Michelle Rufaro Maziwisa, Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape

Relevance of the Practice

This practice deals with integrated development planning which is an intergovernmental process involving all three spheres of government – national, provincial and local. Municipal planning is done through a document called the Integrated Development Plan (IDP). Each municipality is required to prepare and adopt its IDP through a process that allows for public participation and this applies uniformly across urban and rural municipalities.[1] The purpose of the IDP is to prepare a strategy for long-term development of the municipality and align this strategy with the resources available to that municipality and to align local municipality’s development plans with those of the districts within which the local municipality falls, as well as to align the development plans of all three spheres of government. The IDP is particularly important in the context of South Africa because it seeks to advance socio-economic development and achieve transformation at the local level. First, it pays attention to the municipalities that are lagging behind in terms of service delivery; therefore, in this sense the IDP process is important because it places rural municipalities in the limelight as most rural municipalities have infrastructure backlogs. Secondly, the IDP facilitates the fulfilment of constitutional imperatives of the ‘developmental local government’ in terms of Section 152 of the Constitution. It also enables municipalities to ‘structure and manage [their] administration and budgeting and planning processes to give priority to the basic needs of the community, and to promote the social and economic development of the community’ and to ‘participate in national and provincial development programmes’. The IDP thus brings to life the development mandate of local governments as set out in Section 152 of the Constitution, and is especially important in the relationship between a district municipality and the local municipalities within the area of the district.

Additionally, the IDP is a process through which the monitoring and support role of provinces with regard to municipalities is highlighted. Section 154(1) of the Constitution requires the national and provincial governments to ‘support and strengthen the capacity of municipalities to manage their own affairs, to exercise their powers and perform their functions’. Although the province cannot change the municipal IDPs, it is required to provide guidance by submitting comments to the municipalities and the municipalities have an obligation to consider those comments. This is in line with the principles of cooperative governments set out in Section 41 of the Constitution. The IDP process also highlights the supervisory role of provincial and national governments in that the municipalities are obligated to report on their performance to the member of the provincial executive responsible for local government, and submit their reports to the (national) Auditor General. The key legislative instruments are the Constitution and the Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000 (MSA). The White Paper on Local Government, 1998 is the key policy document on the IDP, and it is supported by policies on spatial planning, integrated transport and housing. Practitioners in the field suggest that there is inconsistency and a disconnect between development planning by local, provincial and national government, which undermines national efforts towards coordinated development. This is one of the reasons that support the shift towards a district-led development model (explained in report section 4.4).

What Goes into the IDP?

Section 23 of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000 (MSA) requires municipal planning to be development-oriented. The IDP must contain the municipal council’s long-term vision for ‘critical development and internal transformation needs’. The IDP must align with the provincial and national sectoral plans and all legislation that is binding on municipalities (legislation must be enacted within the functional areas set out in Schedules 4 and 5 of the Constitution). The IDP must also set out the municipality’s spatial development framework together with basic guidelines for the land use management system of the municipality (spatial planning is a crucial issue and is discussed under the preliminary assessment of the practice).

Description of the Practice

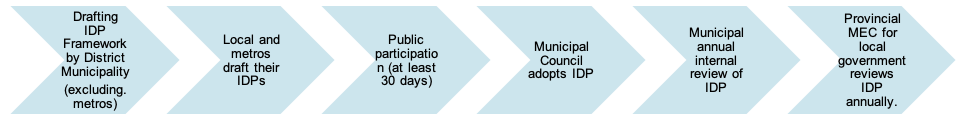

Section 25 MSA sets out the procedure for the adoption of IDPs. First, every municipal council must adopt an IDP for its municipality within the prescribed period. The IDP must link, integrate and coordinate the strategic plans of the municipality, align the strategic plan with resources, constitute the basis of the municipal budget, and align with national and provincial legislation and development plans. If a municipal council is dissolved, the new council may adopt the existing IDP or adopt a new IDP. National and provincial development plans must holistically align with the IDPs and vice versa. It facilitates community participation in the creation of the IDP, and they can use the same IDP to hold the municipality to account. The IDPs are thus political and transformative in their nature. Rural municipalities typically fall within the area of a district municipality, together with other local municipalities, which may be urban or rural. Section 155(1) of the Constitution stipulates that districts have legislative and executive authority in an area that includes more than one municipality and that local municipalities share their executive and legislative authority with the district municipality in whose area they fall under. This is a two-tiered hierarchical relationship between two types of local government, one with more powers than the other.

Process Flow

Politically, the constitutional negotiations of 1993 did not necessarily give local governments much power, but they did set constitutional principles which then led to the entrenched devolution of powers to local government. The IDP came because of significant transformative policy developments at the end of apartheid. The first policy being the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which was the African National Congress’ manifesto in 1994. Its aim was to dismantle the institutional apartheid frameworks to create racially and economically integrated cities (and municipalities). The Development Facilitation Act 67 of 1995 and policy document- Urban Development Framework, 1997 framed the beginnings of development policy for local government. The White Paper on Local Government, 1998 introduced the IDP, and finally placed local governments at the epicentre of development, and provided for development that is integrated not only in terms of persons – i.e. race, but also in terms of accessibility of economic activity and multi-sectoral development planning, across the three spheres of government.

The Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000 which followed, furthered the agenda of the White Paper by placing municipal development needs at the centre, and enabling local governments to be the drivers of local economic development, such that sectoral budgetary allocations should reflect the strategic priority areas of the specific municipality as opposed to sector priorities. However, these local priorities are supposed to not only co-exist, but also be in alignment with the national and provincial priorities and development plans and they must be in line with the principles of cooperative government set out in Section 41 of the Constitution and ‘cooperation’ as required in Section 24 of the Municipal Systems Act. Unfortunately, one of the criticisms of the IDP process is that local and provincial development plans tend to be a cross purposes, and are not often aligned, and that there is no formal IGR structure for consultations on development planning among the three spheres, or even among two, such as between the local and provincial government. Further, Wright argues that South Africa has an ‘overlapping-authority’ model of IGR in which substantial areas of government functions involve all three spheres of government partly due to concurrent powers, there are few areas of independent autonomy, the overarching principles of cooperation and coordination tend to limit the power and influence available to each sphere of government.[2] When development priorities at different levels of government are mismatched, this can create challenges.

The case of Macsand (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town and Others illustrates the divergent priorities of governments at different levels. In this case, Macsand sought to conduct mining operations in terms of a mining permit issued by the national government. However, Macsand did not apply for a local permit to conduct the operations before it began operating. The City of Cape Town then sought an interdict from the High Court of Cape Town to prevent Macsand from mining without a land use permit from the City of Cape Town, and doing so in an area designated by the City as a residential area. The lack of coordination and alignment between the national and local government created legal costs which could have been avoided through consultations ahead of issuing the permit. It also shows that the ‘previous’ hierarchy between the three spheres is still quite visible and often national or provincial government will try to assert their powers over local governments’ development plans. The City of Cape Town is a metropolitan city, with a vibrant economy, well resourced, and raises most of its revenue from own sources. It therefore had the muscle to reject a decision made by the national government that affected a local competence. The situation could have been very different for a rural municipality, with little or no own source revenue, and reliant on transfers from the national government.

The success of the IDP is highly dependent on the collaboration, coordination, cooperation and full participation of each sphere of government, and the meaningful involvement/engagement with local communities (meaning residents, rates payers, civil society organisations and visitors).[3] However, metropolitan cities and urban cities and towns may have more economic or political power than smaller towns and rural areas to assert their local priorities in the face of national and provincial development plans. Moreover, the issue of local government capacity is pervasive as there are often skills and capacity shortages in rural areas to develop the IDP and implement it.

The process of adopting the IDP requires intergovernmental supervision and cooperation. The process is designed to allow on one hand, bottom up community-inclusive local development strategies integrated into provincial and national development strategies, and on the other hand, a top-down monitoring and supervision process. The mechanisms for supervision and cooperation generally apply to urban and rural municipalities in the same manner because the law is framed in terms of the spheres of government and not in terms of categories of local government.

In terms of decision-making, although the municipal council has the responsibility to adopt the IDP, the Member of the (provincial) Executive Committee for Local Government (MEC) has a duty to review the IDP procedurally and substantively at different intervals. The role of the MEC is not to amend the IDP, but to assess the performance of the municipality and compliance with its own IDP by reviewing the key performance indicators, and key performance areas in the IDP and then the MEC can make recommendations. However, in some places, the framing of the law acknowledges asymmetry. For example, provinces are required to take into account the capacity of the municipalities within their province when reviewing municipal IDPs. This implies that an MEC might review a secondary city, which has big budgets and robust economic activity more strictly than a local rural municipality if the MEC takes into account the lack of technical capacity and resources at the rural level.

Assessment of the Practice

Despite this noble approach to planning and gains thus far experienced, several municipalities have struggled with developing meaningful strategic IDPs, and instead many simply have wish lists as opposed to multi-year financial strategies. Success can perhaps be noted from the perspective of municipal staff whose performance is annually reviewed in terms of IDP key performance areas. The IDP improves on the Urban Development Framework because it does not focus on urban municipalities alone; it also applies to rural municipalities. This means rural municipalities have an opportunity to advance and indeed prioritise their own key strategic issues. However, lack of capacity to prepare and implement the IDP continues to be a strain at rural municipalities. Organized local government is not involved in this process. Although the municipal council makes the final decision on the content of the IDP, community members hold the power to influence the content of the IDP through statutory public participation processes. The IDP is theoretically not influenced by the national or provincial government in terms of drafting it. However, because there has to be coherence and alignment across all spheres and across various sectors, the national and provincial spheres do in fact influence or at least set the parameters within which local governments IDPs can be framed. Moreover, rural municipalities have little muscle to push back if national and provincial priorities undermine rural municipality development strategies. For example, in Maccsand (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town and Others (CCT103/11) (CC) [2012], noted above, the City of Cape Town was able to put its foot down on land use planning permits. In the case a mining investor had been granted a mining permit in Cape Town in an area planned for residential use by the local government. The Court held that where the national government grants mining permits (a national competence) this does not do away with the requirement to comply with municipal land use permits, and thus the mining operations by Maccsand (Pty) Ltd could not proceed pending the said municipal permit. It would be very unlikely that a rural municipality in the same situation would have had the same ‘muscle’ to challenge the national government, and the outcome would likely have been different. One of criticisms of the IDP is that there is no formalized IGR structure for provinces and municipalities to engage on IDPs and align their priorities and efforts.[4] This tends to support the calls for a district development model as an alternative which can facilitate coordinated or joint development planning at the district level.[5]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000

Maccsand (Pty) Ltd v City of Cape Town and Others (CCT103/11) (CC) [2012]

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Mbecke P and Mokoena SK, ‘Fixing the Nexus between Intergovernmental Relations and Integrated Development Plans for Socio-Economic Development: Case of South Africa’ (2016) 9(3) African Journal of Public Affairs 99

Steytler N and de Visser J, Local Government Law of South Africa (issue 11, LexisNexis 2018)

[1] See report section 6.3. on Municipal Budgeting and Planning during Covid-19.

[2] P Mbecke and SK Mokoena, ‘Fixing the Nexus between Intergovernmental Relations and Integrated Development Plans for Socio-Economic Development: Case of South Africa’ (2016) 9(3) African Journal of Public Affairs 99.

[3] ibid.

[4] Mbecke and Mokoena, ‘Fixing the Nexus between Intergovernmental Relations and Integrated Development Plans for Socio-Economic Development’, above.

[5] See report section 4.4. on a District Coordinated Development Model.