Partner Institution: KDZ – Centre for Public Administration Research Austria

The System of Local Government in Austria

Dalilah Pichler, KDZ Centre for Public Administration Research Austria

Types of Local Governments

The Austrian Constitution defines Austria as a federal state formed by nine Länder. These are further divided into districts (Bezirke), administrative units executing tasks for both the Länder and the national government, where no statutory city exists. There are, however, 15 statutory cities (Statutarstädte) with a special statute, combining the authority and responsibilities of a municipality and a district. Municipalities (Gemeinden) are granted the right to self-government as independent administrative bodies in their sphere of competence by Article 116 of the Austrian Constitution. In sum, the three relevant levels of government are the central government, Länder and municipal level with some exceptions such as statutory cities which are assigned responsibilities from district level as well as the Capital City of Vienna, which is a municipality and a Land at the same time.

Legal Status of Local Governments

The Austrian Constitution of 1920 entrenches and protects municipalities not only as local administrative units but also as institutions of self-government (Article 116(1)). However, Articles 115–20 of the Constitution also extensively predetermine the organization of municipalities, their powers and intergovernmental relations. This tight national constitutional regime reduces the complementary power of the Länder under Article 115(2) of the Constitution to autonomously regulate local government through their own laws (Gemeindeordnungen) which results in a tendency towards uniformity.

As for their responsibilities, municipalities may only act lawfully on the basis of competences that are expressly conferred upon them and circumscribed by either national or Land legislation. However, this legislation must make them responsible for ‘all matters that exclusively or preponderantly concern the local community’ and are ‘suited to performance by the community within its local boundaries’ (Article 118(2) of the Austrian Constitution). Whether national and Land legislators observe this rule is checked by the Constitutional Court.

The own autonomous competences of municipalities on this basis, which exist in addition to the competences delegated from the national or Land government, include, in particular, the following areas: traffic and transport; gas, water and electricity supply; waste collection; sewage disposal; kindergarten, parts of education; elderly care; cemeteries; and cultural and sport facilities are all within the competences of municipal administration. For providing these public services, municipalities manage their own budget independently and can own assets of all kind and operate economic enterprises. A major share of municipal budgets comes from intragovernmental transfers, which is a complex system of re-distribution of revenues across all levels of government.

(A)Symmetry of the Local Government System

The distribution of powers is uniform for all municipalities and therefore fails to take into account differences between bigger urban and smaller rural local governments. The Austrian Constitution adheres to the ‘principle of the abstract uniform municipality’, as enshrined already in 1920. This means that, with the exceptions of the above-mentioned statutory cities and the capital Vienna,[1] all municipalities enjoy, also regarding their competences, equal legal status irrespective of variations in territorial size, population or economic and administrative capacities.

Performing the same tasks as big municipalities can be challenging for Austria’s smaller municipalities. The latter are the majority, as 55 per cent of 2,096 municipalities (in 2018) have less than 2,000 inhabitants and 88 per cent have less than 5,000 residents. Thus, Article 116(a) of the Austrian Constitution lays down the possibility for inter-municipal cooperation in the form of local authority associations (Gemeindeverband) to manage certain areas of responsibility such as water supply or waste management (single-purpose associations). Since 2011, the founding of multi-purpose associations (Mehrzweckverband) between municipalities is possible in order to go beyond coordination and centralize public service provision such as regional planning, economic development or welfare services. Even though it is legally possible, such multi-purpose associations are not very common.

Another form of cooperation is the possibility of municipalities merging into an institutionalized regional authority, the ‘territorial municipality’ (Gebietsgemeinde), as foreseen by Article 120 of the Constitution. The territorial municipality offers the possibility of bundling and/or controlling as many tasks as possible on a regional level, while at the same time maintaining decentralized provision of services by the individual local communities. The preservation of the local identity is guaranteed by own local mayors and municipal councils. However, this form of territorial merger (as opposed to amalgamations) is considered ‘dead law’, as it has never been put into practice.[2]

Political and Social Context in Austria

The two major parties, the conservative Austrian People’s Party and the Social Democratic Party of Austria have historically shared the parliamentary majority, with the right-wing Austrian Freedom Party ranging on third place with a significant share of votes since the 1990s. Other smaller parties are the Green Party and the liberal NEOS party. All mentioned parties are currently represented in different levels of government with different majorities. On the local level, apart from local independent candidate lists, the majority of municipalities are still split between the People’s Party and the Social Democrats. This is also reflected in the organization of municipal associations, one being the Austrian Association of Municipalities (Gemeindebund), which is typically associated with the conservative party and smaller rural municipalities, and the Austrian Association of Cities and Towns (Städtebund), being organizationally closer to the Social Democrats and representative of larger cities.[3] However, this differentiation should be seen in a more historical context, as many municipalities and cities are members of both associations.

As of 2018, 52 per cent of Austria’s population lived in municipalities with less than 10,000 inhabitants and 48 per cent in only 86 larger towns and cities, with Vienna alone having 21 per cent of the Austrian population.

As in many countries, urban and rural areas in Austria face different social problems and demographic challenges. Regarding poverty and social exclusion, for example, residents of Austria’s urban areas are more at risk than their rural counterparts because of more single parents’ households and more households with no or little income.[4] On the other hand, rural areas are confronted with out-migration especially of young people, women and highly educated people to cities. This has significant long-term effects on economic development, as well as the provision of health care and elderly care services.[5]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Legal Documents:

Austrian Federal Constitution (B-VG, Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz), BGBl. No 1/1930 (WV) idF BGBl. I no 194/1999 (DFB)

Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications:

Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Nachhaltigkeit und Wasserwirtschaft, ‘Masterplan ländlicher Raum‘ (2017) <https://www.bmlrt.gv.at/service/publikationen/land/masterplan-laendlicher-raum.html>

Holzinger G, ‘Die Organisation der Verwaltung‘ in Gerhart Holzinger, Peter Oberdorfer and Bernhard Raschauer (eds), Österreichische Verwaltungslehre (Verlag Österreich 2006)

Österreichischer Städtebund, ‘Österreichs Städte in Zahlen‘ (2017) <https://www.kdz.eu/de/content/%C3%B6sterreichs-st%C3%A4dte-zahlen-2017>

Prorok T and others, ‘Struktur, Steuerung und Finanzierung von kommunalen Aufgaben in Stadtregionen‘ (KDZ 2013) <https://www.kdz.eu/de/content/struktur-steuerung-und-finanzierung-von-kommunalen-aufgaben-stadtregionen>

[1] Vienna has different competences because it is at the same time a municipality and one of the nine Länder (Arts 108-112 of the Constitution).

[2] Thomas Prorok and others, ‘Struktur, Steuerung und Finanzierung von kommunalen Aufgaben in Stadtregionen‘ (KDZ 2013) <https://www.kdz.eu/de/content/struktur-steuerung-und-finanzierung-von-kommunalen-aufgaben-stadtregionen> accessed 31 January 2020.

[3] The representation through either one of these associations is constitutionally regulated in Art 115(3) of the Constitution.

[4] Österreichischer Städtebund, ‘Österreichs Städte in Zahlen‘ (2017) 42.

[5] Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Nachhaltigkeit und Wasserwirtschaft, ‘Masterplan ländlicher Raum‘ (BMLFUW 2017).

Local Responsibilities and Public Services in Austria: An Introduction

Alexandra Schantl, KDZ Centre for Public Administration Research Austria

Local governments in Austria perform their own autonomous functions (eigener Wirkungsbereich)[1] as well as tasks delegated by the federation and the respective Land (übertragener Wirkungsbereich). According to Article 116 of the Federal Constitution all municipalities have the same rights and duties (principle of the Einheitsgemeinde) except for the so-called ‘statutory cities’ (Statutarstädte), and Vienna which is both a municipality and a Land.[2]

Local authorities, both urban (ULGs) and rural (RLGs) municipalities, are responsible for a wide range of public services, including the provision of infrastructure, kindergartens, primary schools, retirement homes, etc. As stated by the Federal Constitution they are independent economic entities (Article 116(2) of the Federal Constitution[3]), and as such can contribute to the general economy with running their own industrial and commercial enterprises.

However, depending on the type of service, Austrian municipalities provide public services in different ways. The provision of public services ranges from self-operated municipal companies to public-private partnerships.[4]

Particularly in the last two decades, the municipalities in Austria have increasingly become service providers for citizens rather than being mere administrative authorities. As there is no difference regarding the size or population of municipalities in the Federal Constitutional Law, fulfilling all these local responsibilities can be challenging especially for small Austrian municipalities. Thus, inter-municipal cooperation is a key feature of local government in Austria to provide the necessary economies of scale and expertise that individual municipalities are lacking.[5] Hence, municipal associations (Gemeindeverbände, Article 116(a)) play a crucial role in public service delivery managing, for example water supply or waste management.

Similar to most of the Western European countries ULGs and RLGs in Austria need to tackle different challenges in delivering public services. However, the decrease in public resources together with an increase of public tasks are the main challenges that all Austrian municipalities are facing, due to demographic changes (ageing, migration from rural areas to urban areas), climate change, societal changes (Generation Y, migration and segregation), land take and scarcity, energy transformation and digitization.

Impact of Demographic Changes on the Provision of Local Public Services

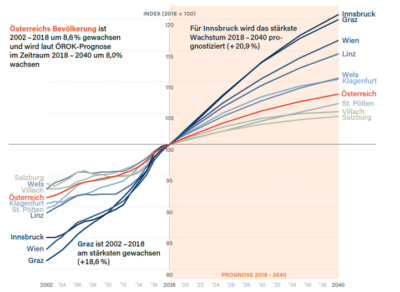

Rural migration and the influx of population into urban areas puts the provision of public services as the central cornerstones of good living conditions under more and more pressure and increases the urban-rural divide. Austria’s population is growing, but there are significant regional differences and many rural regions are affected by population declines. It is the cities and their surrounding regions that are driving population growth in Austria. The population forecast of the Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning (ÖROK) from 2018[6] assumes that the population of Austria will grow by further 710,000 people (+ 8.0 per cent) by 2040. The nine largest cities in Austria – Vienna, Graz, Linz, Salzburg, Innsbruck, Klagenfurt, Villach, Wels and St. Pölten – will account for almost two thirds of the country’s forecast population growth in 2040.

In the past ten years, four out of ten Austrian municipalities have shrunk. The decline affects mainly RLGs in Upper Styria, Upper Carinthia and the northern Waldviertel and Weinviertel in Lower Austria. Most of these RLGs are located far away from economic centers and have poor transport connections.

On the one hand economically week RLGs but also structurally weak ULGs are increasingly losing younger and well-educated people. At the same time, the proportion of elderly people is rising. The population forecast of the Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning (ÖROK) from 2018 believes that in some rural peripheral areas by 2040 more than a third of the population could be over 65 years old. Migration not only changes social life, it also has a negative impact on vacancy and real estate prices, making it more and more difficult to provide services of general interest close to home, and worsens employment and income prospects.

Figure 1: Statistik Austria (POPREG, ÖROK-Prognosis 2018).[7]

On the other hand, economically strong ULGs – especially the capital cities of the Austrian Länder– have benefited from immigration both from other Austrian regions and from abroad and are continuously growing (see figure above). But growth also means a shortage of housing, and public infrastructure is continuously reaching the limits of its capacity and resilience. The boost of commuters together with an unfavorable modal split and the coexistence of people with different ethnic and cultural backgrounds pose further challenges on growing ULGs in Austria.

In order to meet these challenges in both RLGs and ULGs, the promotion of cooperation between municipalities to provide public services in Austria has become a priority on the political agenda. Nonetheless, the approaches for RLGs and ULGs differ. Recognizing the importance of functional areas, ULGs are increasingly trying to develop integrated strategies and projects for territorial cooperation together with their often rural neighboring municipalities. This latest development was driven by the current Austrian spatial development concept (ÖREK 2011) and the partnership ‘Cooperation Platform Urban Regions’, which was mainly supported by the Austrian Association of Cities.[8]

With regards to RLGs, the so-called Master Plan ländlicher Raum in 2017[9] gave a boost to rethinking municipal cooperation as a vital instrument, not only for the better delivering of public services, but also for safeguarding Austria`s rural areas. The Masterplan ländlicher Raum is the result of a broad participation process from autumn 2016 until summer 2017 aimed at sounding out possible solutions for strengthening the rural areas, which was initiated by the then Minister of Agriculture.

Regrettably, the Masterplan ländlicher Raum mainly targets RLGs, and lacks a holistic approach to spatial development. Although the Masterplan ländlicher Raum promotes inter-municipal cooperation as an important implementation tool for the provision of public services, it is not seen as a strategic instrument for integrated territorial development. Paying too less attention to functional areas where ULGs are essential partners for RLGs in delivering public services like public transport hinders a successful urban-rural interplay and contributes to the urban-rural divide.

With the current project of the Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning (ÖROK) on strengthening regional governance including both ULGs and RLGs a first important step towards fostering urban-rural linkages has been set.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Nachhaltigkeit und Wasserwirtschaft, ‘Masterplan ländlicher Raum‘ (2017) <https://www.bmlrt.gv.at/service/publikationen/land/masterplan-laendlicher-raum.html>

Statistik Austria, ´Kleinräumige Bevölkerungsprognose für Österreich 2018 bis 2040 mit einer Projektion bis 2060 und Modellfortschreibung bis 2075 (ÖROK-Prognose)´ (ÖROK 2019) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Bilder/2.Reiter-Raum_u._Region/2.Daten_und_Grundlagen/Bevoelkerungsprognosen/Prognose_2018/Bericht_BevPrognose_2018.pdf>

Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz ÖROK, ´ÖREK-Partnerschaft “Kooperationsplattform Stadtregion“‘ (2011) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/raum-region/oesterreichisches-raumentwicklungskonzept/oerek-2011/oerek-partnerschaften/abgeschlossene-partnerschaften/kooperationsplattform-stadtregion.html>

—— ´Österreichisches Raumentwicklungskonzept ÖREK 2011´ (2011) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/raum/oesterreichisches-raumentwicklungskonzept/oerek-2011>

—— ´Die regionale Handlungsebene stärken – Status, Impulse und Perspektiven´ (publication series no 208, 2020) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/O__ROK_SR_NR._208__2020__Reg_HE_online-Version.pdf>

Österreichischer Städtebund, ´Österreichs Städte in Zahlen 2020´ (2020) <https://www.kdz.eu/de/content/%C3%B6sterreichs-st%C3%A4dte-zahlen-2020>

[1] Own responsibility tasks are local police, markets, traffic facilities, land use planning, social services, water, sanitation and waste, sports and leisure time facilities. In spite of their self-governing status, the municipalities in these respects have to obey Länder and federal laws and are subject to control in legal and efficiency terms. The Länder oversee the budgets of municipalities with reference to economy, profitability, and expediency. The standards of supervision vary considerably between the Länder.

[2] See the Introduction to the System of Local Government in Austria, report section 1.

[3] All municipalities are corporations and have the right to own property, run businesses, levy municipal taxes, and generally manage their own financial affairs: ‘Die Gemeinde ist selbständiger Wirtschaftskörper. Sie hat das Recht, innerhalb der Schranken der allgemeinen Bundes-und Landesgesetze Vermögen aller Art zu besitzen, zu erwerben und darüber zu verfügen, wirtschaftliche Unternehmungen zu betreiben sowie im Rahmen der Finanzverfassung ihren Haushalt selbständig zu führen und Abgaben auszuschreiben.‘

[4] The instruments of public service delivery include: Communal self-supply through enterprises owned and operated by the municipality itself. The Stadtwerke as an organizational part of the municipal administration formed the economic foundation of municipal autonomy. Communal enterprises as independent companies organized under private law. These ‘out-sourced’ communal enterprises do not only deliver public utilities’ services but also increasingly operate cultural or social infrastructures. Communal ordering of services by commissioning private companies. In recent years the ordering of services has got a decisive boost and has replaced the communal enterprise as a means of providing public services in some areas.

Public procurement has become a central instrument for securing public utilities. With the Public service concession, the municipality transfers the right for full or partial provision of public services to a third party. Public Private Partnerships which are used in particular for areas of public utilities that require high infrastructure costs (e.g. hospitals, school campuses, etc.).

[5] For detailed information on inter-municipal cooperation, see report section 4 on local government structure.

[6] Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz ÖROK, ‘Kleinräumige Bevölkerungsprognose für Österreich 2018 bis 2040 mit einer Projektion bis 2060 und Modellfortschreibung bis 2075 (ÖROK-Prognose)‘ (ÖROK 2019) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Bilder/2.Reiter-Raum_u._Region/2.Daten_und_Grundlagen/Bevoelkerungsprognosen/Prognose_2018/Bericht_BevPrognose_2018.pdf> accessed 7 November 2019.

[7] Graph: Ramon Bauer and Tina Frank, ‘Österreichs Städte in Zahlen 2020‘ (Österreichischer Städtebund 2020).

[8] See the Introduction to the Structure of Local Government in Austria, report section 4.1.

[9] Bundesministerium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Nachhaltigkeit und Wasserwirtschaft, ‘Masterplan ländlicher Raum‘ (BMLFUW 2017) <https://www.bmlrt.gv.at/service/publikationen/land/masterplan-laendlicher-raum.html> accessed 6 November 2019.

Local Financial Arrangements in Austria: An Introduction

Robert Blöschl and Dalilah Pichler, KDZ Centre for Public Administration Research Austria

General Structure and Budgeting

In Austria there are three tiers of administration: the federal level (ministries etc), the Länder level and the local level (municipalities, cities). There are nine Länder including Vienna and around 2,100 municipalities. All municipalities manage their own budget independently and can own assets of all kind and operate economic enterprises.

Regarding the municipal financial management, municipalities must prepare an annual budget at the end of the year, which shows in detail which revenues and expenditures are expected for the next year. The local council has to approve the annual budget. In any case, the provision of basic services has to be guaranteed and there are strict regulations on how and for which projects the municipality can take on debts.

Revenues

In Austria there are four main sources of municipal revenue:

- shared tax transfers (around 40 per cent of total operational income);

- local and municipal taxes (around 20 per cent of total operational income);

- fees for municipal services incl. utilities and other educational and social services (around 20 per cent of total operational income);

- current transfers (around 10 per cent of total operational income);

- other fees and income sources (around 10 per cent of total operational income).

Capital transfers for investments are not listed but have been as high as current transfers in the past years as current transfers in absolute values.

A major share of municipal budgets comes from intragovernmental transfers, a complex system of re-distribution of revenues across all levels of government regulated in the Fiscal Equalization Act (Finanzausgleichsgesetz, FAG), which is negotiated every three to eight years between the three levels of administration.[1] This act defines the amount of shared revenues municipalities are granted. One of the main criteria of distribution is the tiered population scheme which reflects changes in population in a nonlinear way. Based on this scheme, urban municipalities with larger populations receive a larger share of the revenues. Shared revenues are mainly comprised of shares out of taxes like the value added tax (VAT), income tax and corporate tax. In total around 15 per cent of shared revenues are allocated to municipalities in the context of fiscal equalization.[2] Shared taxes amounted to EUR 6.7 billion in 2018 for the local governments (without the Capital City of Vienna).[3]

In addition to shared revenues, local taxes are an important factor of municipal income. The most important local tax for municipalities’ budgets is the ‘municipality tax’. Companies based in Austria have to pay municipality tax amounting to 3 per cent of the total sum of salaries paid within one month. Therefore, municipalities with higher employment have higher municipality tax income. In general, this applies stronger to urban local governments (ULGs) and municipalities with a strong tourism industry. Property tax is levied on individuals owning property, the amount is set by the municipalities considering a legal tax cap. As there has not been a reform since 1973, the property tax is currently under revision and likely to be reformed in the next years.[4] Municipality tax amounted to about EUR 2.5 billion in 2018 whereas property tax amounted to about EUR 600 million (all municipalities except Vienna).[5]

Besides shared revenues there is a further intragovernmental transfer system between municipalities and the federal and Länder level. Each Land determines a levy that all municipalities must transfer, e.g. in order to finance the hospitals run by the Länder. In return, the Länder and also the national government distribute transfers to support municipal investments. These transfers can be divided into current transfers and capital transfers. Current transfers are meant to finance the maintaining of public services. Capital transfers however are purposed to allow for investments in infrastructure for example. Current transfers amounted to EUR 1.6 billion in 2018 with current transfers from the federal level amounting to 20 per cent and from the Länder level to 60 per cent. Municipalities that are not able to break even their budgets (e.g. because of losses in municipality tax revenue or structural issues) are granted additional transfers from the Länder to cover the deficit. However, all further investments are subject to approval by the Länder level, who monitors the municipality until a sustainable and balanced budget is reached. Through this transfer system, rural local governments (RLGs) benefit stronger as levies are higher for municipalities with more income.

Fees are mainly generated through the provision of public services and utilities such as water, sewerage and waste. There are, however, local authority associations that carry out these services and have their own budget. In this case municipalities make proportionate payments to cover the costs of the associations.

To conclude, important expenditure-incurring tasks such as health care and social protection happen at subnational level, but a minor share is financed through municipal revenues. As a result, municipalities are financially dependent mainly on the shared tax transfers (Ertragsanteile) by higher levels of government due to the significant mismatch between revenue raising power and expenditure responsibilities.[6] While the shared tax transfers and local tax incomes are higher in ULGs, after the mandatory transfer (levies, current and capital transfers) the income of RLGs becomes more level with that of urban ones.

Public Spending and Debt

Municipalities cover a wide arrange of tasks from the construction and maintenance of streets to kindergartens, primary schools, residential care homes for elderly people and services like water supply, sewerage and waste disposal.[7] Highest expenditures are carried out in the fields of services (e.g. water, sewerage, waste), welfare and education.[8] Expenditure has to follow the approved budget. If deviations from the budget occur (e.g. because of unforeseen projects) municipalities have to prepare a revised budget and gain the approval of the local council.

In general, municipalities are only allowed to take on long-term debt for capital spending. Current expenditures cannot be covered with long-term debt. There are rules for short-term loans which have to be paid back within the fiscal year. Furthermore, Länder law prohibits the use of risky financial instruments. Over the last ten years municipal debt slightly rose from EUR 11.5 billion in 2009 to 11.6 billion in 2018.[9]

Recent Developments

Until 2019 Austrian municipalities followed the rules of a cameralistic system. The budgeting and accounting were done according to a cash-flow oriented system. From 2020 on an accrual system is now implemented. The income statement shows the resource flows within the municipality. The cash flow statement shows the cash inflows and outflows. The balance sheet includes balances of assets, accounts receivable, accounts payable, loans etc. With this shift to a more resource-oriented concept a holistic assessment of municipal accounting is possible.[10]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Blöschl R, Hödl C and Maimer A, ‘Mit der VRV 2015 zu mehr Generationengerechtigkeit‘ in Peter Biwald and others (eds), Nachhaltig wirken. Impulse für den öffentlichen Sektor (NWV 2019)

Bröthaler J, Haindl A and Mitterer K, ‘Funktionsweisen und finanzielle Entwicklungen im Finanzausgleichssystem‘ in Helfried Bauer and others (eds), Finanzausgleich 2017: Ein Handbuch (NWV 2017)

European Commission, ‘Country Report Austria 2019’ COM (2019) 150 final.

Geißler R and Ebinger F, ‘Austria’ in René Geißler, Gerhard Hammerschmid and Christian Raffer (eds), Local Public Finance in Europe. Country Reports (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2019)

Mühlberger P and Ott S, Die Kommunen im Finanz- und Steuerrecht (1st edn, DBV 2016)

Österreichischer Städtebund (ed), ‘Stadtdialog. Schriftenreihe des Österreichischen Städtebundes, Gemeindefinanzen 2020 – Entwicklungen 2009 – 2023‘ (forthcoming)

[1] See Johann Bröthaler, Anita Haindl and Karoline Mitterer, ‘Funktionsweisen und finanzielle Entwicklungen im Finanzausgleichssystem‘ in Helfried Bauer and others (eds), Finanzausgleich 2017: Ein Handbuch (NWV 2017).

[2] ibid.

[3] See Österreichischer Städtebund (ed), ‘Stadtdialog. Schriftenreihe des Österreichischen Städtebundes, Gemeindefinanzen 2020 – Entwicklungen 2009 – 2023‘ (forthcoming).

[4] See Peter Mühlberger and Siegfried Ott, Die Kommunen im Finanz- und Steuerrecht (1st edn, DBV 2016); René Geißler and Falk Ebinger, ‘Austria’ in René Geißler, Gerhard Hammerschmid and Christian Raffer (eds), Local Public Finance in Europe. Country Reports (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2019).

[5] See Österreichischer Städtebund, ‘Stadtdialog‘, above.

[6] European Commission, ‘Country Report Austria 2019’ COM (2019) 150 final.

[7] See Geißler and Ebinger, ‘Austria’, above.

[8] See Österreichischer Städtebund, ‘Stadtdialog‘, above.

[9] ibid.

[10] See Robert Blöschl, Clemens Hödl and Alexander Maimer, ‘Mit der VRV 2015 zu mehr Generationen-gerechtigkeit‘ in Peter Biwald and others (eds), Nachhaltig wirken. Impulse für den öffentlichen Sektor (NWV 2019).

The Structure of Local Government in Austria: An Introduction

Alexandra Schantl, KDZ Centre for Public Administration Research Austria

Like in many other European countries, the first efforts to merge municipalities in Austria started in the 1960s. While the municipal structures in the western Länder of Austria (Vorarlberg, Tirol, Salzburg and Upper-Austria) were already organized in larger units, Lower Austria, Burgenland, Styria and, to some extent Carinthia, were characterized by small-scale municipalities.

Thus, in Lower Austria the number of municipalities decreased from 1,652 municipalities in the year 1965 to 573 municipalities as of now. In Burgenland the amalgamation process started in 1971 by merging the 319 municipalities into 138. Due to later municipal separations, the number of today is 171. With the municipal structural reform in Carinthia in 1973 the number of municipalities was reduced from 242 to 121 municipalities. Again due to some later municipal separations Carinthia today has 132 municipalities. The most recent municipal structural reform in Austria took place from 2010 to 2015 in Styria. The number of municipalities decreased from 542 to 287. This reform also affected the Styrian districts by reducing their number from 17 to 13.

Similar to Switzerland, amalgamations in Austria are driven either by the municipalities themselves (bottom-up) or by the Länder (top-down). The process of the most recent structural reform in Styria was driven by the Land. Accompanying measures, direct involvement of the affected municipalities through participation and financial incentives were intended to ensure that the amalgamations of municipalities proposed by the Land were voluntary. Due to strong resistance of numerous municipalities, the structural reform needed in the end both voluntary and coercive mergers.

However, from the current 2,100 municipalities in Austria only about 70 municipalities have a population of more than 10,000 inhabitants. From the 8.8 million inhabitants in Austria one third of the population lives in the metropolitan area of Vienna.[1] Hence, Austria has a very fragmented and small-structured municipal landscape.

One reason for the reluctance to territorial reforms in Austria is the clear preference for inter-municipal cooperation. While there is no political program for amalgamations in Austria, the federal government, the Länder and the local government associations support the further development of inter-municipal cooperation.

Since 2011 the constitutional law to strengthen the powers of municipalities[2] significantly enlarges the rights of municipalities to establish inter-municipal associations, even across Länder borders, primarily to increase service efficiency not only in their own competences, but also in transferred competences. Its implementation was accelerated as a result of the financial crisis and existing budget restrictions aimed to reduce costs by a reorganization of local public services and a new way of managing local and regional authorities’ payrolls. Moreover, Länder programs to encourage local authorities to modernize their services and to use innovative approaches have been also introduced. Currently all Länder provide incentives for inter-municipal cooperation, some of them even tie their transfer payments (in the financial equalization) to municipalities to inter-municipal cooperation. And the present program of the federal government (2020-2024)[3] promotes to abolish the VAT for inter-municipal cooperation to facilitate co-operations and make them more attractive.

Inter-municipal cooperation in Austria has a long tradition and is based on the principle of voluntariness. Nonetheless, the cooperativeness of municipalities is still rather weak. The often long and resource intensive initiation processes, interest conflicts or only the reluctance to give up own structures for joint projects still hinders inter-municipal cooperation.

In general, all municipal tasks or services in Austria, with the legal competence being anchored in the Federal Constitution, can be carried out inter-municipally. Limitations apply only to the legal form of cooperation: e.g. governing powers cannot be carried out by a private company (municipal housing inspectorate, municipal registry of births, marriages and deaths, municipal taxes etc.).

The main inter-municipal cooperation fields in Austria are:

- supply and disposal (e.g. water and waste);

- regional development and tourism;

- sports and leisure infrastructure (public swimming pools, sport halls, event centers etc.)

- social services (social welfare associations, retirement homes etc.);

- education (kinder garden, elementary and middle schools, residential accommodation for pupils);

- particular governing powers areas (municipal housing inspectorate, municipal registry of births, marriages and deaths etc.);

- internal administrative services like procurement, accounting etc.

In the past decade, inter-municipal cooperation in location development (business parks, business location etc.) has become more and more important, while fire-services cooperation is still very limited.

Support for inter-municipal cooperation differs from one Land to another Land in terms of both financial means and non-monetary services. Normally the establishment and management of inter-municipal cooperation are funded by the Länder, while cooperation itself or investments are usually not subsidized.

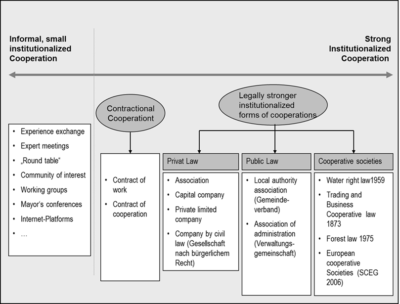

The form of cooperation depends on the tasks and duties. It ranges from informal and non- or little institutionalized cooperation to strong and highly institutionalized cooperation. For certain municipal tasks, the legal form of local authority association (Gemeindeverbände) is mandatory. [4] Scope and tasks are defined by the laws of the Austrian Länder.

Figure 7: Forms of Cooperation in Austria.[5]

Figure 7: Forms of Cooperation in Austria.[5]

Inter-municipal cooperation in the framework of an association is possible for a wide range of cooperations, except for governing power services and for profit.

The administrative association can be seen as the typical model for inter-municipal cooperation, since only municipalities can cooperate in this legal form. Involvement of other legal partners is unlawful. It can be used for either specific services or for all municipal services. The administrative association is neither a public corporation nor a commercial company and therefore not liable for corporation tax unless the association provides private services of general interest, which then will be subject to VAT (value added tax).

The local authority association (Gemeindeverband) is a public corporation and is laid down in the Constitution (Article 116(a)).[6] They are led by elected bodies, in general by the mayor of one member municipality. There is no limitation of the purpose. Since 2011 and as already mentioned before, cross-border municipal cooperation between the Austrian Länder, as well as multi-purpose municipal cooperation are possible. Unlike administrative associations, the local authority takes over the services of the member municipalities as a separate body and with its own responsibilities. It is particularly suitable for tasks that require high investments or for politically sensitive areas. Setting up a municipal corporation is no more difficult than setting up a private company.

Involving private partners, the limited liability company (GesmbH) is the most common legal form in Austria for inter-municipal cooperation.

Cooperative societies (Genossenschaften) have a long tradition in Austria, but only in the field of housing, water supply, and forestry. This legal form has not yet been used for inter-municipal cooperation in Austria.

The federal level in Austria cannot interfere in local government structures since local self-government is safeguarded by the Constitution (Article 116ff). Nevertheless, with the Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning (ÖROK)[7], founded in 1971 and established by the federal government, the Länder and the municipalities spatial development is coordinated at the national level. Thus, the ÖROK plays a crucial role in promoting and developing structural reform approaches.[8] In this context urban regions (Stadtregionen) in Austria have gained importance and relevance over the last decade through certain ÖROK initiatives: the current Austrian Spatial Development Concept (ÖREK 2011)[9] and the partnership ‘Cooperation Platform Urban Regions’[10] with the recommendation ‘For an Austrian Policy for Urban Regions’[11] and the roadmap for implementing the ‘Austrian Agenda Urban Regions’[12] not only successfully established the topic in the public discussion but also gave a boost to the development of urban regions in Austria. A crucial role in promoting urban regions in Austria is played by the Austrian Association of Cities and Towns which not only had the lead of the before mentioned partnership ‘Cooperation Platform Urban Regions’ but also established the ‘Annual Forum of Austrian Urban Regions’[13] and the platform <www.stadtregionen.at> for active urban regions in Austria in terms of joint planning and implementation. Nevertheless, urban region initiatives often depend on the pioneering spirit and commitment of single stakeholders since they are commonly formalized only by inter-municipal agreements with a low degree of institutionalization.

Finding viable solutions for integrated and sustainable regional development both for urban local governments (ULGs) and rural local governments (RLGs) cooperation without introducing new levels of government has been the objective of the current ÖROK project ‘Strengthening regional governance’. The project results (status quo, impulses and perspectives) are summarized in the ÖROK study ‘Die regionale Handlungsebene stärken: Status, Impulse & Perspektiven’.[14]

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Council of European Municipalities and Regions, ‘Decentralisation at a Crossroads. Territorial Reforms in Europe in Times of Crisis’ (CEMR 2013) <https://www.ccre.org/img/uploads/piecesjointe/filename/CCRE_broch_EN_complete_low.pdf>

Ebinger F, Kuhlmann S and Bogumil J, Territorial Reforms in Europe: Effects on Administrative Performance and Democratic Participation (Informa UK Limited 2018) <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03003930.2018.1530660?needAccess=true>

Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe, ‘Local and Regional Democracy in Austria. Monitoring Report’ (CG(20)8, 3 March 2011) <https://rm.coe.int/090000168071aca8#_Toc287373831>

Pitlik H, Wirth K and Lehner B, Gemeindestruktur und Gemeindekooperation (WIFO and KDZ 2010) <http://www.wifo.ac.at/wwa/pubid/41359>

Wirth K and Biwald P, ‘Gemeindekooperationen in Österreich. Zwischen Tradition und Aufbruch‘ in Peter Biwald, Hans Hack and Klaus Wirth (eds), Interkommunale Kooperation. Zwischen Tradition und Aufbruch (NWV 2006)

[1] KDZ, ‘Stadtregion Wien’ (stadtregionen.at, 2019) <https://www.stadtregionen.at/wien> accessed 11 November 2019.

[2] See 60. Bundesverfassungsgesetz: Änderung des Bundes-Verfassungsgesetzes zur Stärkung der Rechte der Gemeinden [Federal Constitutional Law on the Strengthening of the Rights of Municipalities], GP XXIV GABR 1213 AB 1313 S. 112. BR: AB 8526 S. 799.).

[3] See ‘Aus Verantwortung für Österreich. Regierungsprogramm 2020–2024’ (Bundeskanzleramt Österreich 2020) 11.

[4] Cases where cooperation may be imposed by the legislation concern, for example, waste-management associations.

[5] See Klaus Wirth and Markus Matschek, ‘Interkommunale Zusammenarbeit. Möglichkeiten, Grenzen und aktueller Entwicklungsbedarf‘ (2005) 71 ÖGZ 8.

[6] The Federal Constitutional Law (Art 116(a)) provides that municipalities may join together – by agreement or by law – to form ‘Local Authority Associations’ (Gemeindeverbände) to deal with common specific matters within their own sphere of competences. The Local Authority Association may be voluntary as well as mandatory. In the first case the approval of the supervisory authority is necessary. This approval must be given under certain conditions specified in the Federal Constitutional Law.

[7] See Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz ÖROK, ‘Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning. ÖROK‘ (ÖROK, 2020) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/english-summary/> accessed 11 November 2019.

[8] The current ÖROK project ‘Fostering Regional Governance’ aims at sounding out new approaches for strengthening sustainable integrated development in functional areas.

[9] See Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz ÖROK, ‘Österreichisches Raumentwicklungskonzept OREK 2011‘ (ÖROK, 2020) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/?id=224> accessed 2 August 2019.

[10] See Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz ÖROK, ‘OREK-Partnerschaft “Kooperationsplattform Stadtregion“‘ (ÖROK, 2020) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/raum-region/oesterreichisches-raumentwicklungskonzept/oerek-2011/oerek-partnerschaften/abgeschlossene-partnerschaften/kooperationsplattform-stadtregion.html> accessed 2 August 2019.

[11] See Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz ÖROK, ‘ÖROK-Empfehlung Nr. 55 “Für eine Stadtregionspolitik in Österreich”’ (2017) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/fileadmin/Bilder/2.Reiter-Raum_u._Region/5.Empfehlungen/OEROK-Empfehlung_Nr._55_angenommen_HP.pdf> accessed 2 August 2019.

[12] See Österreichisches Raumentwicklungskonzept ÖREK, ‘Roadmap zur Umsetzung der “Agenda Stadtregionen in Österreich“‘ (ÖREK 2017) <https://www.stadtregionen.at/uploads/files/RoadmapAgendaStadtregionen_FINAL.pdf> accessed 2 August 2019.

[13] See ‘6. Österreichischer Stadtregionstag 2018 in Wels‘ (Österreichischer Städtebund, 10 October 2018) <https://www.staedtebund.gv.at/services/veranstaltungsergebnisse/veranstaltungsergebnisse-details/artikel/6-oesterreichischer-stadtregionstag-2018-in-wels/> accessed 2 August 2019.

[14] Österreichische Raumordnungskonferenz (ÖROK), ´Die regionale Handlungsebene stärken – Status, Impulse und Perspektiven´ (paper series no 208, ÖROK 2020) <https://www.oerok.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/O__ROK_SR_NR._208__2020__Reg_HE_online-Version.pdf>.

Intergovernmental Relations of Local Governments in Austria: An Introduction

Karoline Mitterer and Dalilah Pichler, KDZ Centre for Public Administration Research Austria

The responsibility of providing public services in most areas, such as education, health, elderly care or transport, is shared among all three levels of government. The intertwinement of public service provision and financial flows, however, is often considered complex. For a long time, a more transparent distribution of competences between all levels of government as well as organizational and financial disentanglement of public service provision is being discussed. Nevertheless, these reforms are only being implemented reluctantly, due to given constitutional federal structures. [1] [2]

Coordination Between the National Government and the Länder

When jointly providing public services the need for coordination and coherent actions between levels of government is considerable. Traditionally, the allocation of responsibilities is specified in agreements under private law or in the framework of simple legal regulations. To meet centralistic requirements and decentral preferences, the Constitution (Article 15(a))[3] provides the possibility for the national government and the Länder governments to enter into agreements on specified policy fields, for example in health policy[4] or elementary education.[5]

Coordination Between all Three Levels of Government

Another example is the Pact on the Fiscal Equalization,[6] which is agreed upon between national government, Länder and municipalities for a time period of four to six years. In this pact the financial flows between the levels of government are settled. This affects among other tasks the rights of taxation, the distribution of revenues from the shared federal taxes and who bears specific costs. The Pact on the Fiscal Equalization has proven to be a central element for securing the financial autonomy of all government levels, due to the fact that all stakeholders have to agree to the pact. In this process the local level also has a strong role and is represented by the two local government associations (LGAs), the Austrian Association of Municipalities (Österreichischer Gemeindebund) for smaller rural municipalities, and the Austrian Association of Cities and Towns (Österreichischer Städtebund), for middle-sized to larger cities. Ideally both associations have a joint position during the negotiations with the national and Länder-level. However, there are topics where a balance of interests for all sizes of municipalities is not sufficiently met, which weakens the negotiation position of the local level as a whole in this process.

Coordination Between Länder and Municipalities

Diverse intergovernmental relationships exist between the Länder and their respective municipalities. These include Länder-specific regulations for providing and financing public services, complex financial transfers, deployment of human resources for different services and organizational regulations. Regulation for cooperation strategies and instruments between the two levels are not common. The 2018 Regional Development Act of the Land of Styria[7] is however a recent attempt for a strategic orientation regarding regional development between the Land, the Styrian regions and their municipalities. Furthermore, the act stipulates tasks, instruments as well as joint distribution of resources for the development of regions.[8] Other examples relate to reforms enforcing more cooperation on subnational level through outsourcing of organizational units as independent legal entities, regional funds, or the establishment of funds for joint service provision and financing like hospital districts in some Länder or the social fund in the Land of Vorarlberg.[9]

The potential trade-off between cooperation and supervision is especially relevant for municipalities and their respective Länder, as the Länder governments are responsible for municipal supervision regarding local finances. Recent developments show that the Länder do not predominantly exercise control through this role, but strongly see themselves in a consulting position as well. Länder can also influence investments and infrastructure projects of the local level, as they manage cost contributions, financial transfers and grants for such ventures. This poses a discrepancy to the constitutional right to self-government of the municipalities, which is partly limited through the previously stated operational and financial intertwinement with the Länder. Therefore, there are calls for reducing these interdependencies.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Bauer H and Biwald P, ‘Governance im österreichischen Bundesstaat voranbringen‘ in Helfried Bauer, Peter Biwald and Karoline Mitterer (eds), Governance-Perspektiven in Österreichs Föderalismus. Herausforderungen und Optionen (NWV 2019)

Federal Ministry of Finance, ‘Paktum zum Finanzausgleich 2017’ (2017) <https://www.bmf.gv.at/themen/budget/finanzbeziehungen-laender-gemeinden/paktum-finanzausgleich-ab-2017.html>

Thöni E and Bauer H, ‘Föderalismusreformen oder Gamsbartföderalismus in Österreich?‘ in Peter Biwald and others (eds) Nachhaltig wirken. Impulse für den öffentlichen Sektor (NWV 2019)

[1] An OECD study categorizes Austria as a state with centralized fiscal structures, which ‘tends to combine low autonomy and responsibility with a high level of co-determination and strong fiscal rules and frameworks’ for subnational governments. See Hansjörg Blöchliger and Jaroslaw Kantorowicz, ‘Fiscal Constitutions: An Empirical Assessment’ (2015) 1248 OECD Economics Department Working Papers <https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrxjctrxp8r-en> 5.

[2] See Helfried Bauer and Peter Biwald, ‘Governance im österreichischen Bundesstaat voranbringen‘ in Helfried Bauer, Peter Biwald and Karoline Mitterer (eds), Governance-Perspektiven in Österreichs Föderalismus. Herausforderungen und Optionen (NWV 2019); Erich Thöni and Helfried Bauer, ‘Föderalismusreformen oder Gamsbartföderalismus in Österreich?‘ in Peter Biwald and others (eds) Nachhaltig wirken. Impulse für den öffentlichen Sektor (NWV 2019).

[3] Art 15(a) agreements are guaranteed by the Constitution and were made possible in 2004 through a constitutional reform.

[4] Federal Ministry of Finance, ‘Zielsteuerung Gesundheit‘ <https://www.bmf.gv.at/themen/budget/finanzbeziehungen-laender-gemeinden/paktum-finanzausgleich-ab-2017.html> accessed 21 February 2020.

[5] Agreement on Elementary Education for the Years 2018/19 to 2021/22, BGBl. I no 103/2018.

[6] Federal Ministry of Finance, ‘Paktum zum Finanzausgleich 2017‘ <https://www.bmf.gv.at/themen/budget/finanzbeziehungen-laender-gemeinden/paktum-finanzausgleich-ab-2017.html> accessed 21 February 2020.

[7] Styrian Spatial and Regional Development Act (Steiermärkisches Landes- und Regionalentwicklungsgesetz), LGBl. no 117/2017.

[8] Bauer and Biwald, ‘Governance im österreichischen Bundesstaat voranbringen‘, above.

[9] ibid.

People’s Participation in Local Decision-Making in Austria: An Introduction

Dalilah Pichler, KDZ Centre for Public Administration Research Austria

The concept of people’s participation in a representative democracy has many different layers. It can range from an informative character, to public consultations, and can go as far as co-decision-making or co-production. In Austria, traditional instruments of direct democracy are of high relevance, as they are embedded in the Austrian Constitution, namely the referendum, the popular initiative and the public consultation. These instruments are primarily set out for the two legislative authorities on federal and Länder level.[1] However, the Constitution also enables Länder legislation to stipulate possibilities of direct participation and involvement on municipal level, but only in matters within the municipality’s own sphere of influence and reserved for citizens who are entitled to elect the municipal council. Following this proposal, all Länder have in different scopes embedded possibilities of local plebiscites in their legislations, which vary between the Länder. The main differences are of procedural nature and of how the requirements are set for the initiation of such instruments. The referendum for example is typically intended for resolutions of the local council, however citizens do not always have the possibility to enforce it. The popular initiative can be initiated in all Länder and in statutory cities, however not in all municipalities, depending on the provincial legislation.[2]

Idealistically, the citizens of a municipality are given the right for self-governance, but the law curtails this right of direct democracy in certain topics on the local level such as questions on budget, personnel, elections, fees and taxes etc.[3] Public consultation is the most wide-spread and used instrument of direct democracy in Austrian municipalities.[4] Also transparency rules and information processes for the public in municipal governments are embedded in legislation of most of the Länder.

Nevertheless, the legislative instruments reach to the rungs of information and consultation in the participation ladder. There is no obligation of councils or other legislative authorities to adhere to the outcome of public consultations or popular initiatives. A change would require a constitutional revision, as representative democracy cannot be overruled by such initiatives. This does not mean that the ‘softer forms’ of participation are not present. There have been efforts in some Länder to install ‘citizen councils’ of randomly chosen citizens who are representative of the population to enhance deliberation of specific political topics. These ‘citizen councils’ formulate a joint statement that serves as a suggestion for further debate and political decision-makers can derive measures from the outcome of these discussions.[5] The inclusion of multiple stakeholders in planning and/or decision-making processes can also be found, often in the context of improving quality of life in a municipality. This is particularly reflected in the Lokale Agenda 21 (LA 21) processes, based on the UN Agenda 21 action plan to which both national and Länder governments have committed to. With facilitation of their Länder, municipalities can implement different participative formats within the LA 21 process for creating a vision for the local community, the setting of common goals and strengthening cooperation between citizens, administration and politicians.

New and innovative forms of peoples’ participation have yet to come into practice. Major restrictions in the current system of municipal direct democracy are taboo topics for plebiscites and a high threshold for starting a participatory process, politicization and targeted use of such instruments for agenda setting, and the perception of participatory instruments for deliberation rather than decision-making.[6] This means that participatory mechanisms are initiated and rather driven by political parties, rather than citizen being able to actively influence public policies. Especially the referendum, where the outcome is legally binding for representatives, is rarely used although there is a general interest of the population to be more involved in direct democratic procedures.[7] However, the softer and less regulated forms of participation pave the way for more deliberation in the public sphere. Local governments can obtain valuable knowledge and gather ideas for certain topics, if they provide an adequate framework for the participants.

References to Scientific and Non-Scientific Publications

Balthasar A, ‘Die Europäische Bürgerinitiative und andere Instrumente der direkten Demokratie in Europa‘ in Peter Bußjäger, Alexander Balthasar and Niklas Sonntag (eds), Direkte Demokratie im Diskurs (New Academic Press 2014)

Gamper A, ‘Partizipation und Bürgerbeteiligung in Österreichs Städten‘ in Österreichischer Städtebund (ed), Österreichs Städte in Zahlen (2015)

Haller M and Feistritzer G, ‘Direkte Demokratie in Österreich. Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage‘ in Peter Bußjäger, Alexander Balthasar and Niklas Sonntag (eds), Direkte Demokratie im Diskurs (New Academic Press 2014)

Hellrigl M, ‘Bürgerräte in Vorarlberg‘ in Peter Bußjäger, Alexander Balthasar and Niklas Sonntag (eds), Direkte Demokratie im Diskurs (New Academic Press 2014)

Pleschberger W, ‘Kommunale direkte Demokratie in Österreich – Strukturelle und prozedurale Probleme und Reformvorschläge‘ in Theo Öhlinger and Klaus Poier (eds), Direkte Demokratie und Parlamentarismus (Böhlau Verlag 2015)

Prorok T, ‘Beteiligung von BürgerInnen in Zeiten von Open Government‘ in Thomas Prorok and Bernhard Krabina (eds), Offene Stadt (NWV 2012)

[1] Alexander Balthasar, ‘Die Europäische Bürgerinitiative und andere Instrumente der direkten Demokratie in Europa‘ in Peter Bußjäger, Alexander Balthasar and Niklas Sonntag (eds), Direkte Demokratie im Diskurs (New Academic Press 2014).

[2] Anna Gamper, ‘Partizipation und Bürgerbeteiligung in Österreichs Städten‘ in Österreichischer Städtebund (ed), Österreichs Städte in Zahlen (2015).

[3] Werner Pleschberger, ‘Kommunale direkte Demokratie in Österreich – Strukturelle und prozedurale Probleme und Reformvorschläge‘ in Theo Öhlinger and Klaus Poier (eds), Direkte Demokratie und Parlamentarismus (Böhlau Verlag 2015).

[4] Thomas Prorok, ‘Beteiligung von BürgerInnen in Zeiten von Open Government‘ in Thomas Prorok and Bernhard Krabina (eds), Offene Stadt (NWV 2012).

[5] Manfred Hellrigl, ‘Bürgerräte in Vorarlberg‘ in Peter Bußjäger, Alexander Balthasar and Niklas Sonntag (eds), Direkte Demokratie im Diskurs (New Academic Press 2014).

[6] Pleschberger, ‘Kommunale direkte Demokratie in Österreich’, above.

[7] Max Haller and Gert Feistritzer, ‘Direkte Demokratie in Österreich. Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage‘ in Peter Bußjäger, Alexander Balthasar and Niklas Sonntag (eds), Direkte Demokratie im Diskurs (New Academic Press 2014).