika Mirska, ‘Probleme der Metropolisierung in Polen in Hinblick auf die territoriale Struktur des Landes ‘ in Europäisches Zentrum für Föderalismus-Forschung Tübingen EZFF (ed), Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2013: Föderalismus, Subsidiarität und Regionen in Europa (Nomos 2013).

[3] Art 4(d) of the Act of 8 March 1990 on Gmina Self-Government.

[4] Art 41 of the Act of 13 November 2003 on the Revenues of Local Government Units.

[5] The response of the Ministry of Administration and Digitization to parliamentary question no 24063 on the consequences of administrative reform, <http://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm7.nsf/InterpelacjaTresc.xsp?key=0F92DD9D > accessed 22 November 2019.

[6] Piotr Dubicki and Piotr Kułyk, ‘Proces integracji miasta z gminą wiejską. Przykład Zielonej Góry. The Process of Urban-Rural Integration. Using the Example of Zielona góra’ (2018) 32 Studia Miejskie 113 <http://www.studiamiejskie.uni.opole.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/S_Miejskie_32_2018-Dubicki.pdf>.

[7] Source: own elaboration based on Association of Volunteer Firefighting Brigades, ‘Lista stron OSP’ (Związek Ochotniczych Straży Pożarnych RP, 2008) <https://www.osp.org.pl/hosting/katalog.php?id_w=16&id_p=309&id_g=2281 > accessed 2 November 2019.

[8] Tomasz Żółciak, ‘Cicha wojna na linii gminy – miasta o zmiany granic [Silent War Between Rural Gminas and Cities for Changes of Borders]’ (GazetaPrawna.pl, 31 January 2018) <https://serwisy.gazetaprawna.pl/samorzad/artykuly/1101214,wojna-na-linii-gminy-miasta-o-zmiany-granic.html> accessed 22 November 2019.

[9] Ministry of Administration and Digitization, ‘Assessment of the Situation of Local Governments’ (2013) <http://eregion.wzp.pl/sites/default/files/ocena-sytuacji-samorzadow-lokalnych.pdf > accessed 1 December 2019.

[10] Position of the 32nd General Assembly of the Association of Rural Communes of the Republic of Poland of 19 June 2018 on amendments to the law on the division and change of gminas’ borders, <http://www.zgwrp.pl/attachments/article/1352/XXXIIZO_stanowisko_granice.pdf> accessed 1 December 2019.

Katarzyna Kubicka-Żac, ‘Gminy wiejskie chcą lepszej ochrony swych granic [Rural Gminas Demand Better Protection of their Borders]’ (Prawo.pl, 27 April 2019) <https://www.prawo.pl/samorzad/gminy-wiejskie-chca-lepszej-ochrony-swych-granic,402541.html> accessed 1 December 2019.

[11] Aneta Kaczmarek, ‘Zmiany granic gmin. „Zbyt łatwo silniejszy zabiera ziemię słabszemu” [Changes in the gminas’ Borders. “Too Easily the Stronger Takes the Land from the Weaker”]’ (Portal Samorządowy, 7 November 2019) <https://www.portalsamorzadowy.pl/prawo-i-finanse/zmiany-granic-gmin-zbyt-latwo-silniejszy-zabiera-ziemie-slabszemu,134527.html.> accessed 30 November 2019.

[12] Ministry of Regional Development, ‘Concept of the Country’s Spatial Development 2030’ (2011) 167 <http://www.wzs.wzp.pl/sites/default/files/files/19683/89272000_1412985316_Koncepcja_Przestrzennego_Zagospodarowania_Kraju_2030.pdf > accessed 30 November 2019.

[13] Website of the Gdańsk-Gdynia-Sopot Metropolitan Area, <http://en.metropoliagdansk.pl/>.

[14] Website of the Metropolis of Poznań <http://metropoliapoznan.pl/strona,27,dzialalnosc.html>.

[15] Website of the Cracow Metropolis <http://metropoliakrakowska.pl/>.

[16] Website of the Warsaw Functional Area <https://omw.um.warszawa.pl/>.

[17] Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy, ‘Programy Europejskiej Współpracy Terytorialnej i Europejskiego Instrumentu Sąsiedztwa’ (undated) <http://www.ewt.gov.pl/strony/o-programach/przeczytaj-o-programach/> accessed 1 December 2019.

Intergovernmental Relations of Local Governments in Poland: An Introduction

Andżelika Mirska, University of Warsaw

The model of a unitary state, adopted by Poland, assumes that the legislature is undivided – it is wielded only by the Polish Parliament (two chambers: Sejm and Senate). The principle of administrative decentralization means a division of the executive. It is wielded by the authorities of the Polish state (the President of the Republic of Poland and the government -The Council of Ministers of the Republic of Poland with the central government that is centralized and subject to the governance of the government). The local government has functioned within the executive since 1990. It has fulfilled a part of the tasks of the executive, but it is not subject hierarchically to the government. The local government (in Poland: territorial self-government) is independent in its activities undertaken for the good of its members (residents). However, its activities cannot violate the law (the Constitution of the Republic of Poland, acts, regulation, the EU law). Legal supervision is a mechanism which is triggered when the law is violated by local government (there is no difference with regard to urban and rural municipalities). Supervision is exercised only by the authorities of the Polish state. The local government may challenge that supervision through a complaint lodged to an administrative court. Ultimately, therefore, the court settles the dispute between the state and local government (Article 166 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 1997: ‘The administrative courts shall settle jurisdictional disputes between units of local government and units of government administration’).

However, there are no governance dependencies or supervision relations between three levels of territorial self-government (gminas, powiats, voivodeship). Therefore, the relations between local governments are always voluntary and mutually agreed (only exceptions include situation relating to public security as well as unusual and emergency situations – which are precisely determined in the act).

The state-local government relations are manifold. On the one hand, the local government is subject to the state’s regulations and supervision. The scope of tasks and financial resources are regulated by the act – the local government must submit to them. On the other hand, the Preamble of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland includes the principle of cooperation between the public authorities, therefore, between the government and local government as well – for the common good. The principle of cooperation between the authorities, referred to in the Preamble, corresponds with the multi-level governance structure, well established in the modern science of public governance.

In the democratic state there are various mechanisms in place to enable the participation in the law-making process. With regard to the local government, the Joint Commission of the Government and Territorial Self-Government (Komisja Wspólna Rządu i Samorządu Terytorialnego) has functioned in Poland since 1993. It is ‘the forum for the elaboration of a joint position of the central government and local government’. The local governments are formed by the representatives of all-Poland organizations of local government units, both representing the interests of urban and rural municipalities, including metropolises.

The Polish law guarantees the gminas, powiats and voivodeship the right to establish associations. Their objective should be to support the idea of local government and to defend their common interests. These associations can be established by the units of one local government level, but they can also include the units of different levels. The Association of Polish Local Governments (gminas, powiats, voivodeships) is such an association established in 2017. The association refers to the Christian values what is novel among the all-Poland associations which do not declare a worldview orientation in their statutes.

The primary role is played by 6 all-Poland local government organizations: the Union of Polish Metropolises (Unia Metropolii Polskich); the Union of Small Polish Towns (Unia Miasteczek Polskich); the Association of Polish Cities (Związek Miast Polskich); the Association of Rural Communes of the Republic of Poland (Związek Gmin Wiejskich Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej); the Association of Polish Powiats (Związek Powiatów Polskich); the Association of Voivodeships of the Republic of Poland (Związek Województw Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej).

There is a range of examples of associations of a regional or even local nature (e.g. the Association of Communes and Powiats of Małopolska (Stowarzyszenie Gmin i Powiatów Małopolski), the Association of Communes and Powiats of Central Pomerania (Stowarzyszenie Gmin i Powiatów Pomorza Środkowego). There are also associations which determined their scope of interest, e.g.: the Masovian Association of Communes for the Development of Information Society (Mazowieckie Stowarzyszenie Gmin na Rzecz Rozwoju Społeczeństwa Informacyjnego), the Association of Health Resort Communes of the Republic of Poland (Stowarzyszenie Gmin Uzdrowiskowych RP).

All associations are subject to the registration in the court (the entry to the National Court Register) and legal supervision by the state.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Website of the Association of Polish Cities, <http://www.miasta.pl/en>

Website of the Association of Voivodeships the Republic of Poland, <https://zwrp.pl/en/>

Website of the Joint Commission of Government and Territorial Self Government, <http://kwrist.mswia.gov.pl>

Website of the Union of Polish Metropolises, <https://www.metropolie.pl/en/>

People’s Participation in Local Decision-Making in Poland: An Introduction

Andżelika Mirska and Marcin Sokołowski, University of Warsaw

The process of local community empowerment which started in Poland after 1989 was an important element of political transformation. The priority was to return to guarantee the residents the right to participate in exercising the public authority and in deciding on own matters. The adopted model of local government is based on representative democracy. The Polish citizens and EU citizens residing in Poland from the age of 18 years are guaranteed the active voting right. Similarly, it applies to the passive voting right. The election for the mayor in the community is the exception: the passive voting right is only granted to Polish citizens from the age of 25 years old.

Since the beginning of local government an instrument of direct democracy – a local referendum was also introduced. The decisions are binding when certain requirements are met. The local referendum can be conducted at any level of local government, i.e. in the gmina, powiat and voivodeship. All own tasks of local government, except the matters explicitly excluded by law (a negative catalogue), are the subject of the referendum. A special referendum is the referendum on self-taxation of residents of the gmina for public purposes (this is an exception to the general rule that the taxes can be imposed on the citizens only by the Polish Parliament). Furthermore, the residents have the right to recall in the referendum these local government bodies which were elected by them by direct universal suffrage. According to the constitutional principle in Poland all representative bodies are elected by direct universal suffrage. Since 2002 the executive body in the gmina is also elected by direct universal suffrage. The executive bodies in the powiat and voivodeship are elected and recalled by the representative bodies.

A local referendum is held at the initiative of the representative body or at the request of inhabitants. The initiative to hold a referendum at the request of the local government unit residents may be applied by:

- the minimum 5 citizens (referendum in the gmina), minimum 15 citizens (referendum in the powiat and voivodeship);

- a political party local branch operating in a given local government unit (gmina, powiat, voivodeship);

- a social organization with legal personality and operating in a given local government unit (gmina, powiat, voivodeship).

The period of collecting signatures lasts 60 days. In order to hold a local referendum to be valid, it must be signed by:

- 10 per cent of the gmina or powiat residents eligible to vote;

- 5 per cent of voivodship residents eligible to vote.

The criterion for the validity of a referendum in Poland is a voter turnout. It was set at 30 per cent. The result of a referendum is conclusive if more than half of the valid votes were cast in favor of one of the solutions in a matter put to a referendum (on self-taxation of inhabitants for public purposes – the majority of 2/3 of valid votes).

The 30 per cent turnout threshold has been modified since 2005 in the case of a referendum on the dismissal of a directly[1] elected local authority. Currently, the minimum turnout is 3/5 of the participants in the election of the body[2] to be dismissed.

In general, approx. 10 per cent of referendums are successful, the main problem is reaching the required turnout. Average turnout is 17 per cent. Most frequently referendums are held in gminas, very rarely in powiats, and incidentally in voivodeships. In gminas, referendums on the dismissal of the mayor are held most often. The referenda on the recalling of the executive bodies in the large cities elicit the particular interest of the public (negative result: Warsaw 2013, Bytom 2017; positive result: Olsztyn 2008, Elbląg 2013).

| Three terms of office 2002-2014 | Term of office 2014-2018 | |||

|

Body |

Number of referendums | Valid referendums | Number of referendums | Valid referendums |

| The gmina council | 67 | 10 | 14 | 1 |

| The mayor | 246 | 32 | 44 | 4 |

| The powiat council | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The voivodeship assembly (council) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 1: Local referendums on the dismissal of bodies.[3]

The table shows that since 2002 (when the direct election of the mayor was introduced) a total of 380 referendums have been held only 9 per cent of which were valid. Referendums on the dismissal of the mayor are most common and they account for 76 per cent of all referendums on the dismissal of local government bodies.

If we consider the structure of gminas in which referendums on the dismissal of the gmina’s council and/or the mayor were held in the years 2014-2018, the majority of them were either rural gminas (26) or urban and rural gminas (12), small towns (6), large cities with powiat rights (2).

Substantive referendums are carried out much less frequently. The report of the Chancellery of the President of the Republic of Poland of 6 September 2013 on local referendums indicates that in the period 2010-2013 there were 111 referendums on the dismissal of local authorities and only 22 substantive referendums.[4]

In 2011, a provision was introduced to the Act on Gmina Self-Government on the possibility of holding a local referendum at the request of inhabitants on the change in the establishment, merger, division and liquidation of a gmina and the establishment of the gmina’s borders.

The institution of ‘citizens’ resolution-making initiative’ (obywatelska inicjatywa uchwałodawcza) was provided for in the rules on law making by the local government at all three levels of local government. The draft resolution presented by the residents becomes the subject of the agenda of the legislative body of local government unit at the next session after the presentation of the draft resolution, however, not later than after expiry of 3 months from the date of the presentation of the draft resolution.

Besides the direct exercise of local government authority (local government elections and local referenda) there is a series of opportunities for the residents to participate in the decision-making processes. The instruments of participation were institutionalized in Poland gradually. Since the beginning the acts on local government guaranteed the residents the right to be consulted – the consultation can be carried out in all matters important for the residents. The public consultation allows the members of local government community to participate in the conduct of public matters. The acts make it obligatory to conduct the consultation, inter alia, with regard to: (i) change to the boundaries, merger, division, liquidation of local government units, (ii) establishment of auxiliary units in municipalities (districts, civil parishes).

The consultation may also take the form of permanent consultation bodies. The Act of 8 March 1990 on Gmina Self-Government provides for two such bodies: youth council (since 2011) and council of seniors (since 2013).

Poland also belongs to the states which promote new forms of participation, such as a participatory budget. The first participatory budget came into operation in Sopot in 2011, then, fairly quickly, such initiatives were undertaken by larger or very large cities. Till 2018 the local government authorities based on the general provisions of local government acts on the consultation. In 2018 the acts on Gmina Self-Government, on Powiat Self-Government and on Voivodeship Self-Government were extended by the regulations on the ‘citizens’ budget’ (budżet obywatelski) as a special form of the consultation. It is surprising that the act made it obligatory to establish a participatory budget in the cities with powiat rights. Therefore, it is a characteristic element of the system of large cities.

In Poland there is also an instrument of budgetary participation dedicated only to the rural communes – ‘The Village fund’ (fundusz sołecki). Since its inception in 2009 it is anchored in the act, now, it is the Act of 2011 on the Village Fund.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Makowski K, ‘Participatory Budgeting in Poland AD 2019: Expectations, Changes and Reality’, (2019) 48 Polish Political Science Yearbook 642 <https://czasopisma.marszalek.com.pl/images/pliki/ppsy/48-4/ppsy2019409.pdf>

Sidor M, ‘The Process of Enhancing Citizens’ Participation in Local Government in Poland’ (2012) 3 Socialiniai Tyrimai. Social Research 87 <http://www.su.lt/bylos/mokslo_leidiniai/soc_tyrimai/2012_28/sidor.pdf>

[1] In gminas, inhabitants directly elect both bodies (the gmina council and the mayor), in the powiats and in the voivodeships, only the representative body (the powiat council and the voivodeship assembly).

[2] Act of 15 September 2000 on Local Referendum.

[3] Own work based on ‘Referenda odwoławcze w kadencji 2014 – 2018’ (Referendum lokalne) <http://referendumlokalne.pl/referenda-w-kadencji-2014-2018> accessed 1 December 2019 and Paweł Cieśliński, ‘Referendum lokalne w Polsce – ale jakie?’ (2016) 3 Civitas et Lex 28, 33.

[4] ‘Referenda Lokalne’ (Chancellery of the President of the Republic of Poland 2013) <https://www.prezydent.pl/gfx/prezydent/userfiles2/files/2013_pliki_rozne/raport_referenda/referenda_lokalne_raport_kprp_20130925_131447.pdf> accessed 10 December 2019.