Thabile Chonco, Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape

Relevance of the Practice

Municipalities are obliged to ‘ensure the provision of services to communities in a sustainable manner’, to ‘promote social and economic development’ and to carry out developmental duties in terms of Section 153 of the Constitution.[1] There is a huge demand for municipalities to prioritise economic infrastructure so as to promote economic growth, create employment and reduce poverty. With new growth and plunging traditional municipal revenue sources, there is an increased need for new infrastructure and municipalities are required to find other means to finance the demands for bigger and better infrastructure.[2] One such measure is for municipalities to require contributions towards infrastructure costs as a precondition for the approval of a proposed development, known commonly as development charges.

Description of the Practice

Development charges are not a new revenue source for municipalities.[3] They are existing charges some municipalities have been levying to recover costs incurred when providing infrastructure services, albeit inconsistently, while some municipalities have avoided doing so because of uncertainties and risks.[4] Development charges are also not a municipal tax, unlike property rates and taxes levied under Section 229(1)(b) of the Constitution, but do form part of municipal infrastructure finance instruments.

A development charge is a once-off charge that is levied to recover the actual cost of external infrastructure needed to accommodate the additional impact of new development on a municipality’s existing engineering services. It is meant to cover the costs incurred by a municipality when installing new infrastructure or upgrading existing infrastructure that is needed to service a proposed new development. This charge is levied against the developer as a condition for approving a land development application.

The Municipal Systems Act offers a legal basis for a municipality to recover costs associated with municipal services or functions from third-parties such as developers.[5] On the backdrop of the abovementioned, the National Treasury published, for comment, the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill.[6] The proposed law seeks to address the uncertainties concerning the levying of development charges by municipalities. The bill provides for the uniform regulation of development charges, thus catering for a transparent, consistent and equitable basis on which municipalities may calculate and levy development charges from landowners. Charging development charges, in a standardised, consistent and transparent manner, will enhance the revenue streams for financing strategic municipal infrastructure and give municipalities the opportunity to use development charges to guide municipal planning so as to support urban spatial transformation.

A municipality may levy development charges on the engineering services covered in the definition of engineering services provided in the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA),[7] as well as bulk external engineering services, the provision and operation of which lies with the municipality. These are engineering services that provide water, sewerage, electricity, municipal roads, storm water drainage, gas, and solid waste collection and removal, required for the purpose of land development. The bill permits a municipality to apply to the Minister of Finance for an extension of engineering services to be included in the calculation of development charges. This provides some flexibility for municipalities to levy development charges on other engineering services not set out in SPLUMA. The bBill will have implications for various actors including municipalities, developers/landowners, as well as national and provincial departments, state agencies and state-owned enterprises as described below:

The Municipality

Municipalities will have the power to levy development charges in terms of the bill. Upon receipt of a land development application, a municipality has a choice of whether or not to levy a development charge against the proposed land development.[8] Should a municipality decide to levy a development charge, its decision will now be followed by an adoption of a resolution, by its municipal council, to that effect. Once this resolution is adopted, the municipality will have to comply with the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Act. Where a municipality supports the levying of development charges, it will have to adopt a policy that addresses the methodology for the calculation of various costs; ensures the non-duplication of costs when development charges are calculated; sets out the criteria to be used when development charges are based on municipal engineering service zones; and determines the criteria applicable when a subsidy, reduction or exemption is granted to a developer or certain land developments.[9] The policy must also provide for the methods of payment that may be employed, taking into account the principles of equity, transparency and fairness. Whatever shape or form the policy takes, it must be consistent with the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Act on the levying of development charges.

Once the policy on development charges is adopted, a municipality must adopt and publish by-laws for the implementation of this policy. A differentiated approach of the development charges payable may be used for categories of landowners, land developments and municipal engineering services.[10]

The Developer/Landowner

The developer will be liable to pay development charges as a condition of getting their land development application approved. A national, standardised legislation and policy framework on development charges will ensure that the variables used to calculate development charges are the same across all municipalities, irrespective of whether the municipality is a metropolitan, local or district municipality. The legislation and policy framework will also minimise the confusion experienced by landowners, as landowners will be able to estimate their liabilities and hold municipalities to account for the delivery of required infrastructure. The payment can be made either as a payment in-kind or as a monetary contribution. For the purpose of this practice note, the latter is applicable: As a monetary contribution that must be paid in full prior to the developer exercising the rights approved by the Municipal Planning Tribunal (residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural and various other land-use rights exist for certain properties and areas. For example, if a developer is granted commercial land use rights, they may only use the land for commercial purposes by installing infrastructure and constructing commercial properties according to the land specifications given by the municipality). The developer will not only pay for the infrastructure which they benefit from, but will also be informed on how the costs are determined, as well as the quality and quantity of the infrastructure installed.

National and Provincial Departments, State Agencies and State-Owned Enterprises

In 2007, Eskom began the construction of Medupi power station in Lephalala Local Municipality, Limpopo, in order to meet the growing demand for electricity in South Africa.[11] In the following year, Eskom began the construction of Kusile power station in Witbank, Mpumalanga (eMalahleni Local Municipality), also intended to meet the growing demand for electricity in the country.[12] In 2018, President Cyril Ramaphosa launched a multi-billion rand train manufacturing factory in the City of Ekurhuleni ‘as an essential part of government’s rolling stock fleet renewal programme’ to transform passenger rail services and public transport.[13] These projects are tied to the national sphere of government, as well as a state-owned entity and they require land – municipal land to be specific. These projects also require infrastructure – municipal infrastructure to be specific. The involvement of the national government does not excuse it from abiding by municipal planning laws when building the said infrastructure in the various municipalities mentioned. In light of the above examples, national and provincial departments, state agencies and state-owned enterprises that may not have paid any form of development charges previously will now have to do so. This is to ensure that municipalities are not left sitting with infrastructure costs stemming from projects such as those mentioned above. Also, the fact that the bill has not provided for the subsidisation or exemption of land use applications for government purposes (land use by the national government, provincial government or a municipality to give effect to its governance role),[14] supports the view that national and provincial departments instituting land use applications are not eligible for subsidisation and must cough up development charges.

What Can a Municipality Use the Income from Development Charges for?

Development charges must be spent for the infrastructure for which they are collected. The money received must be used to cover the actual costs associated with the provision of essential engineering service(s) to a proposed land development.[15] National Treasury has advised that development charges should not be used for operating costs or costs associated with repairs, maintenance or rehabilitation of infrastructure, as development charges are limited to capital costs for new infrastructure.[16] As such, development charges must be recorded as a liability in a municipality’s financial statements. Only when the municipality uses the development charges for the provision of external engineering infrastructure, it is then recognised as revenue. Development charges should also not be used to address historical backlogs in service delivery created by the neglect of service provision and apartheid-era inequity.

However, National Treasury has also advised that where a municipality has borrowed to provide infrastructure in advance of a development, development charges can be used to repay this debt.[17] This will reduce the finance charges in rates and tariffs and reduce the cost burden on existing residents.

Assessment of the Practice

As already mentioned above, development charges are not a new municipal revenue source and as such, some municipalities currently have development charges policies in existence. This is because the levying of development charges is a power that is incidental to the municipal planning power already exercised by municipalities. The national government may, therefore, regulate minimum standards, norms and guidelines on the levying of development charges. Due to the fact that the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill is yet to sit in Parliament, it is difficult to assess the practice as the bill has not been passed. This also means the bill cannot override any pre-existing policies or by-laws currently used by municipalities to levy development charges. Once the bill becomes law, municipalities relying on pre-existing policies or by-laws will have to ensure that they comply with the new Act. This section will, therefore, rely on two examples of current municipal development charges policies, one policy being from an urban municipality and the other from a semi-rural municipality, to assess how municipalities presently deal with the levying of development charges.

City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality Draft Development Contributions Policy 2020

City of Johannesburg is a metropolitan municipality situated in Gauteng province. It is the economic hub of South Africa and as such, would naturally attract development, particularly through economic infrastructure. The municipality is also equipped to take on mega developments and has the capacity, skills and knowledge to work with multi-billion rand developments. In June 2020, the City completed its Draft Development Contributions Policy, which aligns in many respects with the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill. The Draft Policy requires ‘the payment of development contributions to cover the costs of municipal external engineering services needed to accommodate increased demand for such infrastructure that arises from intensified land use’. The Draft Policy also permits the use of development charges to pay off loans taken to fund existing infrastructure for a service. Where adequate external engineering services already exist to service a development, the Draft Policy states that the development charges collected may be used to provide infrastructure to support development elsewhere in the municipal area and that the revenue may not be used for other purposes.[18] These ‘other purposes’ are not specified but one would imagine that it refers to the exclusions provided in National Treasury’s Development Charges pamphlet.[19]

With regards to the scope of development contributions, the Draft Policy provides that the City’s development contributions calculations will not include the costs of engineering services provided by other spheres of government or by state-owned entities. For example, the costs of a designated provincial road cannot be included in the calculation but where a development is next to a provincial road, that development will be required to pay a development contribution for use of the municipal road network. Another interesting provision in the Draft Policy states that ‘where a new development straddles the boundary with another municipality, the City may agree with that municipality that a portion of the development charge revenue [be] transferred to that municipality’.[20] Such a provision is great for instances where the neighbouring municipality is not as financially strong as the City and also has less development happening in its area, this way both the primary and neighbouring municipalities would benefit from the development. This, of course, is subject to municipalities working together harmoniously.

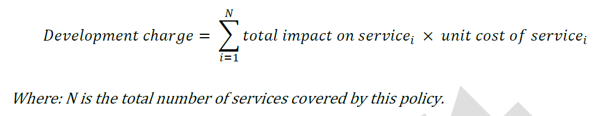

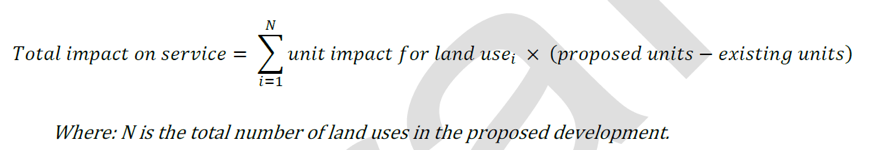

Calculating Development Contributions: the charge for each service is calculated as the total impact of the service, multiplied by the unit cost for that service applicable in the current financial year. The calculation is done for each engineering service covered by the Draft Policy and is done through the following formula:

The total impact that a development will have on demand for municipal bulk services is calculated as follows:

The municipality relies on the proposed land use changes, the unit impact and the unit cost as data inputs to calculate development charges. The policy states that the calculation of development charges is premised on the principles of reasonableness, equity, fairness, predictability, certainty, administrative efficiency and justification, which more or less mimic the principles set out in the bill. So long as the principles can be quantified and justified, then one cannot fault the City for adopting its said formula, absent a standardised formula from the bill and supporting Implementation Guide.

Mogalakwena Local Municipality Draft Development Charges Policy 2020

Mogalakwena Local Municipality is a semi-rural municipality situated in the Waterberg District Municipality in Limpopo province. In December 2020, the City published its Draft Development Charges Policy, which also aligns in many respects with the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill. The Draft Policy states that money collected as development charges must be used for purposes of funding or acquiring capital infrastructure assets in a timely and sufficient manner to support current and projected future land development in the municipal area, and where calculated with reference to a particular impact zone, must be used for capital infrastructure assets in that impact zone. The Draft Policy prohibits the use of development charges as a general revenue source and provides that money collected in respect of development charges may not be used to fund the operating or maintenance costs incurred by the municipality in respect of municipal infrastructure services.[23]

The policy also caters to the semi-rural make-up of the municipality with a provision that addresses the levying of development charges in rural areas/farms.[24] The provision states that development charges will be determined in terms of paragraph 9(1) for buildings or development related to the primary farming activities and can be classified as agricultural industry. This means that the municipality may, of its own accord or if requested by a developer, reduce or increase the amount of bulk services component for a development on a farm or rural area to reflect the actual costs of installation, if exceptional circumstances permit the reduction or increase. Assuming that there will not be significant additional demand on the bulk services on a farm because the workers already working on the farm will continue working in the new buildings, the municipality will levy development charges for any other development on the farm, for example function venues, tourist accommodation facilities, conference facilities or other commercial activities such as wine tasting as these land-uses attract outsiders who place additional demand on the bulk infrastructure.

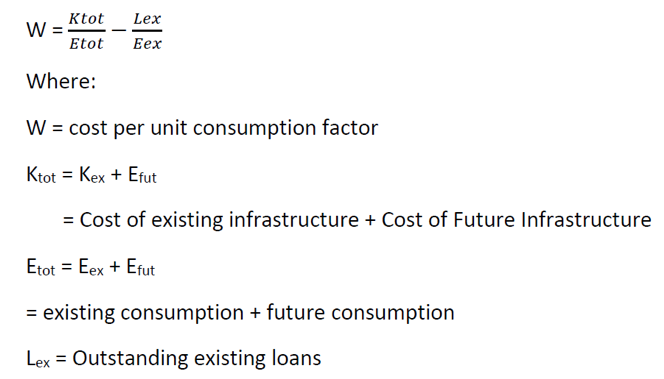

Calculating Development Charges: the municipality relied on available service master plans and future development/town-planning scenarios to develop their formula. The municipality first calculated the cost per unit-consumption of water, sewer, storm water, solid waste, roads and community facilities. The calculation is meant to be an assessment of what to multiply the developer’s required consumption by. Outstanding loans, as well as grants and subsidies given to the municipality were also taken into account to develop the formula.[25]

Similar to City of Johannesburg’s policy, Mogalakwena Local Municipality’s policy states that the calculation of development charges is based on the principles of fairness and equity, predictability, spatial and economic neutrality, and administrative ease and uniformity. Interestingly, annexed to its draft development charges policy is a document titled ‘Development Charge Calculation Report’ where the municipality states the following:

‘[p]reviously DCs were not applicable in Mogalakwena Local Municipality. However, master planning and DC calculations are based on new infrastructure being required for increased usage or consumption of services. Even though a certain area has always had certain zoning rights, it could be that historically the services were designed for an average lesser take-up of those rights, as it was the norm at that time and as such, the original developers did not pay for the new infrastructure required.’

The above paragraph highlights the disparities between semi-rural and urban municipalities. Mogalakwena Local Municipality, unlike City of Johannesburg, previously did not levy development charges but now has a development charges policy because of new infrastructure demands. This means this municipality has much more ground to cover with regards to learning how to levy development charges and also pressuring developers to actually pay as they previously did not and also the municipality was probably one of the ‘friendlier’ municipalities that developers moved to in order to avert paying development charges in the bigger cities.

The following observations can thus be made with regards to the current practice. First, at present, most municipalities’ development charges policies seem to mirror each other, as well as to mirror the Policy Framework for Municipal Development Charges issued by the National Treasury in 2011. This Policy Framework encompassed a broad understanding of the role, purpose and legal nature of development charges across South African municipalities but municipal policies will have to be amended once the act is passed (something the City of Johannesburg has already proactively done) and the guidelines for the implementation of municipal charges become final.

Secondly, until the bill becomes law and National Treasury develops and implements guidelines for the calculation of development charges, municipalities will continue to levy development charges on the basis that they currently do, be it as part of Development Charges policies adopted under Section 75A of the Municipal Systems Act, through municipal planning by-laws or through policies adopted by the council of the municipality concerned. This means a municipality will have wide discretion as to the levying of development charges and, more specifically, the calculation of said development charges, provided that the arrangement is set out in a duly sanctioned policy as shown in the two examples above.

With regards to the bill, the following observations can be made. First, the bill is not too concerned with the type of applicant or the proposed land use, as the principle is that development charges should be calculated for all land use applications so that the infrastructure costs of the development are known irrespective of the municipality levying the development charges or not. Instead, the bill focuses on the impact of the proposed development on infrastructure, and the cost incurred by the municipality in addressing that impact and not on whether the developer should pay for the particular type of land use. If the municipality opts not to levy a development charge, then an alternative source of funding should be identified.

Secondly, although the systematised regulation of development charges should be welcomed, this does not remove the fact that the levying of development charges will remain a complex process. Whereas metros and big cities may be better placed to implement the act, other municipalities may experience challenges in implementing the act. Thus, once the act is enacted, there may be a need for regulations and implementation guidelines that will give more explanation and guidance on the purpose and implementation of development charges. On the other hand, despite all municipalities being asked to implement development charges (with some municipalities doing so and others not doing so), the standardisation of development charges and the calculation therefore raises two issues: the first is the issue of developers who may have decided to move to smaller municipalities to avoid paying development charges and the second issue is that of potentially keeping developers away from smaller, rural municipalities due to a lack of incentives. The first issue is addressed through uniformity presented by the bill, which has the potential to curb the abuse of rural/semi-rural and smaller municipalities, to whom developers would flock in order to escape development charges imposed by bigger municipalities, and provide these municipalities with much needed revenue to provide the necessary infrastructure to support the development. This uniformity, however, lends itself to the second issue pertaining to standardisation across municipalities. Matsie avers that standardisation/uniformity brings to bear the missed ‘opportunity to incentivise developers to develop in smaller or rural municipalities. So even though the revenue is needed in the smaller or rural municipalities, the standardised approach does not attract development and developers, who are already more inclined to develop in urban areas.’ According to Matsie, ‘it would be helpful for the bill to include an approach that regulates development charges in a scale or proportional approach just to give more incentives to developments in rural municipalities’.[27]

Thirdly, in a bid to revive the local economy post the Covid-19 pandemic, and fulfil the obligation to promote social and economic development as required by Section 152(1)(b) of the Constitution, municipalities may be eager to increase economic infrastructure and, thus, approve land development projects subject to levying development charges. Once the bill is enacted, supporting regulations and implementation guidelines may also be helpful in providing certainty on the calculation of development charges. This is necessary to eliminate the negative financial impact municipalities may face when they approve land use applications that do not take sufficient account of the impact of the proposed land developments on the municipal fiscus.

In ending, development charges and the levying thereof is a complex space to navigate. The introduction of a legal framework for the levying of development charges is thus a good starting point as it can be used widely across all municipalities. While the bill goes a long way in providing consistency and uniformity in the levying of development charges, it is clear that metropolitan municipalities, as well as cities will have an upper hand as they have long been levying development charges and are also magnets for development, unlike their rural counterparts.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000

Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act 16 of 2013

Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill of 2020

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Business Insider SA, ‘Municipalities Advised to Consider New Taxes, Including on Parking Lots and Fires’ (Business Insider, 29 July 2020) <https://www.businessinsider.co.za/municipalities-advised-to-consider-new-taxes-including-for-fires-and-entertainment-2020-7> accessed 14 February 2021

City of Johannesburg, ‘Draft Development Contributions Policy’ (2020)

Cole B, ‘Anger Over New Metro Charges’ (IOL News, 15 November 2011) <https://www.iol.co.za/dailynews/news/anger-over-new-metro-charges-1178498>

Crawford C and Juergensmeyer J, ‘A Comparative Consideration of Development Charges in Cape Town’ (2017) 1 Journal of Comparative Urban Law and Policy <https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=jculp>

Eskom, ‘Kusile Power Station Project’ (Eskom) <https://www.eskom.co.za/Whatweredoing/NewBuild/Pages/Kusile_Power_Station.aspx>

—— ‘Medupi Power Station Project’ (Eskom) <https://www.eskom.co.za/Whatweredoing/NewBuild/MedupiPowerStation/Pages/Medupi_Power_Station_Project.aspx>

Graham N and Berrisford S, ‘Development Charges in South Africa: Current Thinking and Areas of Contestation’ (undated) <http://www.imesa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Paper-1-Development-charges-in-South-Africa-Current-thinking-and-areas-of-contestation-Nick-Graham.pdf>

Mogalakwena Local Municipality, ‘Draft Development Charges Policy’ (2020)

Mthethwa A, ‘Developers Protest Mogale City’s New Bulk Services Plan’ (Daily Maverick, 2 November 2020) <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-11-02-developers-protest-mogale-citys-new-bulk-services-plan/>

National Treasury, ‘Media Statement on the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill’ (National Treasury, 8 January 2020) <http://www.treasury.gov.za/comm_media/press/2020/2020010801%20Media%20Statement-%20%20Municipal%20Fiscal%20Powers%20and%20Functions%20Amendment%20(MFPFA)%20Bill.pdf>

—— ‘Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill’ (National Treasury Development Charges Pamphlet) <http://www.treasury.gov.za/legislation/draft_bills/Development%20Charges%20Pamphlet%20V1.pdf>

President Ramaphosa C, ‘Inauguration Address’ (inauguration of the Dunnottar Train Factory, Ekurhuleni, 25 October 2018) <http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/speeches/address-president-cyril-ramaphosa-inauguration-dunnottar-train-factory%2C-dunnottar%2C>

SA Commercial Prop News – SAPOA, ‘Fictitious Tax on Property Developers’ (SA Commercial Prop News, 30 November 2011) <http://www.sacommercialpropnews.co.za/south-africa-provincial-news/kwazulu-natal/3954-fictitious-tax-on-property-developers.html>

Savage D, ‘Evaluating the Performance of Development Charges in Financing Municipal Infrastructure Investment’ (discussion paper, second draft, 23 March 2009)

South African Cities Network, ‘Assessing the Fiscal Impacts of Development: Study Report’ (National Treasury 2015) <http://sacitiesnetwork.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Fiscal-Impact-of-Development-Report-Final.pdf>

[1] See Secs 152(1)(b) and 153(a) of the Constitution.

[2] See Colin Crawford and Julian Juergensmeyer, ‘A Comparative Consideration of Development Charges in Cape Town’ (2017) 1 Journal of Comparative Urban Law and Policy, 10; South African Cities Network, ‘Assessing the Fiscal Impacts of Development: Study Report’ (National Treasury 2015) <http://sacitiesnetwork.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Fiscal-Impact-of-Development-Report-Final.pdf> accessed 14 February 2021. See also Business Insider SA, ‘Municipalities Advised to Consider New Taxes, Including on Parking Lots and Fires’ (Business Insider, 29 July 2020) <https://www.businessinsider.co.za/municipalities-advised-to-consider-new-taxes-including-for-fires-and-entertainment-2020-7> accessed 14 February 2021.

[3] See Nick Graham and Stephen Berrisford, ‘Development Charges in South Africa: Current Thinking and Areas of Contestation’ (undated) <http://www.imesa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Paper-1-Development-charges-in-South-Africa-Current-thinking-and-areas-of-contestation-Nick-Graham.pdf> accessed 14 February 2021; David Savage, ‘Evaluating the Performance of Development Charges in Financing Municipal Infrastructure Investment’ (discussion paper, second draft, 23 March 2009).

[4] Barbara Cole, ‘Anger Over New Metro Charges’ (IOL News, 15 November 2011) <https://www.iol.co.za/dailynews/news/anger-over-new-metro-charges-1178498> accessed 15 February 2021; Ayanda Mthethwa, ‘Developers Protest Mogale City’s New Bulk Services Plan’ (Daily Maverick, 2 November 2020) <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-11-02-developers-protest-mogale-citys-new-bulk-services-plan/> accessed 16 February 2021; SA Commercial Prop News – SAPOA, ‘Fictitious Tax on Property Developers’ (SA Commercial Prop News, 30 November 2011) <http://www.sacommercialpropnews.co.za/south-africa-provincial-news/kwazulu-natal/3954-fictitious-tax-on-property-developers.html> accessed 15 February 2021.

[5] Sec 75A of the Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000.

[6] The Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill was published, for comment, on 8 January 2020 <http://www.treasury.gov.za/legislation/draft_bills/Draft%20Municipal%20Fiscal%20Powers%20and%20Functions%20Amendment%20Bill%20-%20published%20for%20comment.pdf> accessed 14 February 2021.

[7] Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act 16 of 2013.

[8] Sec 9A(1) of the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill.

[9] Sec 9B of the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill.

[10] Secs 9B and 9D of the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill.

[11] ‘Medupi Power Station Project’ (Eskom) <https://www.eskom.co.za/Whatweredoing/NewBuild/MedupiPowerStation/Pages/Medupi_Power_Station_Project.aspx> accessed 17 February 2021.

[12] ‘Kusile Power Station Project’ (Eskom) <https://www.eskom.co.za/Whatweredoing/NewBuild/Pages/Kusile_Power_Station.aspx> accessed 17 February 2021.

[13] Address by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the inauguration of the Dunnottar Train Factory (Ekurhuleni, 25 October 2018) <http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/speeches/address-president-cyril-ramaphosa-inauguration-dunnottar-train-factory%2C-dunnottar%2C> accessed 16 February 2021.

[14] Proposed Sec 9E read together with Schedule 2 of SPLUMA.

[15] Sec 9A(3) of the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill.

[16] ‘Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill’ (National Treasury Development Charges Pamphlet) <http://www.treasury.gov.za/legislation/draft_bills/Development%20Charges%20Pamphlet%20V1.pdf> accessed 16 February 2021.

[17] National Treasury, ‘Media Statement on the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill’ (National Treasury, 8 January 2020) <http://www.treasury.gov.za/comm_media/press/2020/2020010801%20Media%20Statement-%20%20Municipal%20Fiscal%20Powers%20and%20Functions%20Amendment%20(MFPFA)%20Bill.pdf> accessed 16 February 2021.

[18] City of Johannesburg, ‘Draft Development Contributions Policy’ (2020) para 4.2.

[19] See National Treasury, ‘Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Amendment Bill’.

[20] City of Johannesburg, ‘Draft Development Contributions Policy’ (2020) para 7.

[21] ibid para 10(1)(3).

[22] ibid para 10(1)(4).

[23] Mogalakwena Local Municipality, ‘Draft Development Charges Policy’ (2020) para 7.

[24] ibid para 14(2) read with para 9(1).

[25] ibid Annexure A at paras 5(2)-(3).

[26] ibid Annexure A at para 4.

[27] Statement by Rebekah Matsie, Senior Researcher, SALGA (LoGov Country Workshop, Local Financial Arrangements, 2 July 2021).