Partner Institutions: University of the Western Cape, Dullah Omar Institute, and SALGA – South African Local Government Association

The System of Local Government in South Africa

Tinashe Carlton Chigwata, Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape

Types of Local Governments

South Africa has a multilevel system of government organised at national, provincial and local level. There are nine provincial governments while the local sphere of government is constituted by 257 municipalities. The 1996 Constitution of South Africa recognises three categories of municipalities – Category A, B and C.[1] Metropolitan municipalities (Category A) have exclusive municipal executive and legislative authority in their respective areas of jurisdiction. Local municipalities (Category B), which currently total 205, share their municipal executive and legislative authority with district municipalities (Category C) within the relevant area they fall. District municipalities exercise their municipal executive and legislative authority in an area that covers more than one local municipality. These umbrella municipalities (currently 44) were established, among other reasons, to provide support and maximise on economies of scale in areas where there are low capacity municipalities. At policy level, the three broad categories of municipalities (A, B and C) are further broken down into seven sub-categories namely:

- A – metropolitan municipalities;

- B1 – secondary cities, local municipalities with the largest budgets;

- B2 – local municipalities with a large town as core;

- B3 – local municipalities with small towns, with relatively small population and significant proportion of urban population but with no large town as core;

- B4 – local municipalities which are mainly rural with communal tenure and with, at most, one or two small towns in their area;

- C1 – district municipalities which are not water services authorities; and

- C2 – district municipalities which are water services authorities.

National departments often make use of this sub-classification when dealing with municipalities.

The Constitution assigns to local government service delivery responsibilities and a development mandate. It equips local government with a variety of powers – legislative (the power to adopt by-laws), executive, fiscal, budget and administrative powers – to enable the delivery of these responsibilities and obligations. The functional areas of local government are enumerated in Schedule 4 (part B) and Schedule 5 (part B) of the Constitution. These schedules list matters, such as water supply, and electricity reticulation, land use planning, municipal health, local roads, and refuse removal. The principles of subsidiarity and assignment recognised in the Constitution provide opportunities for municipalities to exercise additional functions.

Legal Status of Local Governments

Unlike in many countries, local government is recognised in the Constitution of South Africa as a sphere of government.[2] Thus, the existence of the institution of local government is not dependent on the goodwill of the national and provincial governments. This security of existence is extended to individual municipalities which may not be arbitrarily abolished or merged. Such abolishment or merger can only take place in terms of law and subject to oversight procedures that include the role of an independent body, the Municipal Demarcation Board.

The autonomy of municipalities is constitutionally recognised and can be enforced through the courts. Municipalities have a right to govern their respective areas and this right is only limited by the Constitution. The national and provincial governments may, however, regulate the exercise of this right but subject to limitations imposed by the Constitution. For instance, such regulation mainly takes the form of framework legislation that may not go to the ‘core’ of municipal functions as that is reserved for the legislative authority of municipal councils. National and provincial governments are further prohibited from impeding or compromising a municipality’s ability to exercise this right whether by legislative or other means (Section 151(4) of the Constitution). Thus, it can be observed that unlike in many other countries, the Constitution of South Africa entrenches the existence and autonomy of local government that is jealously guarded by the courts in practice.

(A)Symmetry of the Local Government System

As explained above, there are three categories of municipalities in South Africa – metropolitan, local and district. The Constitution allocates to all metropolitan municipalities equal powers and functions. As opposed to metropolitan municipalities that have exclusive executive and legislative authority in their areas of jurisdiction, legislation and policy defines the division of responsibilities between district and local municipalities. As stated above, within the category of district municipalities there are those that have been designated as water services authorities and those that are not.

The Constitution entrenches the principles of subsidiarity and assignment which if implemented can also result in municipalities within and across categories exercising varying powers. Section 156(4) of the Constitution requires the national and provincial governments to assign to a municipality any of their functions if the function can ‘most effectively be administered locally and the municipality has the capacity to administer it’. This provision is being implemented with respect to some functional areas of the national and provincial governments. For example, metropolitan municipalities, which tend to have significant capacity, are already involved in the delivery of housing even though it is a national and provincial competence. Thus, there is a fair degree of asymmetry in the South African system of local government.

However, the Constitution does not explicitly state that the asymmetry at local level is strictly there to respond to the urban-rural distinction. In practice, nonetheless, district municipalities generally operate in rural and semi-rural areas while metropolitan municipalities and secondary cities (B1) govern in mostly urban areas. Thus, it can be concluded that the local government system is designed in such a way that enables it to respond or adjust to the urban-rural interplay, among other differences present at the local level.

Political and Social Context in South Africa

The ushering of a democratic era in 1994 brought hope to a country that had been ravaged by years of apartheid. Under apartheid, the state, economy and society were organised strictly on the basis of race.[3] The system benefited whites while the majority black population, as well as the minority Indian/Asian and coloured minority groups, were marginalised, deprived of equal economic opportunities and political representation to a different degree, and the former relegated to third class citizens. Since coming to power in 1994, under the leadership of Nelson Mandela, the majority led government of the African National Congress (ANC) has been confronted with a major challenge of undoing or redressing the injustices and legacy of apartheid. A variety of transformation interventions have been adopted in line with the demands of one of the most transformative constitutions in the world, the 1996 Constitution.

These interventions have recorded successes in some areas while failures are common in a number of areas, such as spatial transformation, with apartheid spatial landscape largely remaining intact 27 years after the end of apartheid.[4] Corruption and skills deficit, among other problems, continue to undermine the capability of the state to meet its obligation and development priorities at all levels of government.[5] The slow growth of one of Africa’s largest economies has not made the situation any better. South Africa’s GDP is estimated to grow by merely 1.5, 1,7 and 2,1 per cent in 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively.[6] The unemployment rate, which in the second quarter of 2019 stood at 29 per cent, is another indicator of an economy in trouble.[7] It is thus without doubt that the economy is failing to generate sufficient resources, at a faster rate, for the state to cater for the needs of its estimated 58,78 million population (mid 2019 estimate).[8] This partially explains why poverty remains widespread, inequalities continue to deepen and universal access to basic services remains a dream for many South Africans.

The citizens have been impatient with the ANC government‘s performance in the last few years.[9] The political dominance of the ANC, reflected by, among other things, its two-thirds majority in the National Assembly in the early years of the democratic era, has slowly been eroded. In the 2019 elections, the ruling party won by 56 per cent of the national vote and narrowly won Gauteng province while the opposition, Democratic Alliance, kept its majority in the Western Cape province. At local government level, after the 2016 local government elections, the ruling party is no longer in control of four key metropolitan municipalities. Of the four, one is the legislative capital (City of Cape Town), the other is the administrative capital (Tshwane) while the City of Johannesburg is the economic hub of the country. Some form of coalition governments were formed in Johannesburg, Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay following the failure by any of the political parties to acquire a majority in these municipalities.

The metropolitan regions and cities remain key attraction points for people from rural areas in search for better economic opportunities. By 2017, over 67 per cent of the total population of South Africa was already residing in urban areas, including cities.[10] Consequently, rural areas have been left with a thin base to tap resources such as skilled manpower, a development which undermines their capacity to deliver. On the other hand, the infrastructure in these metropolitan areas is overwhelmed by the large-scale inward emigration and is failing to cope, as a result. For instance, a significant number of the population in these metropolitan regions still resides in informal settlements with no or limited access to basic public services. Even if such services were to be provided, a large portion of people in these areas are not able to pay due to incapacity. Thus, local government, which is positioned at the heart of state public service delivery in South Africa,[11] continues to face a variety of challenges, which are both within and outside of its control.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Constitution of South Africa, 1996

National Treasury, ‘Municipal Budget Circular for the 2019/20 MTREF’ (MFMA Circular no 94, Municipal Finance Management Act No 56 of 2003, May 2019)

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Chigwata TC, De Visser J and Kaywood L, ‘Introduction’ in Tinashe C Chigwata, Jaap de Visser and Lungelwa Kaywood (eds), The Journey to Transform Local Government (Juta 2019)

Ntliziywana P, ‘Professionalisation of Local Government in South Africa’ in Tinashe C Chigwata, Jaap de Visser and Lungelwa Kaywood (eds), The Journey to Transform Local Government (Juta 2019)

Statistics South Africa (2019) <http://www.statssa.gov.za/> accessed 30 July 2019

Steytler N and De Visser J, Local Government Law of South Africa (LexisNexis 2009)

Statista, ‘South Africa: Urbanization from 2009 to 2019’ (Statista, 2020) <https://www.statista.com/statistics/455931/urbanization-in-south-africa/ >

[1] See Sec 155(1) of the Constitution.

[2] See Sec 40(1) of the Constitution.

[3] See Nico Steytler and Jaap de Visser, Local Government Law of South Africa (LexisNexis 2009) 1-3 to 1-9.

[4] Tinashe C Chigwata, Jaap de Visser and Lungelwa Kaywood, ‘Introduction’ in Tinashe C Chigwata, Jaap de Visser and Lungelwa Kaywood (eds), The Journey to Transform Local Government (Juta 2019) 1.

[5] See Patricia Ntliziywana, ‘Professionalisation of Local Government in South Africa’ in Tinashe C Chigwata, Jaap de Visser and Lungelwa Kaywood (eds), The Journey to Transform Local Government (Juta 2019) 59.

[6] National Treasury, ‘Municipal Budget Circular for the 2019/20 MTREF’ (MFMA Circular no 94, Municipal Finance Management Act No 56 of 2003, May 2019) 2.

[7] Statistics South Africa (2019) <http://www.statssa.gov.za/> accessed 30 July 2019.

[8] ibid.

[9] See Ntliziywana, ‘Professionalisation of Local Government in South Africa’, above, 59, 61, 63.

[10] See Statista, ‘South Africa: Urbanization from 2009 to 2019’ (Statista, 2020) <https://www.statista.com/statistics/455931/urbanization-in-south-africa/ > accessed 9 December 2019.

[11] See Steytler and De Visser, Local Government Law of South Africa, above, 1-3.

Local Responsibilities and Public Services in South Africa: An Introduction

Thabile Chonco, Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape

Lungelwa Kaywood, SALGA – South African Local Government Association

Local government is the provider of primary services, which are essential to the dignity of all who live in its area of jurisdiction. Ensuring the sustainable provision of services and encouraging the involvement of communities in the matters of local government are some of the main objects of local government.[1] In this regard, the Constitution calls for municipalities to strive within their financial and administrative capacity to achieve their constitutional mandate set out in Section 152. These objects are crucial in a country that seeks to rectify injustices of the previous apartheid local government- a local government system that deliberately excluded the majority of black citizens from accessing essential services. As such, both urban and rural local municipalities of the democratic local government are responsible mainly for essential services and infrastructure vital to communities’ wellbeing.

The Constitution further sets out the framework for local government responsibilities. Section 156(1) of the Constitution provides that a municipality has executive authority, and the right to administer, the local government matters set out in Schedules 4B and 5B of the Constitution and any other matter assigned to a municipality by national or provincial legislation. Schedules 4B and 5B grant original powers to local government. Local government’s functions must be observed in relation to the developmental mandate given to municipalities by the Constitution (Section 153).

Although at first glance the constitutional provision of local government powers and functions seems symmetrical, Section 156(1)(b),[2] Section 155(3)(c)[3] and the compulsory assignment per Section 156(4)[4] of the Constitution show that there is a system of differentiation of powers and functions.

Division of Functions and Powers Between District and Local Municipalities

The relevant national legislation is the Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998 and it must take into account the need to provide municipal services equitably and sustainably. The constitutional and legislative division of powers and provision of public services is not based on the urban-rural distinction. Legally, metropolitan, district and local municipalities have authority over urban areas. In practice, however, metropolitan and local municipalities govern in mostly urban areas while district municipalities generally govern in rural and semi-rural areas.

Section 83(3) of the Structures Act provides that a district municipality must seek to achieve the integrated, sustainable and equitable social and economic development of its area as a whole.[5] This means that districts are to play a supportive role and must do so by providing the bulk services and district-wide functions set out in Section 84(1) of the Structures Act,[6] and cater for both the district and local municipalities within the district’s jurisdiction. Local municipalities have the powers provided in Sections 156 and 229 of the Constitution,[7] excluding the district powers listed in Section 84(1) of the Structures Act.[8] This division grants local municipalities most day-to-day service delivery functions. The division of powers has not been without problems due to poorly executed mandates as a result of capacity constraints, finances, as well as duplication of services, uneven development and poor relations between the district and local municipalities.

Further, the provision of municipal services must be done in a manner that ensures community participation and accountability. Therefore, integrated development planning (IDP) was introduced through the Municipal Systems Act of 2001 as a key strategic planning instrument for service delivery in local government. The emergence of IDP is strongly linked to the early 1990s drive towards addressing the legacy of apartheid through an integrated and participatory approach to planning.[9] Each municipality prepares an IDP in consultation and cooperation with the local community and other organs of state.[10] This is in realisation of the fact that some municipal services must be delivered in a coordinated manner, for example, when planning for human settlement (housing), other related essential services such as roads, water, and electricity, waste removal, streetlights, public transport, and municipal health services must also be considered. Twenty-five years post-democracy, access to these municipal services has been expanded to previously marginalised communities. However, secondary data suggests an increasing trend of community protests in South Africa since the year 2010, with the highest manifesting in the Gauteng province, a province that is mainly comprised of urban local government (ULG) and deemed to be the economic hub. The reality is that of a local government battling to meet the communities’ expectations as communities often exhibit signs of anger and dissatisfaction with the quality and quantity of services offered by the local government sphere. Based on the Constitution, the communities’ expectations for municipal services are legitimate.

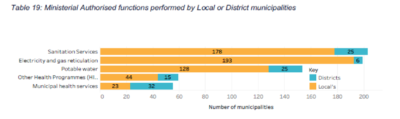

The Structures Act, on the other hand, provides a framework for authorisations and adjustments of functions between the district and local municipalities. The Minister of Local Government may authorise a local municipality to perform or exercise a power in respect of the water, electricity, sanitation and municipal health functions that ordinarily reside with district municipalities.[11] Provincial MECs, on the other hand, are empowered to adjust the powers and functions from a local municipality to a district municipality or vice versa, except for integrated development planning, water, electricity, sanitation and municipal health functions, as well as grants made to district municipalities and collection of taxes or levies in respect of these functions.[12] The adjustment can only take place after a capacity assessment has been undertaken, and the Municipal Demarcation Board endorses the adjustment. Graph 1 shows the number of authorisations that have been made and that a large number of local municipalities are performing functions that are, according to Section 84(1) of the Structures Act, redistributive in nature and are district municipality functions.

Figure 1: Authorisations made by the Minister per Section 84(3) of the Structures Act.[13]

Additional Powers and Functions

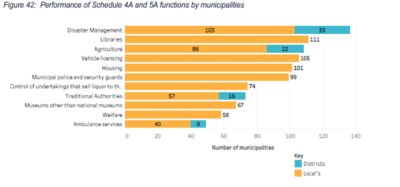

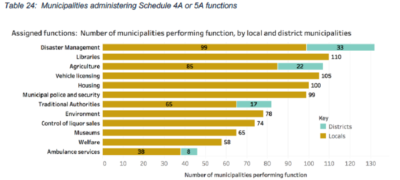

The Constitution mandates the national and provincial government to assign the administration of a Schedule 4A or 5A matter to a municipality if the matter would be most effectively administered locally and the municipality has the capacity to administer the matter (Section 156(4) of the Constitution). A function can be assigned to a specific municipality or to all municipalities in general. An assignment is the secondary source of power for local government. The Constitution (Sections 99, 126 and 156(4)), and the Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000,[14] set out the appropriate procedures for transferring functions to municipalities. The procedures are designed to warrant that the assignment of powers outside of the competencies set out in Schedule 4B and 5B are well placed, that municipalities are protected from unfunded mandates and that legislative and executive capacity is transferred to the assignee municipality.[15] Graphs 2 and 3 below show the Municipal Demarcation Board’s assessment of the number of municipalities performing functions that are originally national and provincial government functions. According to the graphs, a large number of these provincial and national functions are performed by local municipalities.

Figure 2: MDB’s assessment of the number of district and local municipalities that currently perform functions that are not local government’s original functions.[16]

Figure 3: District and local municipalities that currently administer functions that are not local government’s original functions.[17]

Adjustments to Adapt to Changes

Metropolitan municipalities exercise all the original powers of local government enumerated in the Constitution. At present, they cannot adapt their provision of public services to demographic changes in their jurisdiction because there is no framework governing adjustments in metropolitan municipalities. The process of assignment provided in the Constitution could, however, be used to empower municipalities to adapt to changes. For example, municipalities want to perform more housing, public transport and health responsibilities. All these functions fall under Schedules 4A and 5A of the Constitution, making them national and provincial government functions but they could be assigned to municipalities.

Alternative Service Delivery Mechanisms

Municipalities in South Africa have the discretion to use alternative service delivery mechanisms to provide various municipal services that were previously performed internally. The section below outlines two such mechanisms that may be employed.

Use of Municipal Entities as Service Providers

Municipal entities can be established for this purpose.[18] A municipal entity is an ‘organ of state’ and must comply with the legislative framework that applies to its parent municipality to ensure accountability, transparency and consultative processes. Municipal entities are accountable to the municipality or municipalities that established them. The municipal entity enters into a service delivery agreement with its parent municipality and must perform its duties according to the objectives set by the parent municipality. Municipal entities, unlike municipalities, function on business principles and are expected to be free from municipal problems such as inefficiency, slowness and unresponsiveness.[19]

Municipal entities are mainly used by metropolitan municipalities, some district municipalities and some local municipalities that have the capacity. The 2017-18 Auditor General’s Audit Report for Local Government shows that in the 2017-18 financial year, 57 municipal entities were operating across both urban and rural municipalities.[20] This could be due to the scope and variety of services they have to provide, as well as the demographical make-up of the area(s) they have to provide the services in. Key issues to be considered in comparing the performance of entities with that of internal service delivery by the municipality include management capacity, the specific context of the municipality, political and community accountability, and performance monitoring and reporting. While municipal entities cannot be seen as a solution for service delivery, in certain contexts they may be more effective than internal delivery. For example, in the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, the water and sanitation services are provided by the municipal entity Johannesburg Water.[21] In uThungulu District Municipality, the fresh produce market function is performed by the UThungulu Fresh Produce Market.[22]

Contracting with Private Parties

Section 217 of the Constitution states the constitutional framework for procurement by an organ of state in the national, provincial or local sphere of government.[23] When procuring goods and services at a municipal level, Chapter 11 of the Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA) comes into operation and it must be read together with the Preferential Public Policy Framework Act, as well as Chapter 8 of the Municipal Systems Act. Section 111 of the MFMA mandates every municipality and municipal entity to have and implement Supply Chain Management (SCM).[24] The SCM Regulations issued in terms of the MFMA lay down the requirements for the governance of procurement processes. Municipalities have to determine their own procedures and policies, which must be consistent with the legislative framework. If the contract imposes financial obligations on the municipality beyond three years, Section 33 of the MFMA comes into operation and mandates the municipality to consult the local community,[25] National Treasury and the responsible national department if the contract involves the provision of water, sanitation and electricity. Both urban and rural municipalities have to follow this legislative framework when awarding business to private companies.

Municipalities also have the discretion to enter into Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) for the provision of services[26] and infrastructure. This discretion is, however, heavily regulated by the National Treasury and in terms of the Municipal Systems Act.[27] At local government level, PPPs are regulated under the MFMA and its regulations,[28] which provides a framework for municipalities and private sector partners to enter into mutually beneficial commercial transactions, for the public good. PPPs are often used for procuring capital projects and as such the process followed is intensive and requires competitive and transparent bidding, as well as the capacity for the municipality to carry out the projects. While legislation and policy do not differentiate between PPPs for urban or rural areas/government, the procedural requirements of a PPP suggest that a municipality must have the capacity to undertake the strenuous procedure before engaging in the actual substance of the partnership.[29] A PPP has to be strongly motivated, especially with regards to the long term nature of the contract, as well as a municipality’s financial viability before, during and after the PPP has been completed.

One of the PPPs that have improved the lives of the citizens in the City of Tshwane was a partnership between the municipality and the South African Breweries (SAB) in 2018, where SAB rehabilitated two water pump stations – Groenkloof springs and Kentron borehole to increase the municipality’s water supply. The partnership resulted in an additional 7.5 million litres of water for residents per day.[30]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Local Government: Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998

Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000

Local Government: Municipal Finance and Management Act 56 of 2003

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS), ‘Evaluating the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Municipal Entities as Municipal Service Delivery Mechanisms – A Legal Assessment’ (CALS 2010)

City of Johannesburg, ‘City of Johannesburg Annual Report 2017/18’

De Visser J and Christmas A, ‘Reviewing Local Government Functions’ (2007) 9 Local Government Bulletin 13

Du Plessis A (ed), Environmental Law and Local Government in South Africa (Juta 2015)

Kitchin F, ‘Consolidation of Research Conducted on Municipal Entities in South Africa’ (2010)

Makwetu K, ‘Local Government Audit Report 2017/18’ (Auditor General 2019)

Municipal Demarcation Board (MDB), ‘Assessment of Municipal Powers and Function’ (National Report, MDB 2018)

Oxford T, ‘The Success of the Public-Private Partnership’ (Daily Maverick, 26 July 2019).

The South African Breweries (SAB), ‘2025 Sustainability Goals’ (The South African Breweries) <http://www.sab.co.za/post/prosper/working-together-for-water-futures-the-strategic-water-partners-network> accessed 20 January 2020

uThungulu District Municipality, ‘uThungulu District Municipality Annual Report 2017/18’

[1] Sec 152 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, states additional objects of local government as providing for a democratic and accountable government to local communities, promoting social and economic development, and promoting a safe and healthy environment.

[2] Sec 156(1)(b) of the Constitution provides that ‘[a] municipality has executive authority in respect of, and has the right to administer any other matter assigned to it by national and provincial legislation’.

[3] Sec 155(3)(c) of the Constitution provides that ‘[n]ational legislation must subject to Sec 229, make provision for an appropriate division of powers and functions between municipalities when an area has municipalities of both category B and category C. A division of powers and functions between a category B municipality and a category C municipality may differ from the division of powers and functions between another category B municipality and that category C municipality’.

[4] Sec 156(4) of the Constitution states that ‘[t]he national and provincial governments must assign to a municipality, by agreement and subject to any conditions, the administration of a matter listed in Part A of Schedule 4 or Part A of Schedule 5 which necessarily relates to local government, if that matter would most effectively be administered locally and the municipality has the capacity to administer it’.

[5] Act 117 of 1998.

[6] The functions and powers of a district municipality include integrated development planning, portable water supply systems, bulk supply of electricity (transmission, distribution and where applicable, generation), domestic waste-water and sewage disposal systems, solid waste disposal sites, municipal roads, regulation of passenger transport services, municipal airports, municipal health services, firefighting services, fresh produce markets and abattoirs, cemeteries and crematoria, local tourism, municipal public works, grants given to the district (receipt, allocation and if applicable distribution) and taxes, levies and duties (imposition and collection).

[7] These are Schedule 4B and 5B original powers, assigned powers and fiscal powers.

[8] Sec 84(2) of the Structures Act.

[9] Anél du Plessis (ed), Environmental Law and Local Government in South Africa (Juta 2017) 168. For further discussion on the people’s participation, see report section 6 on People’s Participation in Local Decision-Making.

[10] Sec 29 of the Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000.

[11] Sec 84(3) of the Structures Act. The Minister must comply with the consultation requirements set out in this provision.

[12] Sec 85(1) of the Structures Act.

[13] Municipal Demarcation Board (MDB), ‘Assessment of Municipal Powers and Function’ (National Report, MDB 2018).

[14] Secs 10 and 10A of the Municipal Systems Act.

[15] Jaap de Visser and Annette Christmas, ‘Reviewing Local Government Functions’ (2007) 9 Local Government Bulletin 13.

[16] MDB, ‘Assessment of Municipal Powers and Function’, above.

[17] ibid.

[18] Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS), ‘Evaluating the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Municipal Entities as Municipal Service Delivery Mechanisms – A Legal Assessment’ (CALS 2010) 23. The following types of municipal entities are recognised in the Systems Act – private company (subject to restrictions), a service utility (established by a municipality) and a multi-jurisdictional service utility (established by two or more municipalities).

[19] Felicity Kitchin, ‘Consolidation of Research Conducted on Municipal Entities in South Africa’ (2010) 4-5.

[20] Kimi Makwetu, ‘Local Government Audit Report 2017/18’ (Auditor General 2019) Annexure 1.

[21] City of Johannesburg, ‘City of Johannesburg Annual Report 2017/18’ 60-71.

[22] uThungulu District Municipality, ‘uThungulu District Municipality Annual Report 2017/18’.

[23] Sec 217(1) of the Constitution requires the contracting of goods or services to take place in accordance with a system that is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective. Sec 217(3) of the Constitution requires that national legislation prescribe a framework within which the preferential procurement policy referred to in Sec 217(2) must be implemented. The Preferential Public Policy Framework Act (PPPFA) was promulgated as a response to this constitutional imperative.

[24] Sec 112 of the MFMA.

[25] See report section 6 on People’s Participation in Local Decision-Making.

[26] If the PPP involves the provision of a municipal service, chapter 8 of the Systems Act must also be complied with.

[27] See Secs 76-78 and 80-81 of the Municipal Systems Act.

[28] Sec 120 of the MFMA. Read together with the Municipal PPP Regulations (2005), the Local Government SCM Regulations (2005) and National Treasury’s Municipal Services and PPP Guidelines.

[29] See Sec 120(2), (4) and (6) of the MFMA.

[30] ‘2025 Sustainability Goals’ (Greenovation, 16 May 2018) <http://greenovationsa.co.za/2018/05/16/sab-and-ab-inbev-africa-commit-to-2025-sustainability-goals-to-help-grow-local-sa-communities-issues-challenge-to-entrepreneurs-to-solve-sustainability-issues/#:~:text=The%20South%20African%20Breweries%20(SAB,Action%2C%20Circular%20Packaging%20and%20Entrepreneurship.> accessed 20 October 2020. See also Tamsin Oxford, ‘The Success of the Public-Private Partnership’ (Mail & Guardian, 26 July 2019) <https://mg.co.za/article/2019-07-26-00-the-success-of-the-public-private-partnership/>.

Local Financial Arrangements in South Africa: An Introduction

Tinashe Carlton Chigwata, Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape

South Africa has a uniform system of public finance for local government. The framework for local government finance (revenue-raising, expenditure of revenue and financial management) is provided for by the Constitution. The Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act of 2003 (MFMA) is the main piece of legislation that gives effect to this framework. There are also several other pieces of legislation that have been enacted to implement the constitutional framework on municipal finance. This section provides an overview of the sources of revenue for municipalities and the expenditure of revenue.

Taxing Powers

Section 229(1) of the Constitution empowers municipalities to impose property rates and user charges on fees for services provided. In addition, the Constitution permits the national government to decentralise other taxes, levies and duties with the exception of income tax, value-added tax, general sales tax and customs duty. The Municipal Property Rates Act of 2004 and the Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Act of 2007 have been enacted to give effect to the municipal fiscal powers. The latter introduces additional revenue streams for municipalities. In practice, the exploitation of taxing powers varies within and across categories of municipalities. However, a big difference exists between urban and rural municipalities. Urban municipalities, particularly metropolitan municipalities, get most of their revenue from property rates and surcharges on fees for services. Metropolitan municipalities raise about 75 per cent of their budget from their own sources, thus are largely self-financing. On the other hand, rural municipalities, which are often poor, rely heavily on intergovernmental grants for operations. As a sector, local government raises 70 per cent of its own revenue,[1] which is high in comparison to local governments in the region.

Intergovernmental Grants

Various forms of intergovernmental grants complement municipalities’ own sources of revenue. Section 214(1)(a) of the Constitution provides for the equitable sharing of revenue raised nationally among the national, provincial and local spheres of government in each financial year. The allocation takes place through an annual enactment which determines the share of each sphere, provincial government and municipality – the Division of Revenue Act (DORA). The DORA may only be enacted after organised local government (which is the South African Local Government Association – SALGA) and the Finance and Fiscal Commission (FFC) have been consulted and any recommendations of the latter considered. The equitable share is an unconditional grant designed to enable every municipality to provide basic services and perform its constitutional and legislative mandates in its area (Section 227(1)(a) of the Constitution). Its allocation is based on an objective formula that takes into account factors such as population, fiscal capacity and disparities. In addition, metropolitan municipalities also get a share of the general fuel levy as an unconditional grant. Besides these unconditional grants, there are various forms of conditional grants that are allocated to municipalities. Such ‘[c]onditional grant funding targets delivery of national government’s service delivery priorities’ in areas such as infrastructure development.[2]

Borrowing

Section 230A of the Constitution permits municipalities to borrow money to finance current and capital expenditure. Borrowing to finance current expenditure is however restricted for bridging purposes during a fiscal year. These borrowing powers can only be exercised in accordance with national legislation, which is the MFMA. When borrowing money, the Constitution states that a municipal council binds itself and future councils in the exercise of securing loans or investments for the relevant municipality. Section 218(1) of the Constitution provides that the ‘national government, a provincial government or a municipality may guarantee a loan only if the guarantee complies with any conditions set out in national legislation’. In practice, the national and provincial governments are reluctant to guarantee municipal loans. As a result, municipal borrowing largely depends on the creditworthiness of a municipality, which is often determined by the private sector actors. When municipalities borrow from the private sector, they often render their assets and revenue streams as surety. This means that high category municipalities, such as metropolitan municipalities, which tend to have a variety of assets and high fiscal capacity, often exercise borrowing powers relative to poor and often rural municipalities because of their financial position.

Expenditure of Revenue

In general, municipalities have the discretion to spend their own revenue and non-conditional grants. There are, however, rules on how municipalities should spend certain funds. For instance, as stated above, the equitable share is there to finance the delivery of basic services to the poor. Municipalities are also required to budget sufficiently for operating expenditure to avoid having a deficit. The repairs and maintenance budget in each financial year should be at least 8 per cent of the value of property, plant and equipment. The consequence of non-compliance with some of the spending requirements can be severe. The national treasury can, for instance, suspend the transfer of intergovernmental grants to the relevant municipality.[3] Municipal officials, who have key responsibilities in budget formulation and implementation, can also be held individually liable for non-compliance.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Municipal Finance Management Act 56 of 2003

Municipal Property Rates Act 6 of 2004

Municipal Fiscal Powers and Functions Act 12 of 2007

National Treasury, ‘Municipal Budget Circular for the 2019/20 MTREF’ (MFMA Circular no 94, Municipal Finance Management Act No 56 of 2003, May 2019)

The Structure of Local Government in South Africa: An Introduction

Melissa NS Ziswa, Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape

Section 40(1) of the South African Constitution entrenches the three levels of government, namely, national, provincial and local government. The local government as already discussed in South Africa’s report section 2 (local responsibilities) is made up of category A, B and C municipalities. The type of categories is determined by the Municipal Demarcation Board based on the factors set out in Section 155 of the Constitution, and Section 2 of the Municipal Structures Act (MSA). Essentially, areas that comply with the criteria in Section 2 MSA are categorised as metropolitan municipalities and the rest of the country as district and local municipalities.

However, under apartheid, local government institutions were race-based. Racial segregation in South Africa ensured that there were community councils, advisory boards and local authorities appointed for black urban areas. These institutions lacked legitimacy, had little authority, were inadequately funded and often comprised of national government appointees. Black rural areas known as homelands had tribal authorities administering local government matters. Indian and coloured communities were governed by separate local government structures that were subordinate to the national and provincial governments. Lastly, fully-fledged local authorities governed exclusively white communities or areas. Apartheid aimed to limit the extent to which affluent white local municipalities would have to shoulder the financial burden for servicing the disadvantaged black communities. Therefore, when South Africa became a democracy there was dire need to integrate these fragmented local institutions. The amalgamation of municipalities was inevitable to achieve non-racial municipalities.

The main reasons behind the amalgamations between 1994 and 2000 were to integrate racially based local government institutions. However, after 2000, amalgamations were done mainly to ensure the financial viability of municipalities. The Municipal Demarcation Act provides the legal framework for the amalgamation of municipalities. This Act provides a firm guideline as to how amalgamations are planned and implemented. This section will elaborate more on how the amalgamation of municipalities is planned and implemented in the thematic practice below.

The three categories of local government (category A, B and C), are metropolitan municipalities (single-tier), district municipalities and local municipalities (multi-tier). South Africa has eight metropolitan municipalities. On one hand, metropolitan municipalities are stand-alone or single-tiered municipalities with a single council at the helm. The metropolitan council executes all the functions of local government for a city or conurbation. On the other hand, district municipalities comprise of two or more local municipalities. While some local municipalities are secondary cities, or small towns, other local municipalities are rural. The local municipalities are represented on the district municipal council. District municipalities act as umbrella entities over local municipalities giving local municipalities support and assisting with coordination, planning and service delivery. This setup enables coordinated governance throughout the country.

In order to bring urban government closer to the people and improve service delivery, there are ward committees in all local municipalities and metropolitan municipalities. Section 72 (1) of the Structures Act establishes a legal framework for ward committees. The primary objective of ward committees is to enhance participatory democracy. Functions of the ward committee include making recommendations on matters affecting the ward to the ward councillor, through the ward councillor, to the metro or local council, the executive committee, the executive mayor or the relevant metropolitan subcouncil. Therefore, the ward committee serves as a formal communication channel between the ward community and the council and its political structures. Subcouncils in metropolitan areas also serve the purpose of bringing urban governance closer to the people. However, in terms of the Municipal Structures Act, only certain types of metropolitan municipalities may establish metropolitan subcouncils. To date only Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality has a subcouncil. In order to establish the subcouncil, the municipality must adopt a by-law determining the number of subcouncils that are to be established. In addition to that, the municipality must designate a cluster of adjoining wards to the subcouncil. Among the powers and functions of subcouncils is the ability to make recommendations to the metro council on matters affecting its area. Such functions of subcouncils bring urban government closer to the people thus facilitating improvement in services.

The legal framework for horizontal inter-municipal cooperation is the Intergovernmental Relations Framework Act (IGRFA), which provides for vertical and horizontal intergovernmental relations (report section 4). This Act is a manifestation of Chapter 3 of the Constitution, which discusses co-operative government. Section 16 of the IGRFA provides for the Premier’s Intergovernmental Forum (PIF) to promote and facilitate intergovernmental relations between the province and local governments in the province. In Section 24, the IGRFA also provides for district intergovernmental forums, which facilitate intergovernmental relations between district municipalities and local municipalities within the district. The IGRFA also provides for the establishment of inter-municipality forums in Section 28. These platforms serve as a consultative forum for participating municipalities to discuss and consult each other on matters of mutual interest.

In the South African case, several factors can facilitate or impede effective inter-municipal cooperation. The Gauteng City Region is an example of the challenge in managing large interconnected urbanised spaces that are governed by multiple local government structures. For instance, spatial and institutional fragmentation hampers development in the Gauteng City Region. Government institutions fail to align their programmes and projects, particularly with respect to infrastructure development. In certain instances, subsidies are transferred from the national government to provincial governments. The latter in turn transfer those subsidies to municipalities. Delays and bureaucracy often hinder this, particularly if the provincial political party is different from the local government municipalities. This is also precipitated by the lack of shared vision among the municipalities. Previously when one political party governed both provinces and municipalities, it was possible for intergovernmental disputes to be resolved informally at the political party headquarters. Now with different political parties at the helm, this is no longer possible. On the other hand, legislation such as the National Land Transport Act 5 of 2009 facilitates inter-municipal cooperation. The act allows for the creation of a special purpose authority that brings together national, provincial and municipal transport functions into one jointly controlled entity.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998

National Land Transport Act 5 of 2009

Intergovernmental Relations of Local Governments in South Africa: An Introduction

Michelle Rufaro Maziwisa, Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape

Lungelwa Kaywood, South African Local Government Association

The Intergovernmental Relations Framework Act (IGRFA) establishes lines of communication and provides the institutional framework for interaction between national, provincial, and local spheres of government and all other organs of state.[1] The IGRFA aims to provide certainty, coherence, transparency and stability and to facilitate effective and coherent developmental outcomes as envisaged by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Section 40(1) describes the three spheres of government as ‘distinctive, interdependent and interrelated’. Each sphere has autonomy to make final decisions within its areas of competence and there is a two-way relationship of regulation and oversight in order to be a coherent government.[2] The two main approaches to IGR are supervision and cooperation (Sections 100 and 139 of the Constitution).

Supervision

Section 151(3) of the Constitution stipulates that ‘a municipality has a right to govern, on its own initiative, the local government affairs of its community, subject to national and provincial legislation’. Further, Section 156 (1) grants exclusive legislative and executive authority to pass by-laws and administer local government matters listed in Schedules 4B and 5B, and any matters assigned by national or provincial government. However, National and provincial governments have legislative and executive authority to ensure that local governments perform their functions effectively in relation to matters listed in Schedules 4 and 5 (Sections 156(1) and 155(7) of the Constitution). This includes first, the power to ‘regulate’, which in the context of local government was interpreted by the Constitutional Court in the Habitat as follows: ‘It follows that “regulating” in Section 155(7) means creating norms and guidelines for the exercise of a power or the performance of a function. It does not mean the usurpation of the power or the performance of the function itself. This is because the power of regulation is afforded to national and provincial government in order “to see to the effective performance by municipalities of their functions”. The constitutional scheme does not envisage the province employing appellate power over municipalities’ exercise of their planning functions. This is so even where the zoning, subdivision or land-use permission has province-wide implications.’[3] Secondly, the national and provincial governments ‘monitor’ municipalities, which includes promoting the development of local capacity in order for local governments to perform their functions and to manage their affairs (Section 155(6)(a) of the Constitution).[4] Thirdly, national and provincial governments have powers to ‘intervene’ in municipalities that fail to fulfil their constitutional or legislative obligations. There are four types of interventions: regular, discretionary ‘serious financial problems’, mandatory budgetary interventions, and mandatory ‘financial crisis’ interventions (Section 139 of the Constitution). The Municipal Systems Act (MSA) and Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA) contain further provisions pertaining to the monitoring powers of provincial and national government over local government.[5]

Cooperation

Chapter 3 of the Constitution sets out general values and principles for cooperation such as mutual trust and good faith (Section 41 (1)(h)). All three spheres are required to build friendly relations, assist and support each other, coordinate actions and legislation, adhere to procedures, avoid legal proceedings against each other, and inform and consult each other on matters of common interest (Section 41(1)(h) of the Constitution). IGRFA established IGR forums and institutions that facilitate the realisation of these normative principles, for example, through compulsory IGR procedures such as the Division of Revenue Act which must go through each sphere of government (through participatory processes for local government, and legislative processes for provincial and national government) before it becomes law. Although Section 4 IGRFA stipulates that the objects of the act are to create a coherent government, the act focuses on IGR structures as opposed to principles; hierarchies are embedded in some of the IGR structures and national government is dominant in steering IGR, making IGR an object of the centre, and not a collaboration of equal partners.[6] Further, the principles are normative, and in certain instances, such as in Ngwathe Local Municipality v Eskom Holdings SoC Ltd and Others,[7] perceived failure to implement the principles of cooperation may lead to litigation. In this case, the local Municipality of Ngwathe failed to pay its electricity bill to Eskom, and when Eskom threatened to disconnect the electricity supply, Ngwathe local municipality instituted legal action on the basis that Eskom, as an organ of state, had a legal obligation to respect the functional or institutional integrity of Ngwathe local municipality.

Intergovernmental Forums and Institutions

The IGRFA creates intergovernmental forums, where executives of the three spheres of government meet (Section 41(2) of the Constitution). Deemed as the main coordinating body at national level, the President’s Coordinating Council (PCC) consists of the President, the Deputy President, relevant Ministers in the Presidency, Finance and Public Service respectively, Premiers from each of the nine provinces and a municipal councillor designated by SALGA. The PCC is a consultative forum for the President to raise matters of national interest with provinces and organised local government, to consult them on the implementation of national policy, co-ordination and alignment of priorities, and to discuss strategic priorities inter alia. Because the PCC is hierarchical, it tends to be a forum for the President to tell provinces and municipalities what to do, and to detect failures by provinces and municipalities. This leaves very little room for SALGA to make substantial contributions, and if it does, it is difficult to see these translated into policy reform as the agenda is set by the President in terms of Section 8(1)b IGRFA. However, proposals for the agenda can be submitted to the Minister in the Presidency. The IGRFA requires only one member of SALGA to be in attendance- the municipal councillor. The municipal councillor is selected from among SALGA members (as SALGA is organised local government and represents all municipalities in South Africa). The IGRFA does not specify the frequency of meetings of the PCC, but it simply requires that the PCC meets, at the behest of the President of the Republic (Section 8(1)(a)), to oversee and ensure alignment between the spheres and implementation of national policies and legislation.

Further, each national department has a national IGR forum where Ministers meet with Members of the (Provincial) Executive (MinMECs) and a national councillor from SALGA, provided the subject matter of the specific MinMec deals with a matter assigned to local governments in terms of Schedule 4B or 5B. Section 18 IGRFA stipulates that MinMECs are a consultative forum ‘for’ the relevant cabinet member to facilitate alignment between the national and provincial spheres on topical or sectoral issues. MinMECs are hierarchical and can become ‘instruments of centralised control’ and ‘vehicles of command’.[8] There is also a variation called the Local Government Ministerial and Member of the (provincial) Executive forum (LGMinMEC), which invites local government into joint sessions with the provincial and national executive.[9] The reports of the MinMEC must be submitted to the President’s Coordinating Council. In this way, issues raised by provincial MEC and SALGA will be presented to the President through the PCC.

The Premier’s IGR Forum (PIF) is a horizontal forum for the Premier and mayors of district and metropolitan municipalities. The PIF comprises of the Premier of a specific province, provincial cabinet members, mayors of metropolitan and district municipalities, and a representative of SALGA. Unlike the PCC and MinMECs, the PIF is a forum for the premier ‘and’ local government in the relevant province, and the PIF is inherently and in practice, consultative and egalitarian. One of the crucial ways in which SALGA’s voice can influence law and policy is that the PIF may discuss draft legislation and draft national policies relating to matters that affect provinces and/or local governments. The Premier sets the agenda, and meeting dates, but proposals for the agenda can be submitted to Premier ahead of the PIF. In practice, each province sets its own frequency of meetings, some meeting twice a year and other four times a year or as the need arises.

The District Intergovernmental Forum (DIF) is a forum for the district mayor and local mayors in his/her jurisdiction. Intergovernmental institutions such as the Budget Council (which is part of the finance MinMEC), the Budget Forum of Local Government, the National Council of Provinces and the Financial and Fiscal Commission (FFC) also bring the three spheres of government together.

Organised Local Government

South African Local Government Association (SALGA) and its provincial affiliates are recognised as organised local government and represent all 257 municipalities in the country in terms of the Organised Local Government Act.[10] SALGA plays a crucial role of representing local government in IGR forums.[11] However, SALGA has the difficult task of representing the interests of both urban and rural municipalities, which are often different, and are sometimes at odds with each other. Decision-making at national level in SALGA is done by SALGA’s national executive, elected by the SALGA national conference. SALGA executive committee comprises of the chairperson of SALGA, 3 deputies, 6 additional members, provincial chairpersons of SALGA (ex officio), and the head of the administration (who has no vote) and optionally, three additional members. The meetings of SALGA national executive are once every three months, and when the need arises (clause 12.4.2 SALGA Constitution). The Constitution of SALGA empowers the national executive to make representations to provincial and national government (clause 12.7.5) and to determine the representation of SALGA in all national IGR structures and other national forums and such representatives have power to make decisions in these structures and forums, but they must report back to the national executive quarterly (clause 12.7.14).

At the provincial level, decision-making is done by the SALGA provincial executive committee elected by the provincial members’ assembly. The SALGA provincial executive committee comprises of the Chairperson, three deputies and six additional members (it may co-opt three additional members). Similarly, the SALGA provincial executive committee meets once every three months, and when the need arises. All municipalities in the province must be represented on the provincial executive committee. The SALGA Constitution empowers SALGA provincial executive committee to make representations to provincial government (clause 21.6.3), and to determine SALGA representation in provincial IGR structures and other forums, and such representatives have power to make decisions, but must report back to the provincial executive committee (clause 21.6.2). SALGA engages and lobbies for local government in Parliament through the portfolio committees of National Assembly (NA) (Section 163 of the Constitution). Section 163 of the Constitution enables SALGA to participate in all meetings of the National Council of Provinces (NCOP) Select Committees, NCOP plenary debates, joint sittings of NCOP and NA, NCOP Local Government Week and SALGA can designate 10 councillors to hold part-time seats in the NCOP. Although legislation does not invite SALGA into provincial legislatures, some provincial legislatures accommodate the participation of SALGA.[12] Thus SALGA gives local governments a voice in the NCOP and in some provincial legislatures.

Intergovernmental Relations Mechanisms

There are IGR mechanisms for budgeting, planning and implementation, such as implementation protocols and integrated development planning (IDP). Each municipality is required to develop an IDP in consultation with local communities, and in alignment with national and provincial strategic development plans.[13] The MFMA and the Constitution further regulate intergovernmental fiscal relations (IGFR). SALGA participates in fiscal IGR in its role as organised local government.[14]

Dispute Resolution

There are mechanisms for intergovernmental dispute resolution. Section 41 requires all three spheres of government to take ‘every reasonable effort’ to settle disputes out of court and to use litigation only as a last resort. Furthermore, courts may refer matters back to allow alternative dispute resolution (ADR) through political processes if litigation was instituted prematurely. There are also mechanisms to resolve conflicting legislation in order to ensure coherence in the legislative framework.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000

Municipal Finance and Management Act 56 of 2003

Intergovernmental Relations Framework Act (IGRFA) 13 of 2005

[1] Act 13 of 2005.

[2] Nico Steytler, Yonatan Fessha and Coel Kirkby, ‘Status Quo Report on Intergovernmental Relations Regarding Local Government’ (Community Law Center CAGE Project, now Dullah Omar Institute 2006) <https://dullahomarinstitute.org.za/multilevel-govt/publications/status-quo-report-on-provincial-local-igr.pdf> accessed 30 July 2019.

[3] Nico Steytler and Jaap de Visser, Local Government Law of South Africa (LexisNexis 2018) 5-24 (12A); Minister of Local Government, Environmental Affairs and Development Planning, Western Cape v The Habitat Council and Others; Minister of Local Government, Environmental Affairs and Development Planning, Western Cape v City of Cape Town and Others 2014 (5) BCLR 591 (CC) (Habitat CC) [22].

[4] See also Secs 105 and 106 of the Municipal Systems Act (MSA) 32 of 2000.

[5] MSA Act 32 of 2000; Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA) 56 of 2003.

[6] Nico Steytler; ‘Cooperative and Coercive Models of Intergovernmental Relations: A South African Case Study’ in Thomas J Courchene and others (eds), The Federal Idea: Essays in Honour of Ronald L. Watts (1 ed, Queen’s School of Policy Studies 2011).

[7] [2015] ZAFSHC 104 (28 May 2015).

[8] Nico Steytler, ‘National Cohesion and Intergovernmental Relations in South Africa’ in Nico Steytler and Yash Pal-Ghai (eds), Kenyan-South African Dialogue on Devolution (Juta 2016) 313.

[9] Derek Powell, ‘Constructing a Developmental State in South Africa: The Corporatisation of Intergovernmental Relations’ in Johanne Poirier, Cheryl Saunders and John Kincaid (eds), Intergovernmental Relations in Federal Systems (Oxford University Press 2015) 327.

[10] Act 52 of 1997.

[11] National Treasury: Budget Technical Forum and Winter Budget Forum; Department of Works: Technical and Political MINMEC; Department of Safety and Security: Safety and Security Technical and Political MINMEC.

[12] SALGA, ‘Organised Local Government in Parliament and Provincial Legislatures’ (unpublished paper 2013) 9.

[13] Secs 24 and 26 MSA 32 of 2000; Department of Provincial and Local Government, ‘The Implementation of the Intergovernmental Relations Framework Act: An Inaugural Report 2005/6-2006/7’ (Government of South Africa 2007) 38.

[14] Secs 9 and 10 of the MSA Act 32 of 2000; Sec 35 Public Finance Management Act 1 of 1999.

People’s Participation in Local Decision-Making in South Africa: An Introduction

Henry Paul Gichana, Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape

In South Africa, both representative and participatory forms of democracy are protected at all levels of government. With respect to representative democracy at the local level, local communities have a constitutional right to elect members of municipal councils.[1] Participatory democracy is emphasized in South Africa’s system of local governance and is aimed at ensuring accountability, responsiveness and openness.[2] One of the core constitutional objectives for the establishment of local government is to encourage the involvement of communities and community organisations in matters of local governance (Section 152(1)(e) of the Constitution). Municipal governments are therefore required to develop a governance culture that accommodates both representative and participatory democracy.[3]

With respect to participatory democracy, municipalities have a duty to consult and are required to create conditions for and encourage the involvement of the local community[4] in decision-making regarding the level, quality, range and impact of municipal services as well as the available options for service delivery.[5] To further this, local communities are allowed to take part in: the preparation, implementation and review of municipal integrated development plans (IDPs); strategic decisions relating to the provision of municipal services; the preparation of municipal budgets; the establishment, implementation and review of municipal performance management systems as well as in monitoring and reviewing municipal performance, including the outcomes and impact of such performance.[6]

Additionally, municipal administrations are under an obligation to provide full and accurate information to the local community regarding the level and standard of municipal services they are entitled to receive, the costs involved, their rights and duties as well as the available mechanisms of community participation.[7] Moreover, members of the local community have the right to be informed of decisions taken by the political structures at the local level, which may affect their rights, property and reasonable expectations.[8]

To discharge the above obligation, municipalities are required to establish appropriate mechanisms, processes and procedures to enable the local community to participate in the affairs of the municipality.[9] In this respect, municipalities are allowed to establish subcouncils[10] and ward committees[11] which serve as the main participatory structures at the local level.[12] Also, communications done by municipalities to the local community are required to be done through local or regional newspapers or radio broadcast covering the area of the municipality.[13] Additionally, municipalities are required to establish their own official websites (if affordable) or otherwise provide information for display on an organised local government website sponsored or facilitated by the National Treasury.[14]

In facilitating participation, municipalities are required to take into account the special needs of people who cannot read or write, people with disabilities, women and other disadvantaged groups.[15] When communicating to the local community, municipalities are obligated to take into account language preferences and usage in the municipality as well as other special needs of people who cannot read or write. The Guidelines for Implementing Multilingualism in Local Government issued by the Department of Provincial and Local Government (now called the Department for Cooperative Government and Traditional Affairs) encourage municipal councils, through ward committees to consult local communities in the preparation of a municipal language policy that is then used for purposes of ensuring community participation.[16] This is key in facilitating participation in both rural and urban local governments.

To participate, members of the local community have the right to submit written or oral recommendations, representations and complaints to the political structures at the local government level and to receive prompt responses to them.[17] Municipalities are in return required to provide for: the receipt, processing and consideration of petitions and complaints; notification and public comment procedures; public meetings and hearings by municipal councils and other local political structures; consultative processes with locally recognised community organisations as well as traditional authorities and to also make provision for forums to report back to the local communities.[18] Additionally, the meetings of a municipal council on the municipality’s annual report are required to be open to the public and reasonable time allowed for members of the local community to address the council and for the discussion of any written submissions received from the local community.[19]

To ensure local participatory processes are undertaken, municipalities are required, when submitting a copy of their adopted IDP to the provincial government, to provide a summary of the process followed and a statement that the required process, which includes community participation, has been complied with (also see WP4 on IDP).[20] Where this has not been done, the provincial government is mandated to request the relevant municipal council to comply with the required process and make consequential adjustments to the IDP.[21] However, in practice, this constitutes a weak form of oversight given that the provincial government mainly focuses on alignment with intergovernmental relations issues and less on public participation.

This has given room for a more robust role by the courts in ensuring reasonable public participation through judicial review. In instances where there are allegations of a failure of public involvement, the Constitutional Court in Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others [22]developed a reasonableness test to be applied in determining whether the degree of involvement met the Constitutional requirement for participation.[23] The test outlines a set of general factors for consideration which include: the nature and importance of the decision; efficiency of decision-making in terms of time and expense; intensity of the decision’s impact on the public and whether there was any urgency that informed the decision. Whereas this standard was developed in light of involvement with Parliament and provincial legislatures, Steytler and De Visser argue that ‘a municipality’s efforts at involving the local community must meet the same standard of reasonableness.’[24] Subsequent court decisions such as the case of Borbet South Africa (Pty) Ltd and Others v Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality[25] have actually held that the standard is even higher for municipalities.

Additionally, the courts have been liberal with the question of standing such as to allow community members and community organisations the right to initiate proceedings against local governments on questions of public participation.[26] This was the approach adopted by the court in Stellenbosch Ratepayers’ Association v Stellenbosch Municipality[27] as well as in Mnquma Local Municipality and Another v The Premier of the Eastern Cape and Others.[28] The courts in both cases adopted a broad approach to standing to allow a ratepayers’ association and members of the community respectively to bring cases contesting subnational decisions on the basis of want of public participation.[29]

To facilitate participatory democracy at the local government level, municipalities are allowed to use their resources and to annually allocate funds in their budgets for purposes of ensuring community participation.[30]

When making regulations or issuing guidelines regarding community participation at the local government level, the minister for local government is required to differentiate between different kinds of municipalities according to their respective capacities to comply with the statutory provisions for public participation[31] including making provision for phased application of public participation requirements that have a financial or administrative burden.[32] While this was key in ensuring the accommodation of both urban and rural municipalities by allowing them to undertake participatory processes with due regard to their respective capacities, the provisions are currently equally applicable to all municipalities.[33]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

Local Government: Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998

Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000

Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act 56 of 2003

Borbet South Africa (Pty) Ltd and Others v Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality (3751/2011) [2014] ZAECPEHC 35; 2014 (5) SA 256 (ECP)

Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others (CCT12/05) [2006] ZACC 11; 2006 (12) BCLR 1399 (CC); 2006 (6) SA 416 (CC)

Mnquma Local Municipality and Another v The Premier of the Eastern Cape and Others (231/2009) [2009] ZAECBHC 14 (5 August 2009)

Stellenbosch Ratepayers’ Association v Stellenbosch Municipality [2009] JOL 24616 (WCC) [17]

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Cohen L, ‘Guidelines of Multilingualism in Local Government: Ambitious Rhetoric or a Realisable Goal?’ (2008) 10 Local Government Bulletin

Steytler N and De Visser J, Local Government Law of South Africa (LexisNexis 2016)

[1] Sec 157 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Constitution) as read with Secs 22 and 23 of the Local Government Municipal Structures Act, 1998.

[2] See the concurring judgment of Sachs J in Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others (CCT12/05) [2006] ZACC 11; 2006 (12) BCLR 1399 (CC); 2006 (6) SA 416 (CC) 120 [230].

[3] Sec 16, Local Government Municipal Systems Act (Systems Act).

[4] The Municipal Systems Act (Sec 1) defines a local community as comprising: the residents of the municipality; the ratepayers of the municipality; any civic organisations and non-governmental, private sector or labour organisations or bodies which are involved in local affairs within the municipality; as well as visitors and other people residing outside the municipality who, because of their presence in the municipality, make use of services or facilities provided by the municipality. The act lays special emphasis on the poor and other disadvantaged sections of this body of persons.

[5] Sec 4(2) as read with Sec 16 of the Systems Act.

[6] Sec 16(1)(a), Systems Act.

[7] Sec 6(2)(e) and (f) as read with secs 18 and 95 of the Systems Act.

[8] Sec 5(1), Systems Act.

[9] Sec 17(2), Systems Act.

[10] Subcouncils are made up of those elected councillors representing the wards that constitute the designated area of the municipality as well as an additional number of councillors elected to the municipal council by way of party lists. The latter are appointed by political parties according to their representation in the municipal council. See Sec 63 as read with Schedule 4 of the Municipal Structures Act.

[11] A ward committee is made up of the councillor representing the specific ward and an additional number of not more than ten persons. The latter are elected in accordance with rules laid down by the municipal council and which are aimed at ensuring gender equity as well as the representation of the ward’s diverse interests. See Sec 73 of the Municipal Structures Act.

[12] Sec 7 (d) and (e), Structures Act; Nico Steytler and Jaap De Visser, Local Government Law of South Africa (LexisNexis 2016) 6-12(3) – 6-13.

[13] Sec 21 (1), Systems Act.

[14] Sec 21B, Systems Act.

[15] Sec 17(3), Systems Act.

[16] Leah Cohen, ‘Guidelines of Multilingualism in Local Government: Ambitious Rhetoric or a Realisable Goal?’ (2008) 10 Local Government Bulletin.

[17] Sec 5(1), Systems Act.

[18] Sec 17(2), Systems Act.

[19] Sec 130, Local Government Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA).

[20] Sec 32(1)(a) and (b), Systems Act.

[21] Sec 32(2), Systems Act.

[22] (CCT12/05) [2006] ZACC 11; 2006 (12) BCLR 1399 (CC); 2006 (6) SA 416 (CC) 120.

[23] Steytler and De Visser, Local Government Law of South Africa, above, 6-16.

[24] ibid.

[25] (3751/2011) [2014] ZAECPEHC 35; 2014 (5) SA 256 (ECP) (The Borbet Case).

[26] Steytler and De Visser, Local Government Law of South Africa, above, 6-7.

[27] [2009] JOL 24616 (WCC) [17].

[28] (231/2009) [2009] ZAECBHC 14 (5 August 2009).

[29] Steytler and De Visser, Local Government Law of South Africa, above, 6-7.

[30] Sec 16, Systems Act.

[31] Sec 22(2)(a), Systems Act.

[32] Sec 22, Systems Act.

[33] Steytler and De Visser, Local Government Law of South Africa, above, 6-20.