Elton Stafa, NALAS – Network of Associations of Local Authorities of South-East Europe

Relevance of the Practice

Early childhood education is particularly important for improving the educational and life chances of children, in particular those coming from poor or disadvantaged households while creating pathways to a better and more inclusive and resilient society.

Until 2015 the regulation and financing of early childhood education in Albania was a national responsibility. In 2015 the responsibility for this important function was transferred at the local level and local governments have become exclusively responsible for the regulation, administration and financing of early childhood education, which now constitutes one of their most relevant responsibilities in the social sector. With the decentralization of this function, emerged key policy and financial issues in terms of access to and quality of service across municipalities and therefore also between urban and rural areas. From this perspective, the analysis of this practice is crucial to analyzing the problematic realities connected with the urban-rural divide and interplay.

The practice directly addresses the key questions in report section 2 on local responsibilities, related to social welfare policies. The practice in particular addresses also the issues of adaptation of service provision to changes in the demographic structure of their populations. Additionally, the practice cuts across other report sections, in particular section 3 on local finances and section 4 on local government structure.

Description of the Practice

As of 2015, municipalities are exclusively responsible for the regulation and administration of preschool education in Albania. The Ministry of Education, Sports and Youth (MoESY), does not have anymore any role in the provision of the service, except for the development of education curricula and training of preschool teachers, for which both levels of government are responsible. The Ministry’s deconcentrated branches at the territorial level also do not have anymore any regulatory role as regards preschool education. Their role has been re-dimensioned to monitoring and oversight and collecting statistics. From this perspective, local governments in Albania are fully responsible for regulating and administering early childhood education.

At the local level, the newly decentralized responsibility was followed by a specific earmarked grant from the state budget, calculated by the MoESY, for every municipality, based on the historical costs they have incurred before the function was decentralized. The specific transfers covered only the salaries of teachers and support staff in preschools and was distributed to municipalities on the basis of the currently employed personnel – although this would contradict directly the provisions of the Law on Pre-University Education which calls for a per pupil financing system. No other types of expenditures are financed, despite the real and immediate needs.

Albanian municipalities inherited preschool networks that are physically run down, and which have radically different staffing patterns, pupil/teacher ratios, and enrollment rates – differences that have in turn been compounded by internal migration and falling birthrates. Some municipalities have too many underutilized facilities in rural areas. Others have too few teachers, classrooms, and support staff to serve the children living in their urban cores. Many municipalities face both problems.

The decentralization of preschool education brought to light significant disparities across municipalities. Even prior to its decentralization, preschool education had long been both underfinanced and very unevenly provided across the country as a whole. Before it was decentralized, these problems essentially remained ‘hidden’ within the internal operations of the Albanian State. But when preschool education was made a municipal own-function, these differences –and the insufficient and uneven financial flows behind them – all became painfully visible.

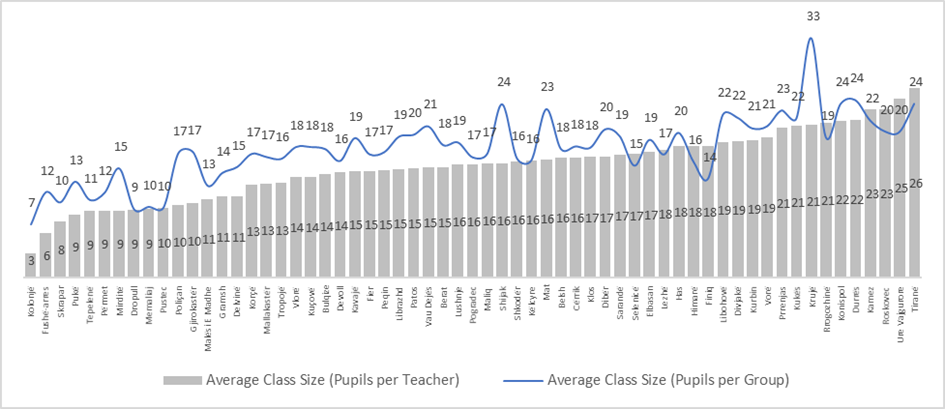

The figure below shows the disparities in terms of average class size in preschool education across Albania’s newly constituted municipalities. It can be noticed that the average class size (pupils per teacher) varies from 3 pupils per teacher in the small and very mountainous Municipality of Kolonje to 26 preschool pupils per teacher in the capital City of Tirana. The figure shows that there are significant disparities across local governments also in terms of number of preschool pupils per group.

This is an indication that the financing system of earmarked specific grants based on the historical costs and decisions of the MoESY, was not reflecting social and demographic developments in Albania and was in fact amplifying the already existing serious inequities across the country.

The Table below shows the breakdown of preschools and pupils between urban and rural areas in 2018. In total in Albania there are 2093 preschools, 27 per cent of which are located in urban settings while 73 per cent in the rural areas. This is a reflection of the fact that the preschools and schools were built during the communist period, when 65 per cent of the country’s population was living in the rural areas, and where there were severe governmental controls over demographic movements from rural to urban areas. Urban preschools host 53 per cent of the total number of preschool children in Albania.

In total, only 10.5 per cent of preschools in Albania provide hot meals for preschool children and charge a daily fee for it of up to EUR 1 per day per pupil. The remaining 89.5 per cent of preschools do not provide any meal for their children. In urban areas, almost all preschools (97 per cent) provide meals for their children while in rural areas only 3 per cent of preschools provide a meal.

| No of Preschools | No Preschool Pupils | No of preschools providing meals | No of preschool children receiving meals | |||||

| Urban | 570 | 27% | 42,940 | 53% | 212 | 97% | 20,875 | 98% |

| Rural | 1,523 | 73% | 37,774 | 47% | 7 | 3% | 396 | 2% |

| Total | 2,093 | 80,714 | 219 | 21,271 |

To begin addressing these challenges and disparities across local governments, in 2019, the Ministry of Finance and Economy and the MoESY, with the support of USAID Albania, adopted a preschool education finance reform. The reform had three main components: (i) improving the legal specification of the financing system for preschool education; (ii) increasing the level of funding for preschool by 10 per cent; and (iii) introducing a new and more transparent and equitable allocation system that is based on the number of pupils as a proxy of service needs and which can be adapted to the social and demographic changes.

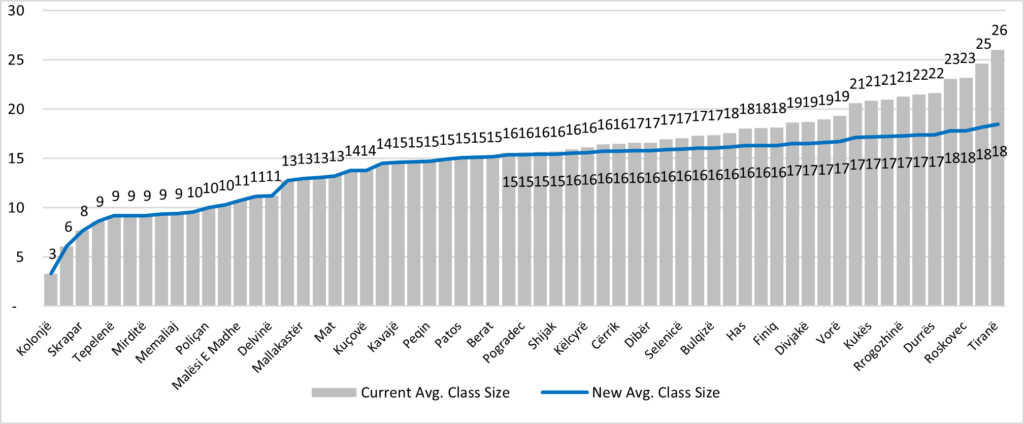

The figure below shows the projected impact of the preschool education finance reform adopted in 2019 in Albania. The increased funding and the new allocation system are expected to push funding towards those municipalities that have an urgent need for additional teachers, measured by their pupil to teacher ratios. It is expected that the reform will result in a general reduction in the average class sizes, from 18 to 15 preschool pupils per teacher and in some extreme cases in both urban and rural areas from 26 to 18 pupils per teacher. The effects of the reforms are expected to resonate in particular in those municipalities that had very overcrowded preschool classes which can be found in both the larger and more urban municipalities such as Tirana, Durres and Kamez but also among smaller and more rural municipalities such as Roskovec and Ura Vajgurore. The figure below shows that if effectively implemented, both small and large, urban and rural, mountainous and non-mountainous municipalities benefit from the new financing system for preschool education.

Ultimately, if effectively implemented, as a result of this program, more than 52,000 (71 per cent) of preschool children will benefit from more comfortable class sizes – a key precondition for improving access to and quality of preschools. This is expected to bring significant improvements in education for Albania’s youngest generations, creating therefore opportunities for a more inclusive and resilient society, while it would also help parents labor market participation.

With the decentralization of the function, the MoFE and the MoESY at the national level in cooperation with local governments and their associations may initiate reform processes to further improve the financing system for preschool education. This is not in breach of local autonomy. Although preschool education has been transformed into a local government function, still, the reformation of the intergovernmental finance system lies within the Ministry of Finance, while the MoESY keeps a monitoring and oversight role.

Assessment of the Practice

Overall, the decentralization of the practice at the local level brought to light major disparities across and within municipalities in terms of radically different staffing patterns, pupil/teacher ratios, and enrollment rates. For about 3 decades radically falling birth rates and massive socio-economic changes fueled high emigration rates and rural-urban migration. These changes decreased the total number of pupils in school while pushing and pulling those who remained to different places. As a result, the existing and already uneven distribution of schools and teachers was knocked further out of alignment with the distribution of pupils.

Before the preschool education was decentralized, these problems essentially remained ‘hidden’ within the internal operations of the Albanian State. But when preschool education was made a municipal own-function, these differences – and the insufficient and uneven financial flows behind them – all became painfully visible. The publication of the funds for each municipality showed the much different treatment of municipalities and showed that actually there was no logic behind the allocation of funds to municipalities, while the law required a per pupil allocation of state budget funds.

However, with the decentralization of preschool education, Albanian municipalities have been increasing spending for education from their own budgets by more than 20 per cent, which indicates that they have taken this responsibility very seriously. The new preschool education finance reform promises to flatten such differences and disparities across municipalities. However, the reform must be effectively implemented and funded. The introduction of a new formula for the allocation of preschool funds, based primarily on pupils, as required by both the Albanian law and international good practice, constitutes a major milestone for creating the preconditions that lead to improved quality and access of preschool education. The new formula is more equitable as it allows for the funding to be adapted to the demographic and immigration and emigration changes – as opposed to the static system based on historical costs. While this reform is an important step ahead, more focus should be given to the ‘quality’ of preschool and pre-university education. The ‘PISA’ standardized tests show that students from rural areas do not perform as well as their peers from urban areas, and this requires additional investments, in particular in the ‘human’ infrastructure. Similarly, the education curricula have to be updated and further developed, in addition to the physical infrastructure of preschools and schools.

However, it is important to highlight that while preschool education is decentralized as an own local function, still local governments continue to face a strong interplay and overlapping between ‘autonomy’ in delivering their responsibilities and ‘supervision’ by higher levels of government. Education in particular is a classical case requiring significant multilevel governance, and therefore there is an even higher need to create systems and mechanisms for an open and inclusive dialogue and coordination across levels of government as opposed to supervision and excessive control.

This practice shows that while progress has been made, additional efforts are needed to support the operation of preschools, in particular in smaller/rural areas and build new ones in highly and newly urbanized areas. Equally importantly, efforts should focus also on building the human capacities at all levels and not only the physical infrastructure.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal documents:

Law no 139/2015 on Local Self-Government (LSGL)

Law no 68/2017 on Local Self-Government Finance (LSGFL)

Government of Albania, ‘National Crosscutting Strategy for Decentralization and Local Government’ (2015)

Government of Albania, ‘Pre-University Education Strategy’ (2016)

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Fuller S and Khamsi GT, ‘Early Childhood Education in Albania at a Glance: ECE Subsector Review’ (Teachers College, Columbia University 2017)

Instat, ‘The 2011 Census in Albania’ (2011) <https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/census/documents/Albania/Albania.pdf>

Levitas A and Stafa E, ‘Early Childhood Education in Albania at the Intersection of Municipal Finance and Governance’ (USAID Albania 2020) <www.plgp.al>

Psacharopuolos G, ‘Albania: The Cost of Underinvestment in Education: And ways to reduce it’ (UNICEF 2017)

Website of the Ministry of Education, Sports and Youth, <https://arsimi.gov.al/>

[1] Data from the Ministry of Education, Sports and Youth and USAID Albania, own calculations

[2] Data from the Ministry of Education, Sports and Youth, own calculations.