Viorel Girbu, Congress of Local Authorities from Moldova, NALAS – Network of Associations of Local Authorities of South-East Europe

Relevance of the Practice

Social sector spending accounts for about two-thirds of total public expenditure in Moldova. Aside from spending on social benefits and health insurance, where financial resources are managed through specialized entities that have centrally determined budgets, much social spending is made from the budgets of the first and second-tier Local Public Administrations (LPAs). In 2019, spending on education represented 17.1 per cent of total public expenditure, with 14.8 per cent coming from local government budgets.

Financing social welfare represents a significant part of the total amount of the resources allocated to local budgets, but most of the spending (approx. 80 per cent in 2019) is for education. Mainly spending on education in local budgets is financed from categorical grants allocated by the national government. Majority of spending on education comes from rayon budgets. Nonetheless, 25 per cent of total spending on education comes from cities/commune budgets.

From this perspective, the management and financing of local government responsibilities in education constitute a major part of local government responsibilities and budgets and is therefore at the core of the urban-rural divide and interplay in Moldova. The practice is related to the other report sections in that it addresses issues of financing local authorities and the territorial and administrative organization of local governments.

Description of the Practice

Moldova has two tiers of LPAs, municipalities, cities and communes (first-tier) and Chisinau and Balti municipalities, and rayons (second-tier). The degree of decision-making authority with respect to education functions differs significantly between them. Preschool education is an own responsibility for first-tier LPAs (cities, communes) and is financed from the conditional grants transferred from the central budget, while following tiers of the general education domain are a responsibility of the second-tier LPAs (rayons) and are also financed from conditional grants received from the state budget. Communes play a limited role in education, contributing whatever they can from their limited own revenues and are responsible for the management of the education facilities. The situation with rayons, however, is different. The role of rayons with respect to education is perhaps best characterized as one of being representatives of the national government at the local level: Rayons allocate categorical grants provided by the national government for the provision of the education services at the local level. The management of the institutions responsible for the provision of the general education public services, including preschool units, is appointed by the rayon level authorities. Rayon authorities retain also competencies in the distribution of the conditional grants allocated for the capital investment of the education sector facilities. The mechanism of allocation of the funds for the capital investment required for the development of the facilities in the educational sector is also a tool for the reconfiguration/optimization of the educational sector network of institutions. Localities that reduce the number of educational sector facilities gain more for the investment in the development of remaining educational sector facilities. As such rayons are effectively responsible for ensuring that the policies of central authorities are realized by the organizations (e.g., schools) that provide educational public services at the local level.

The Law on Administrative Decentralization establishes that in education, first-tier LPAs are mainly responsible for the maintenance and development of the physical infrastructure. In this sense, cities and communes are responsible for the construction, management, maintenance and equipping of preschools and extracurricular institutions (nurseries, kindergartens, art schools, music). Rayons – which are significantly larger than communes – are responsible for the management of social affairs of rayon importance at the local level and in particular for education sector. According to the law, second-tier LPAs are responsible for the maintenance of primary schools and primary schools-kindergartens, gymnasiums and high schools, vocational secondary education institutions, boarding schools and boarding schools with special programs, other educational institutions serving the population of the district. They are also responsible for the administration of social assistance units of district interest; the development and management of community social services for socially vulnerable categories; and for monitoring the quality of social services.

Current management of social sector functions at the local level remains influenced by historical practices that differ significantly from the spirit of the Law on Administrative Decentralization. The national government still controls the standard structure and functioning of all schools and educational institutions through framework legislation. Categorical grants for preschool education are provided to local governments on historical patterns and not on any type of per pupil formulas. Historical spending is based on the amount of the spent resources in the previous year adjusted to the inflation rate and relevant changes in the legislation, leading to significant disparities among localities. Introduction of a per child formula could improve efficiency in the usage of the financial resources in this domain and avoid any political interference in the allocation of funds. A per pupil formula, governing the allocation of conditional grants for primary and secondary education, was introduced in 2014.

The main function of the rayon departments concerned with both education and social protection is the implementation of the policy set by the national government. For example, according to the information that can be found on one of rayon’s web page: ‘the Education Department is subordinated to the Ministry of Education in administrative and scientific plan – didactic, and to the district council – in matters of financial and material insurance.’ This sentence reflects the state of decentralization in Moldova: Social sector competences are mainly delegated to rayons whose councils have some authority with respect to the maintenance and improvement of physical infrastructure, but whose functional departments are directly subordinated to the Ministries of education and social protection. As such, rayon governments in the social sector essentially play the role of deconcentrated units of the national government and are fully responsible for managing the grants and transfers provided to them by the national government.

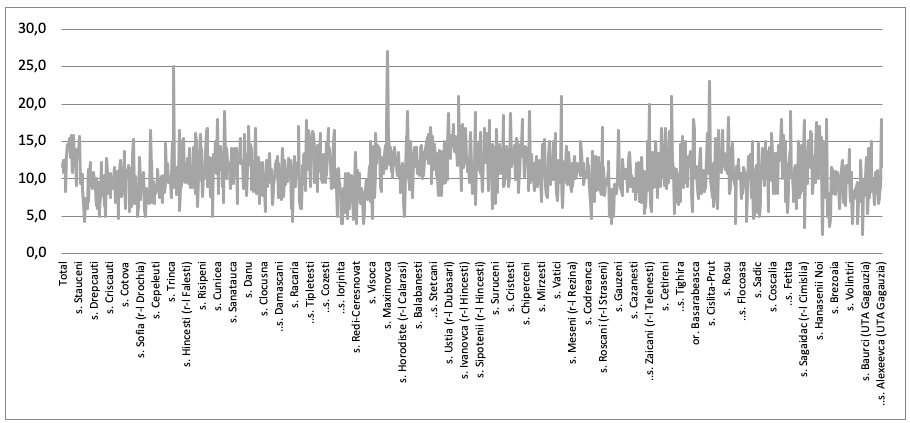

The centralization in the policy promotion in the pre-school education area still does not contribute to homogenization of the provided public services. Despite Moldova has recently adopted a per pupil formula for the allocation of funding for primary and secondary education, still there are significant disparities across the country in terms of access and quality of education and specifically in the preschool education sector. These disparities are further exacerbated by strong demographic changes and social and economic developments of the past three decades across the country leading to different challenges faced by urban and rural localities. For instance, mainly urban localities are characterized by larger class sizes. This is certainly the case in the Chisinau municipality. Urban municipalities are also those who manage the higher amounts of own revenues for the financing of the educational sector. There are wide disparities across the country in terms of staffing patterns and pupil/teachers’ ratios, as shown by the figure above. In 2019, average preschool class size ranged from 2.5 preschool pupils per educator (teacher) to 27 preschool pupils per educator.

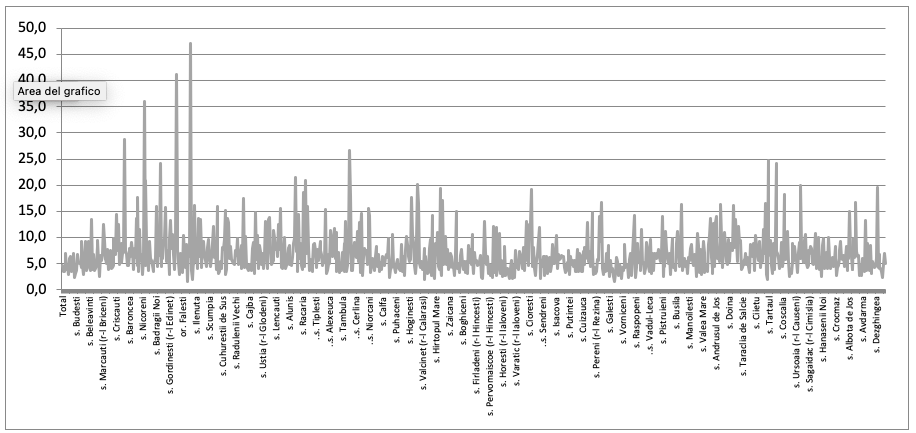

Like in the case of preschool education, there are high disparities among localities across Moldova in terms of classroom surface per student in primary and secondary education, with the indicator ranging from 1.6 m² to 47.1 m² per pupil, as shown in the figure above.

Assessment of the Practice

Despite of the provisions of the framework law on administrative decentralization, decisional and financial autonomy of first-tier LPAs (communes) in education is limited. The content of the relevant secondary legislation follows the historical institutional mechanism in the provision of public services at the local level. This tradition rests on a high level of centralized decision-making. The process of administrative and financial decentralization in Moldova is hindered by the high fragmentation of LPAs and the resulting limited capacity of communes to manage public services in the social domain, specifically in rural localities. Improving the financial autonomy of first-tier LPAs, fostering voluntary amalgamation and enforcing cooperation among them for the final benefit of the citizens is the major precondition in order to achieve progress in the area of decentralization of social sector responsibilities in Moldova.

There are also deficiencies in part related to (the lack of a) clear division of competencies between central and local administration and within the two tiers of local governments themselves. A 2019 report[3] evaluating the education sector in Moldova finds that ‘[t]he mandates of central authorities, local public authorities (LPAs) and educational institutions are not clearly defined, which leads to confusion especially regarding decentralized levels’. The same report finds that ‘there is a high level of inequality between urban and rural areas in terms of access to education’.

The high emigration rate and internal migration, specifically for the rural communities is also exercising a significant influence on the educational sector. Enrolment in schools has decreased significantly in the general education system, but especially in rural schools. Optimization of the school facilities network has a positive effect, but the optimization efforts are outweighed by quick population decline, leading to increasing inefficiencies.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Law no 435/2006 on Administrative Decentralization

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications: UNICEF, ‘Comprehensive Education Sector Analysis’ (2019)

[1] Data from the National Statistics Bureau.

[2] Data from the National Statistics Bureau.

[3] UNICEF, ‘Comprehensive Education Sector Analysis’ (2019).