Partner Institutions: University of Fribourg, Institute of Federalism, and Ximpulse GmbH

The System of Local Government in Switzerland

Flavien Felder, IFF Institute of Federalism, University of Fribourg

Types of Local Governments

The Swiss model of federalism, based on the principle of subsidiarity, is structured in three layers of political representation, i.e. the Confederation (national government), the cantons and the municipalities. The Constitution of the Swiss Confederation, however, focuses on two layers only, the national and cantonal. In its Article 1 it not only lists the official 26 cantons but also gives them constitutive effect. In Article 3 it sets the rules for the power-sharing arrangements between the Confederation and the cantons: ‘The Cantons are sovereign except to the extent that their sovereignty is limited by the Federal Constitution. They exercise all rights that are not vested in the Confederation.’ However, one must bear in mind that the term ‘competent’ would be more appropriate than ‘sovereign’ to describe the power vested in the cantons. In fact, the cantons have competence on all the tasks and duties that do not fall on the Confederation. But they nevertheless remain subdued to the Confederation, as the majority of the other cantons can impose their will on a canton via a revision of the Swiss Constitution. Indeed, according to the Article 48(a) of the Swiss Constitution, at the request of interested cantons, the Confederation may declare intercantonal agreements to be generally binding or require cantons to participate in intercantonal agreements in the following fields:

- the execution of criminal penalties and measures;

- school education in the matters specified in Article 62(4);

- cantonal institutions of higher education;

- cultural institutions of supra-regional importance; e. waste management;

- waste water treatment;

- urban transport;

- advanced medical science and specialist clinics;

- institutions for the rehabilitation and care of invalids.

The Federal Constitution does not attribute any competence to regulate local government to the national government. The municipalities are therefore created by and subjected to cantonal regulation. Thus, each canton defines the status and the competences of its municipalities in its cantonal constitution and legislation. We therefore differentiate 26 systems of municipalities corresponding to each of the 26 Swiss cantons. Still, one can identify five main types of municipalities:

- the classical political municipalities which are called commune in French, comune in Italian and Gemeinde, Ortsgemeinde or Einwohnergemeinde in German depending on the cantons. They are the basic general-purpose type of municipality;

- the so-called bourgeoise municipalities that have survived from the Middle Age in some cantons. When in 1798 the Helvetic Republic is proclaimed; the cantons are put on an equal footing and the inhabitants of the Swiss territory receive the Swiss citizenship. The original bourgeois do not agree to share the communal properties (lands, forests, etc.) with the new bourgeoise. Thus, the bourgeoise municipalities keep the control over the communal properties and the political municipalities guarantee the political rights to the new bourgeoise. As of today, in the cantons where such bourgeoise municipalities remain, they are mainly land owners and service providers (for example retirement houses, subsidized apartments, young offenders’ facilities, etc.);

- the ecclesiastical community is the territorial division that is attached to a church and that is often called parish (paroisse in French). They are a single-purpose body;

- the so-called scholar commune commune scolaire is also a single-purpose body that deals with the school system on a certain territory within the limits assigned by the canton and that does not automatically match with the political municipality. For example, the school program remains a cantonal competence but the decision to build the school or to organize the carriage of school pupils is, to a large extent, delegated to the scholar municipalities;[1]

- other types of municipalities that exist in some cantons.

Finally, one must add that the majority of the Swiss cantons have put in place an intermediary political level between the cantons and the municipalities called the district (district in French, Bezirk, Verwaltungsregion, Verwaltungskreis, Wahlkreis, Amtei or Amt in German, distretto in Italian). Out of the 26 cantons, only six do not have such a subdivision. These districts are very different from each other but they usually correspond to a group of municipalities. Again, the cantons hold the primary competence regarding their internal organization and scope.

Legal Status of Local Governments

The constitution framework that prevailed until 1999 did not mention municipalities, unless incidentally. Only the adoption of a new constitution that year ensured that local autonomy was granted constitutional protection.[2] Article 50 reads as follows: (i) ’The autonomy of the communes is guaranteed in accordance with cantonal law.’; (ii) ‘The Confederation shall take account in its activities of the possible consequences for the communes.’; (iii) ‘In doing so, it shall take account of the special position of the cities and urban areas as well as the mountain regions.’

The effect of the new provision is limited. The extent of local autonomy remains in the hands of the cantons (‘in accordance with cantonal law’) and each of them thus continues to autonomously define its internal governance system. Only as far as cantonal law provides for municipal autonomy, it is guaranteed by the Federal Constitution. Consequently, municipal autonomy is justiciable and the Federal Supreme Court hears disputes concerning violations of it (Article 189(1)(e)). When it does so, it refers to the cantonal constitution and the cantonal legislative framework to determine the scope of local autonomy and decide whether the canton has impinged on it or not.

If the Article 50(2) of the Constitution constrains the Confederation, while fulfilling its tasks (e.g. military, national highways), to be considerate of municipalities, it does not confer additional jurisdiction on the Confederation. Essentially, this constitutional provision aims at fostering vertical cooperation between the three institutional levels of the Swiss federal structure but without bypassing the intermediary level, the cantons. The article refers specifically to the urban-rural divide and explicitly compels the national government to take account of the special priorities and needs of cities and urban areas on the one hand and mountain regions on the other hand. Among the concrete initiatives, the Tripartite Conference can be mentioned. It will be discussed at length further in the Country Report.

(A)Symmetry of the Local Government System

As mentioned above, there are 26 systems of local government corresponding to the 26 Swiss cantons. Thus, there are considerable differences regarding the rules that apply to urban local governments (ULGs) and rural local governments (RLGs), etc. For example, the Canton of Zürich has granted a special status to the cities of Zürich and Winterthur. Most cantons, however, are based on a symmetric system and allocate the same tasks and responsibilities to all municipalities, irrespective of their size.

Despite of the wide variety of cantonal local government arrangements, some common features can be identified. Schmitt demonstrates that all municipalities are run by an executive council of five to ten members who are elected by the citizens and who are compelled to take decisions on a collegial basis.[3] While they traditionally are not paid for their work, the elected members of municipalities’ councils in the ULGs tend to be professionals.

As regards legislative power, small municipalities (not to say RLGs) have citizens’ assemblies that meet regularly to pass new laws and/or to elect the executive council members and other authorities. On the contrary, some cantons have compelled larger municipalities (ULGs) to create a parliament, i.e. an elected legislative body representing the citizens. As Schmitt notes, the Canton of Fribourg has adopted the Law on the Municipalities (Loi sur les communes in French) that requires eight specific municipalities to set up such a parliament while municipalities with over 600 inhabitants are only invited to do so.[4] Smaller municipalities can keep their citizens’ assemblies.

Finally, Schmitt puts a light on an interesting paradox: while municipalities still enjoy a large set of competencies and have the right to collect taxes (and set the tax rates), judicial power is not granted to the municipalities. In fact, the lowest judicial level is, in some cantons, the district’s judge. Once again, one must look carefully at all the 26 cantonal organizations in order to grasp the subtleties of the local government systems that make Swiss federalism so complex.[5]

Political and Social Context in Switzerland

If the prominent role and the many responsibilities conferred to the municipalities have long been praised and recognized as a key factor for the success of the Swiss political model, one must note that they tend to lose their luster. In fact, the degree of autonomy enjoyed by the municipalities decreases due to the increasing requirements (land use planning, environmental protection, social aid, waste management, etc.) from the Confederation, the cantons and, to some extent, the people themselves. The democratic pressure (complexity of the legal frameworks, over technical policy fields, procedural overload, etc.) on the municipalities is difficult to manage, especially for non-professional elected representatives and somehow encourages the centralization of the decision-making power and the pooling of local tasks and duties at a superior level.

In the last 30 years, Switzerland has thus witnessed a strong acceleration of the number of amalgamations of its municipalities. From more than 3,200 municipalities in 1999, the number has dropped to approximately 2,200 municipalities in 2018. While the rural municipalities tend to merge, it can be observed that urban municipalities tend instead to agglomerate[6] via different types of inter-municipal agreements. In any case, cantons and municipalities follow their own path with little interference from the national government. Today, approximately two thirds of the Swiss population is concentrated in the cities’ centers [7]or agglomerations.

According to 2017 data, the 2,212 Swiss municipalities are relatively small, with 1,060 inhabitants on average, but very different in size. The smallest is Corippo with 12 permanent inhabitants and, like many others, spreads on less than 1 km². The largest in terms of territory is Scuol with 438.62 km² and the most populated is Zurich with 400,000 inhabitants. Many municipalities being unable to cope with the organizational requirements of today’s life (school facilities, firefighter’s service, water sanitation, etc.) and finding it difficult to recruit personnel, a strong process of merging local authorities has begun some sixty years ago and has accelerated in the last thirty years.

The four main coalition parties, namely the FDP. The Liberals, the Christian Democratic People’s Party, the Social Democratic Party and the Swiss People’s Party are all represented at the Federal level and in almost all the 26 cantons. Interestingly, in the urban cities, the traditional political parties are well organized and represented while in the smaller rural municipalities, political parties are less active. The peculiarity of small municipalities where every citizen knows each other means that people vote first for a specific candidate rather than for the parties.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation of 18 April 1999, SR 101

Federal Act on Political Rights of 17 December 1976, SR 161.1

Fribourg Cantonal Law on the Municipalities of 25 September 1980, SR 140.1

Loi cantonale fribourgeoise relative à l’encouragement aux fusions de communes [Fribourg Cantonal Law on the Encouragement of Fusions of Municipalities] of 9 December 2010, RSF 141.11

Ordonnance indiquant les noms des communes et leur rattachement aux districts administratifs [Ordinance on the Names of Municipalities and their Attachment to Administrative Districts] of 24 November 2015, RSF 112.51

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Aubert JF, Traité de droit constitutionnel Suisse, Neuchâtel (Ides et Calendes 1967)

Roulet Y, Interview with Bernhard Waldmann, ‘Les villes mettent le fédéralisme suisse au défi’ Le Temps (17 October 2017)

Schmitt N, Local Government in Switzerland: Organisation and Competences (forthcoming)

[1] Nicolas Schmitt, Local Government in Switzerland: Organisation and Competences (forthcoming).

[2] Schmitt, Local Government in Switzerland, above.

[3] Schmitt, Local Government in Switzerland, above.

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid.

[6] According to the Federal Office of Statistics, the agglomeration can be defined as follows: An agglomeration is a group of municipalities with a total of more than 20,000 inhabitants (incl. overnight stays in converted hotels). It consists of a dense center and usually a crown. The delimitation of the crown is based on the intensity of the commuter flows.

[7] According to the Federal Office of Statistics, the city-center can be defined as follows: The municipality which, among the central municipalities of an agglomeration, has the highest number of HENs (= sum of inhabitants, work places and overnight stays in converted hotels) is considered as a city-center. In some cases, it is possible for an agglomeration to have several central cities.

Local Responsibilities and Public Services in Switzerland: An Introduction

Flavien Felder, IFF Institute of Federalism, University of Fribourg

The Swiss Federal Constitution provides in its Article 50 that the autonomy of the communes is guaranteed in accordance with cantonal law and that the Confederation shall take account in its activities of the possible consequences for the municipalities. In doing so, it shall take account of the special position of the cities and urban areas as well at mountain regions. This provision does not provide the Confederation with additional competence over the municipalities but rather invites the three institutional levels to intensify the vertical dialogues and to cooperate more efficiently.

In Switzerland, cantonal constitutions and statutory laws govern the legal frameworks in which municipalities operate. Therefore, the federal system is very heterogeneous, and it is difficult to have a clear picture of the municipalities’ competencies in all 26 Swiss cantons. One would have to study carefully the legislation of each specific canton to define the degree of autonomy held by each municipality.

The academic literature confirms one general conclusion: the French-speaking cantons tend to be more centralized than the German-speaking cantons.[1] Scholars also point out that, for historical and geographical reasons, municipalities in the Canton of Grisons/Graubünden exercise a high degree of autonomy, while those in the cantons of Basel-City and Geneva enjoy relatively limited self-determination. In fact, the latter two cantons are sometimes called ‘canton-city’[2] because of the small number of municipalities and the strong interdependence between the city and the canton. While the Canton of Basel was split in two half-cantons in 1833 (Basel-City and Basel-Country; the former being composed of only 3 municipalities), the Canton of Geneva has 40 municipalities and discussions to merge the municipalities with the Canton of Geneva come up regularly.

Therefore, in general terms municipalities enjoy what can be called a residual autonomy although the precise terminology differs from one canton to the other. They are competent when the local tasks are neither incumbent on the confederation nor on the canton.[3] Among them, taxation, policing, land planning, public roads, environment protection, public education, social aid, naturalization and culture typically lies in the hands of the municipalities although it is not an exclusive competence but usually shared with the cantons and often only executed by the municipalities. Of all of them, culture is probably the policy field in which municipalities have the most leeway.[4]

As the Swiss federal system typically is the result of independent states coming together to form a confederation, there is certainly no uniform scheme of responsibilities throughout the country. Competencies in the policy fields listed above are neither distributed according to clear criteria nor according to the capabilities of the municipalities, whether rural or urban.

Interestingly, the relative broad municipal autonomy allows them to outsource some services to the private sector, including policing which of course calls into question the monopoly of the state for sovereign issues and challenges the democratic control over security forces.[5]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Guerry M, ‘La privatisation de la sécurité et ses limites juridiques’ (2006) 2 La Semaine judiciaire 141

Grodecki S, ‘Les compétences communales – comparaison intercantonale’ in Thierry Tanquerel and François Bellanger (eds), L’avenir juridique des communes (Schulthess 2007)

[1] Stéphane Grodecki, ‘Les compétences communales – comparaison intercantonale’ in Thierry Tanquerel and François Bellanger (eds), L’avenir juridique des communes (Schulthess 2007) 74.

[2] ibid 74.

[3] ibid 28, 29.

[4] Grodecki, ‘Les compétences communales’, above, 74.

[5] Michael Guerry, ‘La privatisation de la sécurité et ses limites juridiques’ (2006) 2 La Semaine judiciaire 141.

Local Financial Arrangements in Switzerland: An Introduction

Flavien Felder, IFF Institute of Federalism, University of Fribourg

In Switzerland, all three tiers of government, namely the Confederation, the cantons (states) and the communes (municipalities), have the right to levy taxes to the extent that the Federal Constitution does not limit these public bodies (Article 3 of the Constitution). While the two upper tiers enjoy a full sovereignty, the communes only have a derived sovereignty as their right to levy taxes can be limited by the cantons.

The fiscal autonomy of the communes is rooted in the Swiss federal system. Although one sees a trend towards more centralization of competencies, the principle of subsidiarity is still a pillar of the system: tasks that can be done at a lower political level should be done at a lower level, closer to the people concerned by them. Thus, Swiss communes are not in charge of minor duties only (waste removal) but are also competent for tasks of higher importance such as education, social care, etc. Consequently, the communes levy approximately 20 per cent of the total tax revenue of the three administrative tiers[1].

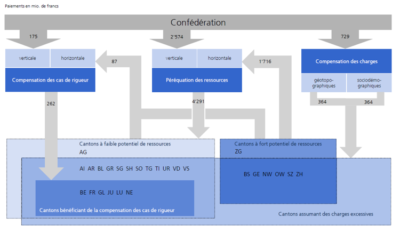

In the case of Switzerland, where budgets are highly decentralized, the equalization of resources and the equalization of charges are two tools that help mitigate imbalances among public bodies. These imbalances can be of different natures. For example, the amount of tax revenue can be very unbalanced (i.e. equalization of resources) and the burden of financing public services can be highly unevenly distributed between urban and rural communes (i.e. equalization of charges).

In 2008, Switzerland introduced a fiscal equalization system between the Confederation and the cantons accompanied by an inter-cantonal distribution (subnational level). The Federal Act on fiscal equalization and expenditures compensation entered into force in 2003 and was revised in 2019. Practically, the financial flows are multiple, horizontal and vertical, and the overall system is quite complex. A chart resuming the system is available on the website of the Swiss Federal Department of Finance:[2]

Figure 1: Fiscal equalization system between the Swiss Confederation and the cantons.

Figure 1: Fiscal equalization system between the Swiss Confederation and the cantons.

At the local level, similar mechanisms are in place within the cantons. As each canton developed its own specific intercommunal equalization system, carrying out a comprehensive survey of the different schemes is a challenging endeavor. In 2013, the think tank Avenir Suisse published an interesting comparative monitoring of all the 26 intercommunal systems.[3] The author underlined that the majority of the intercommunal equalization systems were often unnecessarily complicated, encouraged spending behaviors and thus maintained inefficient municipal structures.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

—— ‘Debt Brake’ (Federal Finance Administration, 1 September 2020) <https://www.efv.admin.ch/efv/en/home/themen/finanzpolitik_grundlagen/schuldenbremse.html>

—— ‘National Fiscal Equalization’ (Federal Department of Finance, November 2019) <https://www.efd.admin.ch/efd/en/home/themen/finanzpolitik/national-fiscal-equalization/fb-nationaler-finanzausgleich.html>

—— ‘The Swiss Tax System’ (Federal Department of Finance, January 2020) <https://www.efd.admin.ch/efd/en/home/themen/steuern/steuern-national/the-swiss-tax-system/fb-schweizer-steuersystem.html>

Website of the Swiss Conference of the Cantonal Governments, <https://kdk.ch/fr/>

[1] In 2014, tax revenues (3 tiers) totaled CHF 131 billion: Confederation: CHF 60,6 billion; cantons: CHF 43,5 billion; communes: CHF 26,8.

[2] ‘2021 fiscal equalization payments in CHF mn’ (Federal Department of Finance) <https://www.efd.admin.ch/efd/en/home/themen/finanzpolitik/national-fiscal-equalization/fb-nationaler-finanzausgleich/grafik-nfa.html> last accessed 15 February 2020.

[3] Lukas Rühli, Monitoring des Cantons 5: Le Labyrinthe de la péréquation financière (Avenir Suisse 2013) 21.

The Structure of Local Government in Switzerland: An Introduction

Eva Maria Belser and Flavien Felder, IFF Institute of Federalism, University of Fribourg

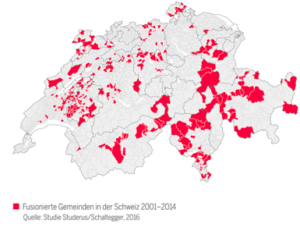

The number of local governments in Switzerland has decreased massively during the last two decades. When the federation in 1848 came into being, it was composed of 25 cantons and 3,203 communes. Three hundred of them disappeared through amalgamation until 2000 (one hundred of them because of a profound structural reform in the Canton of Thurgau). Then, the local government landscape began to change massively. In 2012, the number of municipalities decreased to 2,495, and in 2018, the number went down to 2,222. Currently, a few hundred municipalities are in the process of amalgamation or consider doing so. This process amounts to a total reduction of about one third of communes/municipalities and characterizes an overarching tendency in Switzerland’s structure of local government.

The process of mergers is driven either by the communes themselves (bottom-up) or by the cantons (top-down). The Confederation has no competence to interfere with local government structures, or to plan, implement or prevent mergers from taking place.

While some cantons have massively reduced the number of communes, others have not. The great variance between cantons are not due to demographic differences but to different legal regimes and also political cultures. One group of cantons allows for mandatory mergers of communes (but rarely uses the mechanism), a second group financially incentivizes mergers, and a third group leaves the initiative entirely to the communes. The graph to the right illustrates that the process has been unequally distributed across the whole country. Mergers most frequently take place in cantons offering support and financial benefits to interested communes. Major territorial restructuring has taken place in highly fragmented and partly rural cantons, such as Glarus, Ticino, Fribourg/Freiburg, Graubünden/Grischun/Grigioni, and Vaud, smaller ones in most cantons.

Mergers equally occur in rural and urban settings but follow completely different motives. In rural environments, they typically respond to financial constraints, difficulties to find adequate personnel and to deliver increasingly complex local services. In urban areas, mergers serve to bring cities, which have grown into spreading agglomerations with surrounding communes, into one political entity and to improve planning and urban development on a scale corresponding to the social and structural reality. However, numerous planned mergers have failed, mostly due to popular refusal driven by strong local identities or financial considerations.

Because of rapid urbanization and the very different and flexible approaches of cantons to this phenomenon, differences of communes within cantons and between cantons are increasing in many ways. The largest commune of Switzerland, the City of Zurich, has more than 400,000 inhabitants, the smallest one, Corippo in the Canton of Ticino (currently merging with neighboring communes), only 14. In the mountainous Canton of Graubünden/Grischun/Grigioni, more than half of the now 128 communes are populated by less than 1,000 people; in the urban Canton of Basel-City, there are only three communes, one of them a very small municipality. The great differences amongst the communes, with respect to population, area, as well as human and financial resources, are a challenge to the symmetric structure of federal Switzerland.

Inter-municipal cooperation plays a crucial role. It is usually based on inter-municipal treaties, which are bilateral or multilateral, and often lead to the establishment of inter-municipal institutions and associations. While the democratic deficit of these structures is often deplored, communes confirm that inter-municipal cooperation is becoming increasingly important. It is practiced in order to profit from scale effects and to prevent further centralization of competences at the cantonal level. Most Swiss communes cooperate in the field of population protection, fire services, health services, education, water and sewage as well as waste disposal; more than half of all communes seek partnerships in the field of social aid and assistance to the elderly as well.

To the surprise of most observers, recent research has questioned the efficiency of communal mergers in certain respects. Researchers have been able to show that the process of merging municipalities itself is costly and, in most cases, does not immediately produce the expected cost-saving effects. This is presumably because many merging communes have already strongly cooperated before their union and realized the cost-saving potential before merging. The research results question whether cantons should continue to strongly incentivize amalgamations or not.[1]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

—— ‘Typology of Municipalities and Urban-Rural Typology’ (Federal Statistical Office) <https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/espace-environnement/nomenclatures/gemtyp.html>

Martin Schuler, Dominik Ullmann and Werner Haug, ‘Evolution of the Population of Municipalities 1850-2000’ (Federal Statistical Office 2002) <https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/catalogues-banques-donnees/publications.assetdetail.340621.html>

Website of the platform for regional development in Switzerland <https://regiosuisse.ch/fr/news/nouvelle-typologie-communes-nouvelle-typologie-urbain-rural-lofs >

[1] See Christoph Schaltegger and Janine Studerus, ‚Gemeindefusionen ohne Spareffekt‘ NZZ (14 March 2017).

Intergovernmental Relations of Local Governments in Switzerland: An Introduction

Erika Schläppi and Kelly Bishop, Ximpulse GmbH

It is not possible to make generalized statements on the relations between canton and municipalities for all of Switzerland. In the Swiss federal system, the cantons (and not the Confederation) determine the status and role of municipalities. Each canton has its own way to organize relations with municipalities, allocate competences and organize municipal finances. Thus, intergovernmental relations differ largely among the cantons. Because of historic and cultural reasons, the cantons of the French speaking part have a more centralistic approach, while municipalities in the eastern and central part of Switzerland show a more decentralized structure when it comes to the allocation of tasks. Our examples mainly refer to the Canton of Berne and its relation to the Bernese municipalities. The canton is perceived as a bridge builder between the German and the French speaking cantons and their traditions. Regarding municipal autonomy it might be considered as a kind of Swiss average. The Canton of Berne is one of the biggest cantons in terms of territory as well as the number of residents (around 1 Mio, 16.3 per cent foreign passport holders according to the census of 2018). The City of Berne is the capital of the canton as well as of the Swiss Confederation. Socially and politically, the canton is quite heterogeneous: relatively big urban and peri-urban areas are coupled with reasonably big rural and mountainous areas that are thinly populated. Around 10 per cent of the residents are mainly speaking French, the big majority are German speakers. All these elements make the Canton of Berne an interesting object of observation.

In Switzerland there is hardly any public task that is exclusively performed by municipalities, without any central steering or co-financing, and the distribution of responsibilities is constantly evolving. In all important policy areas there is a sharing of competence that requires a cooperative set-up between cantons and municipalities at various levels. As a rule, the canton focuses on the adoption of the legal framework, establishes a control system and exercises oversight. With the increasing mobility and the evolving complexity of public tasks it is not surprising that generally, the central competences are increasing and the scope of action of municipalities tend to be decreasing. The principle of subsidiarity (Article 5(a) of the Federal Constitution) is providing (federal) orientation for the allocation of competences, stating that tasks should be performed as close to the population as possible. Thus, the primary schools, social welfare, local spatial planning, public security, local transport, water supply and waste management are most often in the competence of municipalities – but there are still many federal and cantonal rules and standards that are to be considered by municipalities.

Financial equalization is an important pillar of the Swiss political system, allowing for financial collaboration and cooperation among cantons and municipalities. At the level of the Confederation it focuses on the equalization of resources as well as the equalization of financial burdens between cantons. The same idea of equalization is also applied at cantonal level, between municipalities. Regarding the allocated tasks, the cantonal regulations hardly make any difference between municipalities that, in terms of inhabitants, tend to be bigger in urban areas and smaller in rural areas. The cantonal specifications and standards are the same, the cantonal controlling and oversight does not differentiate between urban or rural, big or small municipalities. However, the Canton of Berne is contributing to the financing of municipal tasks in many respects. The cantonal share is calculated according to the constitutional principle of ‘financial equivalence’: The canton pays what it is commissioning. For example, the canton has adopted a relatively dense regulation concerning the salaries of primary teachers, the curricula and the required lessons for primary schools – thus, the canton pays 70 per cent of the salary expenses for primary school teachers. The rest of the salary expenses are financed by the municipalities, through their own tax income.

Today, municipalities with low financial capacities would not be able to finance their tasks by their own tax income. Thus, a horizontal equalization scheme has been developed. This scheme is mainly alimented by payments of well-off municipalities but the canton is also contributing funds. The payment scheme for equalization of resources is meant to allow for an adequate (but not full) equalization of standards among municipalities, independent of their financial capacities. In addition, the equalization of burdens aspires to balance specific burdens on the municipalities that are caused by social demography, geographical challenges (for example, the cost of an extensive water supply or road system in a thinly populated rural area), or specific tasks of urban centres (Zentrumslasten). The equalization payments are calculated based on a cantonal law and decided upon by the cantonal government, taking into account a very differentiated set of parameters that is adjusted regularly. The equalization system in the canton of Berne has grown over the years into a complex body of horizontal and vertical, direct and indirect, general and sectorial mechanisms. The impact of the equalization scheme on the canton and (urban and rural) municipalities is regularly evaluated and assessed in the light of the context dynamics, and adjustments are frequently thematized and discussed in the political debate..

Every Swiss municipality is participating in intermunicipal cooperation in multiple ways and forms and obtains services from third parties. From the political point of view as well as from the accountability perspective, there is hardly any difference whether the (public) task is performed by the municipality itself, in cooperation with other municipalities or by third parties. In the Canton of Berne, in average, around half of the municipal budgets are spent by own activities, around a third of the budgets go to legally autonomous bodies owned by the municipalities (such as associations of municipalities, or shareholder companies owned by municipalities), and one sixth of the budget is spent for buying services from third parties. Smaller and even medium size municipalities have difficulties to perform their tasks according to the required quality standards and the cooperation with other municipalities or the private sector allows them to improve their professional performance. However, in many cases, cooperation is not cheap – it will not lead to lower costs as it is often hoped for.

Intermunicipal cooperation is mainly organized in two legal forms: the association of municipalities and the assignment of one municipality to perform tasks of others. The association of municipalities is a legally autonomous municipal body that is foreseen by the cantonal municipal law. Individual municipalities commission this body to fulfill a certain task. The association is organized in a legislative and an executive body and acts according to a set of rules that must be adopted by the participating municipalities. Essential changes to the delegated tasks or the funding parameters cannot be adopted by the majority within the association against the will of participating municipalities. This form of cooperation has proved itself many times. However, the challenge is that the steering of the associations is often mediated through individual representatives in their decision-making bodies, there is often a certain self-reinforcing momentum, and municipal authorities have difficulties to have their voices as owners heard. The second legal form is the contracting of one municipality to fulfill tasks on behalf of other municipalities. The advantages of the association (for example, the participation of the delegating municipalities in decision-making processes) can also be reflected in the contract. The advantage of this form is that the fulfillment of the task is embedded in an existing municipal set-up and can profit from existing professional structures and administrative services. While these forms of intermunicipal cooperation are ruled by public law, municipal tasks are often also delegated to companies that are formally under private law, for example joint-stock companies or cooperatives that run a regional sports facility on behalf of various municipalities. Here again, the steering and the ensuring of accountability can be challenging. Increasingly, the participating municipalities do no longer engage in the steering boards of such companies but are agreeing among themselves on an owner strategy that they then commission to the private company for execution.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation, SR 101

Federal Law on Regional Politics (Bundesgesetz über Regionalpolitik), SR 901.0

Federal Regulation on Regional Politics (Verordnung über Regionalpolitik (VRP)), SR 901.021

Law on Municipalities of the Canton of Berne (Gemeindegesetz, BSG 170.11)

Law on Equalization of Finances and Burden of the Canton of Berne (Gesetz über den Finanz- und Lastenausgleich, BSG 631.1)

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Arn D, Friedrich U, Friedli P, Müller M, Müller S and Wichtermann J, Kommentar zum Gemeindegesetz des Kantons Bern (Stämpfli Verlag Bern 1999)

—— and Strecker M, ‘Horizontale und vertikale Zusammenarbeit in der Agglomeration’ (Tripartite Agglomerationskonferenz 2005)

Geser H and others, ‘Die Schweizer Gemeinden im Kräftefeld des gesellschaftlichen und politisch-administrativen Wandels’ (Institute of Sociology Zurich 1996)

Horber-Papazian K, ‘L’intervention des communes dans les politiques publiques’ (Doctoral thesis, EPFL Lausanne 2004)

—— and Jacot-Descombes C, ‘Les Communes‘ in Peter Knöpfel, Yannis Papadopoulos, Pascal Sciarini, Adrian Vatter and Silja Häusermann (eds), Handbuch der Schweizer Politik (5th edn, NZZ Libro 2014)

Ladner A and Mathys L, ‘Der Schweizer Föderalismus im Wandel‘ (issue no 305, IDHEAP 2018) <http://www.andreasladner.ch/dokumente/aufsaetze/Cahier_Ladner_Mathys_305.pdf>

—— Soguel N, Emery Y, Weerts S and Nahrath S (eds), Swiss Public Administration: Making the State Work Successfully (Palgrave Macmillan 2019)

Linder W, Swiss Democracy, Possible Solutions to Conflict in Multicultural Societies (3rd edn, revised and updated, Palgrave Macmillan 2010)

—— and Mueller S, Schweizerische Demokratie, Institutionen, Prozesse, Perspektiven (4th edn, Haupt Verlag 2017)

Micotti S and Bützer M, ‘La démocratie communale en Suisse : vue générale, institutions et expériences dans les villes 1990-2000‘ (C2D Working Papers Series R08, UZH Centre for Democracy Studies Aarau 2003)

Seiler H, ‘Gemeinden im schweizerischen Staatsrecht‘ in Daniel Thürer, Jean-François Aubert and Jörg P Müller (eds), Verfassungsrecht der Schweiz (Schulthess 2001)

Steiner R, ‘The causes, spread and effects of intermunicipal cooperation and municipal mergers in Switzerland‘ (2003) 5 Public Management Review 551

Tschannen P, Müller M and Zimmerli U, Allgemeines Verwaltungsrecht (4th edn, Stämpfli Verlag 2014)

People’s Participation in Local Decision-Making in Switzerland: An Introduction

Erika Schläppi and Kelly Bishop, Ximpulse GmbH

The Swiss federal system is characterized by a strong orientation towards power sharing, concordance and compromise. Participation is seen as a means of integrating a diversity of views in decision-making, thus contributing to making state authorities at all levels accountable and responsive to its citizens, improving the quality of decisions taken and mitigating possible resistance, deepening legitimacy and credibility of State authorities, and managing conflicts and tensions between various groups.

To make participation effective, people need political space as well as access to information. The freedom of expression and information is guaranteed by the Swiss constitution (Article 16 of the Constitution). While citizens use various channels to inform and express their opinions, the media is a key contributor in forming an open public debate and serves as an important platform for information sharing and ensuring transparency (Article 17 of the Constitution). The Federal Act on Freedom of Information in the Administration seeks to promote transparency with regard to the mandate, organization and activities of the administration and grants the public access to official documents and information (Article 1 Freedom of Information Act). On cantonal and municipal levels there are similar laws and regulations.

The right to participation in political decision-making is a key feature of the Swiss federal system at all levels. The Swiss Constitution guarantees political rights including the ‘freedom of the citizen to form an opinion and to give genuine expression to his or her will’ for all levels (Article 34(2) of the Constitution, Article 136 of the Constitution). The exercise of political rights is regulated at federal level for federal matters only (Article 39(1) of the Constitution) while the cantons regulate their exercise at cantonal and municipal level. In the framework of cantonal law, municipalities enjoy ‘autonomy’ (Article 50 of the Constitution) which in principle includes the way how political processes in the municipalities are organized. In the 26 cantons laws and regulations differ in terms of space left to municipalities to design their own participatory approaches. Formal participation rights are usually reserved for Swiss citizens who are resident in the community at stake (political domicile) (Article 39(2) of the Constitution).

In the Swiss semi-direct democracy, the elected (representative) parliaments and (cantonal and local) governments are coupled with elements of direct democracy. The main instruments of popular participation include the following:

The popular initiative is a powerful tool for citizens, political parties and interest groups to influence the political agenda: At the federal level a constitutional amendment can be demanded with the signature of 100,000 Swiss citizens (see Articles 138ff of the Constitution). When an initiative is disposed, it is discussed by the government and the parliament. They take formal positions on the initiative, which may involve an alternative proposition. Initiatives and counter-proposals must then be submitted to the popular vote. At cantonal and local level, the popular initiative can be used to propose laws and acts as well. The process that leads to popular votes varies among the cantons and municipalities.

Mandatory and optional referenda: At federal level, parliamentary decisions on amending the Federal Constitution, accessing organizations for collective security or supranational communities, and extra-constitutional emergency federal acts must be put to the popular vote (mandatory referendum, Article 140 of the Constitution). With the signature of 50,000 citizens or by the request of 8 (out of 26) cantons, new federal legislation or amendments to legislation can be called for a referendum (Article 141 of the Constitution). At cantonal level, the referenda systems are diverse and often include important administrative acts (such as important decisions on financial expenses, budgets, etc.). At municipal level, what is put to vote, depends on the municipal statute decided by the municipality. The instrument of referendum broadly impacts on the way how political decisions are taken: Swiss authorities at all levels often tend to seek broad majorities for their decisions to avoid a vote.

In smaller rural municipalities (particularly in the German speaking area) main decisions are often taken in citizen’s assemblies where all residents of the respective municipality who are Swiss citizens can participate. In conformity with the cantonal law and municipal statutes, the assembly takes legislative, administrative and financial decisions that are mostly submitted by the municipal executive. In other (bigger and urban) municipalities, a municipal parliament is representing the citizens, mostly complemented with a referendum system allowing citizens for direct impact.

Various types of formal and informal consultation processes ensure that the different views of stakeholders are taken to account from the beginning and integrated into political processes – often to mitigate the risk of a referendum that may skip the final decision in the end. At federal level, the government is obliged to invite the cantons, the political parties and interested groups to ‘express their views when preparing important legislation or other projects of substantial impact as well as in relation to significant international treaties’ (Article 47 of the Constitution). Parallel provisions can be found in the cantonal constitutions. Some federal and cantonal laws and regulations foresee specific consultation procedures in particular domains that affect cantonal and/or municipal decision-making in particular. Municipal consultations refer to many policy fields such as spatial planning, local development strategies, infrastructure projects, environment and energy issues, tourism, traffic issues, or municipal amalgamation processes. Such consultations can take many forms (e.g. hearings, exchange platforms, round tables, information campaigns, etc.). They may target the broad public or specific groups that are perceived by the authorities as potential supporters or spoilers. Some municipalities have established specific consultation processes that involve neighborhood residents in decision-making when they are particularly affected by the matter at stake. Individual processes are foreseen in many municipalities to incorporate specific stakeholder groups on particular topics (Children and youth, parents, elderly people, non-Swiss residents).

The right to petition is guaranteed by the Swiss Constitution as well as established at cantonal and municipal level.

In general, the new media have changed the ways how people express their opinion, communicate among interest groups and with the authorities. New forms and collaborative methods of participation have developed in recent years that complement more traditional forms of participation, particularly at municipal level. Recent research suggests that the executive is increasingly perceiving participation as a means of improving governability in complex and politically fragmented situations. The often relatively low numbers of citizens that are participating also suggest that these new forms are not broadening but deepening participation by targeting certain citizens and groups that are already engaged in political processes.

All these formal instruments invite stakeholders and citizens to participate but in reality, they may not be accessible for marginalized groups, and many of them formally exclude non-citizens. Individual activists and specific interest groups often invent their own spaces and forms to influence the political agenda and the decision-making processes at all levels (e.g. public manifestations of different kinds, protests and ‘strikes’, media campaigns, citizens’ gatherings). In many cases, these ‘invented’ forms are in one way or another related to more formal instruments such as initiatives and referenda.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation, SR 101

Federal Act on Political Rights (PRA), SR 161.1

Federal Act on the Consultation Procedure (Consultation Procedure Act, CPA), SR 172.061

Federal Regulation on the Consultation Procedure (Verordnung über das Vernehmlassungsverfahren (Vernehmlassungsverordnung, VIV)), SR 172.061.1

Federal Act on Spatial Planning (Spatial Planning Act, SPA), SR 700

Federal Regulation on Spatial Planning (Raumplanungsverordnung (RPV)), SR 700.1

Federal Act on the Protection of Nature and Cultural Heritage (NCHA), SR 451

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Auer A and Holzinger K (eds), Gegenseitige Blicke über die Grenze, Bürgerbeteiligung und direkte Demokratie in Deutschland und der Schweiz (Schulthess 2013)

Iff A and Töpperwien N, ‘Power Sharing: the Swiss Experience: Sharing Democracy’ (2008) 2 Politorbis, Zeitschrift zur Aussenpolitik 37

Kübler D (ed), Demokratie in der Gemeinde: Herausforderungen und mögliche Reformen (Schulthess 2005)

Ladner A, ‘Swiss Confederation’ in Nico Steytler (ed), A Global Dialogue on Federalism: Vol. 6 Local Government and Metropolitan Regions in Federal Systems (McGill University Press 2009)

—— ‘The Organization and Provision of Public Service‘ in Andreas Ladner, Nils Soguel, Yves Emery, Sophie Weerts and Stéphane Nahrath (eds), Swiss Public Administration, Making the State work successfully (Palgrave Macmillan 2019)

Lutz G, ‘The Interaction Between Direct and Representative Democracy in Switzerland’ (2006) 42 Representation 45

—— ‘Switzerland: Citizens’ Initiatives as a Measure to Control the Political Agenda’ in Maija Setälä and Theo Schiller (eds), Citizens’ initiatives in Europe (Palgrave 2012)

Linder W, ‘Direkte Demokratie’ in Wolf Linder, Yannis Papadopoulos, Hanspeter Kriesi, Peter Knoepfel, Ulrich Klöti and Pascal Sciarini (eds), Handbuch der Schweizer Politik (4th edn, NZZ Libro 2006)

Moeckli S, Das politische System der Schweiz verstehen, wie es funktioniert – wer partizipiert – was resultiert (Kaufmännische Lehrmittel Verlag 2017)

Vatter A, Kantonale Demokratien im Vergleich (Leske und Budrich 2002)

—— Das politische System der Schweiz (Nomos 2016)