Kriemhild Büchel Kapeller, Büro für Freiwilliges Engagement und Beteiligung/Amt der Vorarlberger Landesregierung

Relevance of the Practice

Both participation projects aim at involving both citizens in general and vulnerable groups in a more approachable democratic way. Thereby the gap (parallel worlds) between politics and administration and the reality of citizens’ lives should be reduced in the long term and the citizens’ personal responsibility and degree of self-organization (‘less consumerism/consumer behavior towards politics and administration’) should be strengthened. At the same time, new solutions (mainly social innovations) will emerge through the diversity of participants (swarm intelligence and ‘thinking outside the box’). These objectives are based on the long-term experiences with participatory processes in the Land Vorarlberg and coincide with the impacts that the Office for Voluntary Engagement and Participation of the Land Vorarlberg wants to achieve with local and regional participatory processes. In the case of the Bürgerräte (citizens’ councils), practice shows no urban-rural divide in application, while the ‘Lebenswert leben’ or ‘zämma leaba’ (living together) project by Langenegg and Götzis had to be broken down to local districts (quarters or allotments/parcels) for effective implementation.

Problematic realities connected with the urban-rural divide and interplay are targeted in particular where topics are discussed that cannot be resolved within administrative borders like climate adaption, mobility, settlement development or the preservation of natural resources. In this context for example the Bürgerräte on mobility in 2018 and on dealing with land and soil in 2017 contributed to improve the urban-rural interplay.

Description of the Practice

Bürgerräte in Vorarlberg

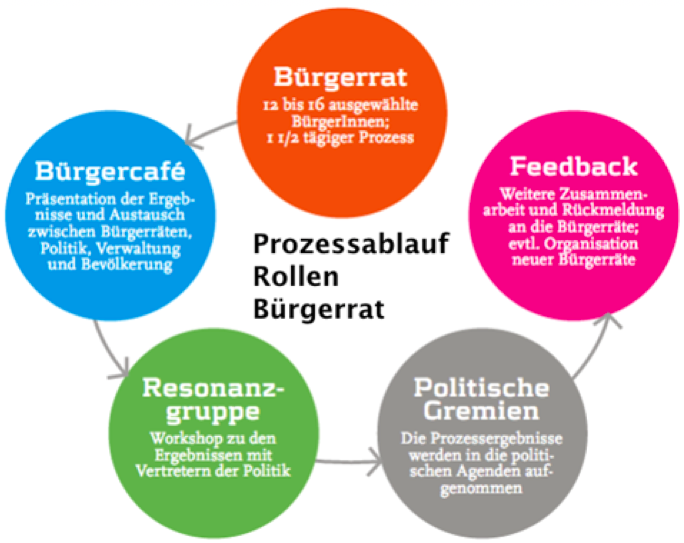

The Bürgerrat is a multi-stage, flexible participation procedure which is usually composed of twelve to fifteen randomly selected citizens. In order to reflect the heterogeneity of society in the citizens’ council, attention is paid to an appropriate distribution of different age groups as well as gender and place of living. ‘The practice of random selection enables a fact-oriented and uninfluenced formation of opinion’, says Prof. Hans J Lietzmann, head of the research center for citizen participation at the University of Wuppertal.[1] Due to the random selection and the absence of any special expertise or qualifications, the participants’ everyday knowledge is put in the foreground. Furthermore, the special moderation technique ‘Dynamic Facilitation’ enables breakthroughs in solution finding.

In order to ensure that the discussion outcomes from the Bürgerräte are taken up, the results from the Bürgerräte are incorporated by the so-called resonance group consisting of representatives from politics and administration (see figure above) into the formal political process and reflects on them. At the Bürgerrat on the topic of ‘Future Agriculture’ for example, which took place in October 2019, the resonance group, consisting of experts from the agricultural sector together with two participants from the Bürgerrat met several times reviewing the results of the Bürgerrat and connecting links with already existing processes, projects and strategies.[3]

Since 2006, more than 40 local and regional Bürgerräte have been held in Vorarlberg and discussed a wide range of topics such as: Living and getting older in Götzis – What is important?; How can the high quality of life in the community be maintained?; What are the most pressing topics in Vorarlberg?; How does a good neighborhood succeed?; How can we implement energy autonomy?; How can we revitalize the city center?; What does a future-oriented education look like?

By anchoring participatory democracy in the Landesverfassung (Constitution of Vorarlberg) in January 2013, a pioneering act in Europe, citizen participation and thus the Bürgerräte were given additional importance. Citizens’ councils following the model of Vorarlberg are primarily also held in Germany (Zukunftsräte), Switzerland and in other Austrian Länder.

Participation Projects ‘Lebenswert leben‘ and ‘zämma leaba’ (Living Together) Langenegg and Götzis

‘Lebenswert leben’ is a long-term project of citizen participation at local and regional level. The aim is to strengthen cooperation between municipalities and to demonstrate the importance of social capital for successful future development. The project started in 1997 and has now been implemented in over 15 municipalities. Both the Großes Walsertal biosphere park and the Bregenzerwälder local government (LG) of Langenegg that have undergone the ‘Lebenswert leben’ or ‘zämma leaba’ process are winners of the European Village Renewal Prize.

More than 50 projects have been implemented so far in both municipalities of Götzis and Langenegg. These include: Citizens’ offices, voluntary transport services for elderly people, ‘Hello neighbor plot parties’, strengthening local supply, repair cafés, etc.[4]

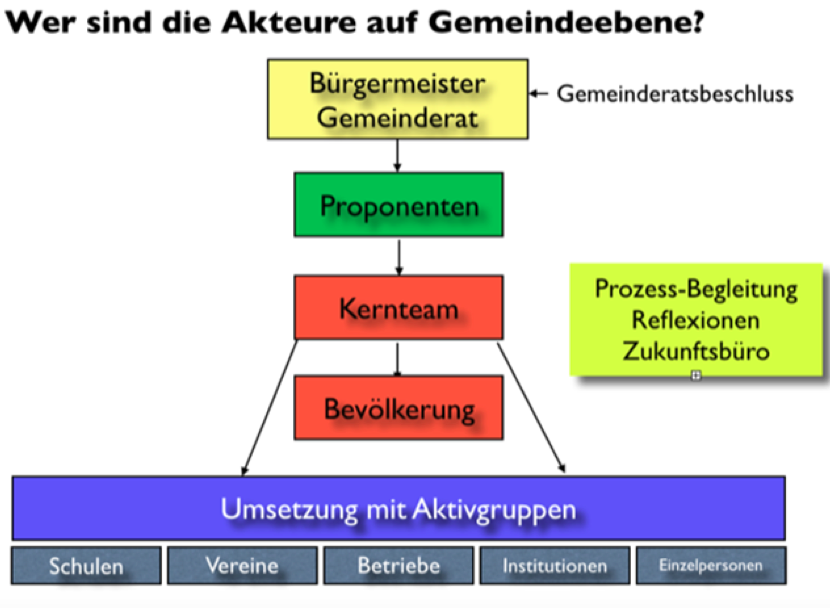

The core team of volunteers plays a key role in the process. It is composed in a way that its members reflect a cross-section of the population (women, men, age distribution: young people to senior citizens, various occupational fields and skills).The selection of the core-team members is made in consultation with so-called ‘opinion leaders’ (usually mayors, municipal clerks, teachers etc., who ‘know’ the people in the community and their talents for welfare) and the process facilitators, who ensure a balanced distribution or composition in the core team and, if necessary, demand this. The task of the core team is to motivate a wide variety of citizens to work and network with local actors, and to thereby establish new collaborations such as between companies and schools, restaurants and clubs, associations with informal initiatives or between neighboring municipalities.

Since the participants choose topics relevant to their own concerns and self-efficacy, they are highly motivated to work out and implement solutions on their own responsibility. The variety of topics include both isolated topics (e.g. using vacancies, individual help for elderly people etc.) – usually carried out in sub-groups – and longer-term issues (e.g. affordable housing, childcare, climate change, etc.). To keep up the motivation for longer-term commitment teambuilding activities and regular reflection in the team (Where do I stand? What are my success experiences? Where are hurdles? Who could support me? What gives meaning to my commitment? etc.) are crucial. In this context an innovative solution was developed in Langenegg: there, the voluntary engagement is limited to two years. After that, a new person ‘automatically’ takes over. This time limit makes it easier to find volunteers. In Götzis, the volunteers could take some time off or ‘rest’ their project if their motivation significantly dropped. Also working on a topic in teams cushions possible motivation loss. To maintain motivation both the recognition and appreciation by the municipality (politics) and – if projects cannot be implemented – clear explanation and justification is essential. However, often it is possible to realize a project only by reorienting the objectives or at least partial steps which also contributes to keep up the commitment.

The project implementation is carried out by involving different groups active on local level such as schools, companies, associations, institutions or engaged individuals or groups. This not only results in wide impact, it also signals the openness of the process (non-partisanship) and the importance of the topic (sustainability/Enkeltauglichkeit). The link between the volunteers and their projects and politics is the core team. Reporting regularly on the progress of the projects in the meetings of the municipal council is one of the core team’s tasks to create linkage with the overall political process.

To get financial support for the projects, every proposal must include a cost estimation and timeline. If necessary, a request for financial support from the municipality must be submitted by the applicant. Based on the official decision of the municipal council to start the project, municipal budget will be reserved for it in advance. Depending on the topic also funding from the Land (e.g. for a cultural project) can be received additionally. Occasionally also sponsoring from companies supports projects.

Beside supporting the process and coaching, an in-depth evaluation is carried out after a year and a half at the latest. In doing so, the achieved impact and planned projects are ‘played back’ to the municipal council. At the same time, essential learning progress has been generated, both for the core team and the whole municipality.

Assessment of the Practice

Both examples of people’s participation in Vorarlberg demonstrate that citizens’ participation contributes to more inclusive policies and can give a boost to social innovation, no matter if it is applied in urban local governments (ULGs) or rural local governments (RLGs). However, challenges of effective participation processes need to be taken into account to successfully meet the goals of involving citizens in local decision-making.

Strengths:

- the perspective of those affected is targeted;

- challenges are faced holistically and, simultaneously an environment for innovative solutions is created;

- both approaches increase the overall understanding and acceptance of projects and political decisions.

Further strengths relate to connection and identification: the regular meetings over a longer period of time strengthen the social capital, which in turn positively affects both the identification with the location and the innovation potential. Both projects are an expression of a new culture of collaboration since they contribute to bringing civil society engagement into the existing processes of decision-making. To manage differing interests within civil society, the ‘Dynamic Facilitation’ method has proven to be very effective in constructively negotiating controversial issues and points of view with each other.

Balancing the relationship between civil society, politics and administration on the one hand and integrating participatory elements in representative democracy on the other hand are the main objectives. Citizens, politics, administration are ‘acting in concert’ to improve the quality of life and to contribute to a sustainable future both in ULGs and RLGs. Success in both rural and urban areas depends on whether a cooperation between politics and administration and civil society is based on trust and mutual appreciation. If this is lacking voluntary engagement will not be successful. In rural areas, this basis of trust tends to exist more often due to the small scale of the area and the fact that ‘everybody knows everybody’. However, even in rural municipalities deep divides need to be overcome. Therefore, mediation processes are needed beforehand so that people build trust and work towards a common goal.

A final strength relates to the term ‘glocal’: Municipalities and regions are affected by high financial requirements (increasing costs severely limit freely available financial resources) as well as by far-reaching societal changes: demographic change, migration and integration, economic upheavals, weakening of local supplies etc. To address the challenges of globalization and urbanization, such participation projects are about strengthening local and regional realities, i.e. resource-oriented rather than deficit-oriented. Active coexistence and a lively ‘we-feeling’ at the local and regional level create positive impact on education, health, local value creation (local supply), increase the ability to innovate and create individual benefits for everyone. This is demonstrated not only by the activities of the ‘Lebenswert leben’ municipalities but also by the analysis of the Vorarlberger social capital studies.

Weaknesses:

- the participants need to commit themselves for a relatively long period of time. Hence, it might be difficult to recruit participants or to keep them active in the long-term;

- the process can create a feeling of exclusiveness and thus a ‘VIP-effect’ on non-participants;

- since only a selection of citizens is involved, the data collected is not statistically significant.

Participatory processes are not useful if the municipal leaders (politicians as well as the administration) are not ready to take up recommendations and suggestions from the citizens. General concerns about the meaning and the value of citizen’s participation impede successful processes, regardless of whether they are planned to be carried out in urban or rural areas. For this reason, raising awareness in the committees (politics and administration) about the value of participation processes together with clear framework conditions for the participation process in advance is crucial. Participatory processes are moreover not useful if there is no scope for action, or if the results are already fixed in advance; or if municipal elections are due in near future. Due to the election campaigns, projects and to some extent also the people involved can get crushed in party-political wrangling. A ‘neutral’ cooperation across party lines is difficult if not impossible in election times. Also, the responsible politicians often do not want to make any decisions until after the election, so that projects are interrupted for a long time.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Amt der Vorarlberger Landesregierung (ed), ‘Bürgerräte in Vorarlberg. Eine Zwischenbilanz‘ (2014)

Büchel-Kapeller K, ‘“Zämma leaba” (zusammenleben) – Resilienz statt Ohnmacht. Gemeindeprojekte in Vorarlberg erproben die Praxis‘ (eNewsletter Wegweiser Bürgergesellschaft, February 2013)

Büchel-Kapeller K, ‘Zämma leaba – Living together’ (Participation & Sustainable Development in Europe, undated) <https://www.partizipation.at/living-together.html>

Devecchi LU and Haßheider EM (ed), ‘Resiliente Gemeinden in der Modellregion Bodensee: Robust und agil durch Partizipation. Ein Forschungsprojekt gefördert durch die Internationale Bodensee Hochschule IBH (2018-2019)’ (2020)

Jäger E, ‘Unterschiedliche Formen der informellen Bürgerbeteiligung im Bereich der Kommunalverwaltung. Eine Darstellung und Analyse ausgewählter Beteiligungsprozesse zur Erhebung von Erfolgsfaktoren und Ableitung von Empfehlungen für den erfolgreichen Einsatz von Bürgerbeteiligungsverfahren‘ (2011)

Kamlage JH and Fleischer B, ‘Bürgerräte: Bürgerbeteiligung am integrierten Bundesumwelt-programm 2030‘ (European Institute for Public Participation 2014)

Kopf R, ‘Nachhaltige Aktivierung und Förderung von Bürgerschaftlichem Engagement in Gemeinden. Gemeinde Langenegg – eine Fallstudie‘ (AV Akademikerverlag 2014) Oppold D, ‘Partizipative Demokratie in der Praxis: Die „BürgerInnenräte“ in Vorarlberg‘ (BA thesis, Zeppelin University 2012)

[1] Hans J Lietzmann, ‘Bürgergutachten Flächennutzung Breitwiesen/Hammelsbrunnen. Weinheimer Bürgerräte 2012‘ (University of Wuppertal 2012) <https://www.buergerbeteiligung.uni-wuppertal.de/en/buergerbeteiligung/gutachtenwerkstatt-papiere/2011-2016/buergerbeteiligung-2012- weinheim.html> accessed 12 July 2020.

[2] Kriemhild Büchel-Kapeller, own illustration.

[3] For further information and concrete results, see <https://www.buergerrat.net/at/vorarlberg/landesweiter-buergerrat/buergerrat-zukunft-landwirtschaft/>.

[4]For more information on the projects, see <https://hdg-vorarlberg.at/ehrenamt/zaemma-leaba-zgoetzis/projekte-zaemma-leaba/; https://www.langenegg.at/initiativen/>.

[5] Kriemhild Büchel-Kapeller, ‘Zämma leaba – Living together’. (Participation & Sustainable Development in Europe) <https://www.partizipation.at/living-together.html> accessed June 19 2020.